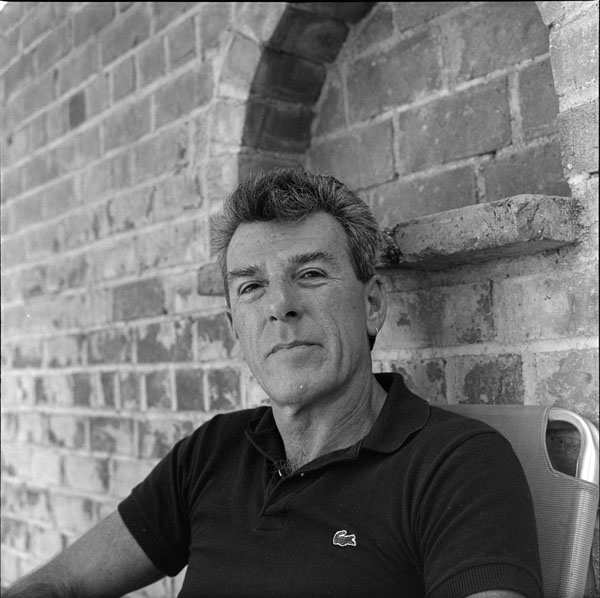

Thom Gunn, 1986. Photograph by LaVerne Harrell Clark.

Courtesy of The University of Arizona Poetry Center. Copyright Arizona Board of Regents

Andre Bagoo

Thom Gunn’s poem ‘The Messenger’ starts with a question:

Is this man turning angel as he stares

At one red flower whose name he does not know,

The velvet face, the black-tipped hairs?

The question tells us what to see: a man, an angel, a flower. Think of a Renaissance painting with an angel, no doubt bearing some prophetic message, in front of a window or at the bottom of a shaft of light, bowing to a figure for whom he has been summoned. Here, the angel looks at a flower. But the flower has features that beg more questions. What to make of its redness, its velvety texture, its black hair? Suddenly the scene is no longer a quaint picture. As if confirming suspicion, the sensual rises. We leap:

His eyes dilated like a cat at night,

His lips move somewhat but he does not speak

Of what completes him through his sight.

Whose eyes? The angel looking down? Or the man looking back up? Whose lips? What are the lips doing? We no longer see a solitary person with a plant. We no longer know who is above and who is below. Instead, two figures are changing roles, and one man is on his knees. The phrase “what completes” is threefold: a fantasy fulfilled, a full insertion, a full climax: “His body makes to imitate the flower / Kneeling, with splayed toes pushing at the spoil.” The flower is phallic. The prayer, fellatio.

Contraries gush in Thom Gunn’s poems. ‘The Messenger’ is an example of one end of the spectrum. Openly gay, he could be explicit in his writing. But here, the reader is asked to fill in the blanks. The result is something that is, paradoxically, more vivid. As Baudelaire said: “That which is created by the mind lives more truly than matter.”

We live in an era when queer voices are required to wear their politics on their sleeve. At the same time, straight voices are not. They are never accused of masking their sexuality in their verse. Mystery is their prerogative not ours. Gunn’s understated approach might be dismissed as outmoded, apologetic, a form of hiding. But while visibility is undoubtedly powerful, it’s a mistake to dismiss him when he writes in this mode. As anyone who has seen Robert Mapplethorpe’s flowers knows, less is more.

The month of August marks 90 years since Gunn’s birth. He was born in Kent, England, on August 29, 1929, and died in San Francisco on April 25, 2004. His father, Herbert, was a newspaper editor. His mother, Charlotte, a former journalist who wrote poetry. She killed herself when Thom was 15. He was among those who discovered her body. In adult life, he kept a picture of her, holding him as a baby, over his writing desk. He never escaped her embrace. The biggest risk factor for suicide is a relative who did the same. Though much water had passed under the bridge by the time of his death, at the age of 74 from “acute polysubstance abuse”, it is not hard to see a link between Gunn’s adulthood and the trauma of his mother’s death.

Just as we can see patterns in the poet’s life, so too can we find them in the poetry. Over the course of several books, there is a movement from poems, such as ‘The Messenger’, in which sex is suggested and those in which sex is handled plainly. There is also a movement from closed forms to a more relaxed line. Though there is something to be said for The Death of the Author, these dynamics were undeniably shaped by aspects of Gunn’s life.

Gunn was not close to his father. His mother’s death deprived him of an important source of parental approval. At Stanford, he was taught by Yvor Winters. In Winters, who emphasised rigor and discipline, Gunn found a surrogate. But in the process he also cultivated a new fear. Would this surrogate accept his sexuality? (In 1995, Gunn told The Paris Review Winters “would have been appalled at the idea that I was queer.”)

Gunn’s traditional forms were a way of pleasing his teacher. In studding the early books with rhyming couplets, carefully calibrated meters, sonnets, and other controlled devices, the poet was vying for acceptance from a parental figure. He was also vying for acceptance from the world at large, a world in which English Letters is still not seen as gay-friendly despite a long tradition of queer poets and writers. If the later books tended to have more free verse, more syllabic verse, more prose poetry, this was a reflection of the poet’s increasing confidence. Or, viewed another way, his diminished concern.

The earlier forms performed another function. They gave Gunn a sense of closing Pandora’s box, of sealing the terrain of unruly emotion. Winters’ ideal of discipline could be a way to keep self-destructive forces at bay by imposing order on language. Gunn was HIV negative, but the devastating effects of HIV/AIDS surrounded him. Despite this, his sexual compulsions never dimmed, even into his 60s and 70s. Nor, it seems, his risk-taking. His partner, Mike Kitay, remarked: “It seemed to me something besides libido. There’s something there that’s bottomless, that no amount can fill up.”

If you look closely you see another transformation. As the years pass, more of them spring from the soil of Gunn’s words. Flowers. Foxgloves, lilies, lilacs, poppies, tulips, morning glories. The red flower of ‘The Messenger’ is just one example. There’s a vitality and celebration, even if tempered by the somberness of work that deals with death.

“Rebellion,” Gunn wrote in The Passages of Joy, “comes dressed in conformity”. He may have been looking for acceptance in his poetry, but he was also doing the opposite. Just as St Lucian poet Derek Walcott co-opted traditional forms to send a message back to the colonial motherland, so too did Gunn deploy strictures to make a point. In his poetry Gunn says as a gay man: Look I can do this too, just like any of you. He also says: Look, let us laugh at the quaintness of this masquerade together. In such carnivalesque contrariness lies a sophisticated queerness that is sometimes not fully appreciated. It’s a radical inside job.