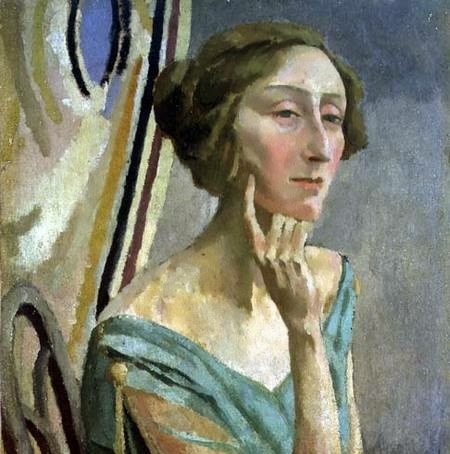

Portrait of Edith Sitwell by Roger Fry, 1915

Mark Valentine

The copy of The Wooden Pegasus (1920) by Edith Sitwell that I have is discarded from Sheffield City Library. There is a typed sticker on the front free endpaper saying she is the daughter of Sir George Reresby Sitwell of (nearby) Renishaw Hall, presumably meant to appeal to local interest (or snobbery). She was 33 when it was published. The note does add ‘Poet and critic’.

Mysteriously another sticker, to the outside, proved when removed to contain on the back the words PEACH/Any old iron, which might come from a surrealist poem. The allusion is probably not to the popular music hall song, but to a play of that name by L Garde du Peach. It has become associated with the Sitwell volume by some chance adhesion. But it is not entirely far from the poet’s own freewheeling and frolicking use of vivid words. Nor does the incidental delight of the book end there.

For on the verso of the second front free endpaper is a framed box advertising two titles ‘By the Same Author’. One is her anthology of contemporary avant-garde verse, Wheels, here with a notice from The Saturday Review acclaiming it ‘The vanguard of British Poetry’, which it certainly was. The other is her earlier book of poems Clowns Houses (1918). This amusingly cites only one press notice about it, from Land and Water, originally a sporting and country life magazine but at that time edited by Hilaire Belloc: ‘It affects me like devilled almonds.’ That is the complete encomium. Presumably it was meant at least half-approvingly, and the poet quotes it with glee.

But what were they then, these devilled almonds so like Edith Sitwell’s earliest verses? Older recipes seem to suggest these were almonds lightly fried in butter with cayenne pepper and salt. But an 1887 cook book, High Class Cookery Recipes by Mrs Charles Clarke (1887) lists them under ‘Curries and Indian Dishes’, where curry powder is used as an alternative to cayenne. The Land and Water critic evidently wishes adroitly to convey the exotic and rather bracing quality of the poems.

The book itself is full of parrots, pierrots, fairgrounds, fairy tales, clowns, marionettes, apes, choirboys, spinsters and spinach, and is glorious. Compared to the careful nature studies of the then ascendant Georgians, it is a riot of colour and artifice, and against their gentle lilt it goes full tilt, in poems that read like chants and psalms and fanfaronades. Nothing like it had been seen in English poetry before. Sitwell’s role in modernism is rarely celebrated (and even disputed) yet this volume alone demonstrates how original, cosmopolitan and experimental she was.

When I read through the entirety of The Chatto Book of Modern Poetry edited by C. Day Lewis and John Lehmann (1956), she and Eliot and Auden were about the only ones (aside from war poets) who did not write about the countryside. There’s only so many horses and hedgerows you want. Even the city poems were about London parks and Kew Gardens. So we should not under-estimate the boldness of Sitwell’s palette. Certainly there is a rather hectic pace and a love of the bizarre and the vivid for its own sake, but the impetus of the book is to push poetry closer to other forms of art, particularly music, ballet and abstract painting. This soon led to the brilliant and provocative Façade (1923), set to music by William Walton and performed in a mask through a megaphone.

Despite her origins in landed gentry, Edith Sitwell’s upbringing and youth had not been easy. Her father was an eccentric with fixed ideas and her mother a spendthrift later imprisoned for fraud. The poet had lived if not in penury exactly then certainly in strict circumstances. The author of another innovative book of poetry published 100 years ago had an opposite sort of background. In the preface to Otherworld: Cadences, F.S. Flint tells us: ‘I am not a scholar in any sense; I have dabbled a little in languages and browsed a little on literature; but the chance of life has made me a wage-earner since I could read and write almost.’ He was, of course, a scholar, but a self-taught one, and he worked as a clerk in the civil service, later becoming an expert on economic statistics at the Ministry of Labour. But he was also part of the Imagist circle with Ezra Pound, H.D., T.E. Hulme, Richard Aldington, to whom the book is dedicated, and others. Aged 35, this was his third original volume of poetry (there were also translations), following In the Net of Stars (1909) and Cadences (1915), which introduced the term he preferred for his work.

When I got my copy, discarded from the Robert Scott Library of Wolverhampton Polytechnic, I was at first disappointed by the contents. I had been expecting the brief precise imagery shown in such exquisite pieces as Pound’s ‘In a Station of the Metro’. But these were much longer and plainer: and they were confessional, autobiographical. It took me a while to adjust, but I soon found that there was an integrity and clarity about the work that won me over. In his preface Flint advances three propositions about poetry. It is ‘a quality of all artistic writing, independent of form’; secondly, ‘rhyme and metre are artificial and external additions’ which have become ‘worked out . . .insipid . . .contemptible and encumbering’; and thirdly ‘the artistic form of the future is prose, with cadence—a more strongly accented variety of prose in the oldest English tradition—for lyrical expression.’ It is such cadences that he offers in this volume.

Something of this approach had been seen in the work of Whitman, no doubt. But though Flint’s cadences have their flights, they are not usually rhapsodic. There is no special ‘poetic’ diction. This is the plain, almost homely vocabulary of the working clerk. That does not mean, of course, that the subject matter is necessarily down-to-earth. Certainly we are told of his daily commute and the drudgery of the desk, but in the long opening title poem he speculates about another version of himself on a far-away star: and also tells us of a friend, a carpenter, who made the poet’s own study chair and grows roses, who sees different shapes in the heavens than the usual constellations.

In contrast to Sitwell, Flint’s work is highly interior, mulling sombrely over his thoughts and feelings, and unlike her crowded cast of colourful characters, he usually walks alone or with one companion. Its effect is cumulative rather than immediate. There is some affinity perhaps with the blunt, rough-hewn work of the Northumberland poet Wilfred Wilson Gibson, but that sometimes retained archaic language and folkloric content, whereas Flint is more focused on the contemporary. He has rarely had his due as a poetic innovator behind his more flamboyant fellow-Imagists, but this volume shows the quality of his thought and his work.

A.A. Piggot, whose posthumous Poems was also published in 1920, has more in common with Sitwell than with Flint. He may not seem obviously avant-garde. This is a commemorative volume collecting most—but significantly not all—of the verses he had published, no doubt at his own expense, in three slim booklets from local Cambridge presses, with the aesthetical titles of Chiaroscuro (1911), Mezzotints (1912) and Bas-reliefs (1913). It adds some later work. A preliminary page reads and looks like a memorial tablet: ‘ARTHUR ALFRED PIGGOT,/B.A., LL.B./Born October 18th, 1891/First-Class Honours Classical Tripos,1913’ then other academic achievements, followed by ‘Lieutenant, 13th Service Battalion, Northumberland/Fusiliers/Wounded and Missing, Hill 70, Loos, France, Sunday/Morning, September 26th, 1915’.

Piggot wrote in a neo-Decadent mode, influenced by the Yellow Nineties of Wilde, Beardsley, Dowson and others. He was not alone in this: James Elroy Flecker at first adopted the fin-de-siecle fashion too, and some of its fatefulness and rather swooning imagery can be seem in the work of Rupert Brooke, Wilfred Owen and others of the Great War generation. But Piggot was more fervent as an acolyte of the Nineties: two of the poems left out of the 1920 book are about doomed boys and mandrakes. In his last poems he tries to preserve his aesthetical sensibility in the trenches, and there is a delicate courage in the striving. The final verse, ‘In Billets’, evokes a chateau, ‘dull cardboard white’, trees with branches ‘like peacock’s feathers’, drifting mists, laughter in a lighted hall, but ends with the patient roaring of the far guns.

His work is mannered, certainly (that is rather its point), but it has a delicious flavour quite remote from the flag-waving and bugle-sounding of the patriot (and often fireside) poets who sprouted when war was declared. His verses are a sultry pleasure in themselves but they also illustrate how neo-Decadence may be seen as a perfume in the air that scented the early Modernists, wafting through Eliot and Pound, with Yeats carrying his own patchouli with him from the days of what he called the Tragic Generation.

It is a bravura pose, the Neo-Decadence, that would have amused and delighted the dandy and bon-vivant Brian Howard too. He never published a book of poetry, was a mercurial presence in the life of Evelyn Waugh and others, and a 2005 biography by Marie-Jaqueline Lancaster is entitled Portrait of a Failure. But in 1920 there was work by him, under a pseudonym, in modernist periodicals, and he was later included in Sitwell’s Wheels. It is difficult to tell whether these were genuine radical experiments or high-spirited persiflage—probably a bit of both, but they certainly have élan.

As Jasper Proude he published in The New Age of May 13 1920 a poem called ‘Balloons’: ‘Up, up they go – up,/Luminous sides, rotund, of candied veneer,/Flouting their painted sheens’. This has the aery, floaty, vivid quality of its subject but characteristically ends with a terse and tired ‘Balloons, damned Balloons.’ More adventurous still is ‘The New New’ (July 22 1920), a sort of weary stream-of-consciousness commentary on the very latest fads, nodding to Vorticism, Dadaism, Sitwell’s Wheels, Roger Fry’s Omega workshops, and ending with the Firbankian exclamation, ‘How catching it all is!’

Another ultra-bohemian was Iris Tree, whose Poems was published in 1920, by the Nineties publisher John Lane, with a frontispiece photograph of Jacob Epstein’s cubist head of her, with long closed eyelids and pointed upper lip. She was only 23 but already had a torrent of poems to her name. There is also a decoration on the title page, by her husband Curtis Moffat, depicting six very Beardsleyish tall glowing candles with wax tears dripping down their columns. Fire pervades the titles of the different parts of the volume: ‘Rockets and Ashes’, ‘Smoke’, ‘Flame’, ‘Lamplight and Starlight’. We might be reminded of some of the imagery of the Nineties: the arch-Decadent Richard Le Gallienne’s evocation of London lampposts as ‘the iron lilies of the Strand’ or Arthur Symons’ attentiveness in his verses to the spiralling of cigarette smoke.

Tree’s poems do not at first match the modernity of Epstein’s portrait of her: some are closely rhymed and not especially original in sentiment. But others are in freer verse and make adroit use of syllable echoes and half-rhymes. Tree evokes some similar images to Sitwell— toys, clowns, figures from the Commedia dell’arte—but in her case also registers a weariness that knows the shabbiness behind the scenes of all this play, ‘How starved the juggler, mean and miserly,/And life a laboured trick.’

Other themes are assertively modern. Her poem ‘Zeppelins’ for example, has four parts each set in the hours of the night during the wartime raids on London, and evokes the dramatic effects of the fires, the boom of the guns, and the excited, panicking people, rather than the airships themselves. It eschews any indignation or calls for vengeance, as would be the stock reaction from traditional poets, and frankly admits to the thrill and the glamour that was also experienced. The hubbub and the clamour are exciting. In the first poem ‘Midnight’, she exclaims ‘How swift runs fear: quicksilver that is free!’ It ends with an arrogant proclamation of self-realisation: ‘Yet will I toss the dust of sheets away,/Yet will I be mistress of the sun!’

Aesthetical touches are never far away: the ‘intricate patterns of the scaffolding’ drawn against the sky at 3 a.m. is ‘more delicate than lace’ while the ‘shimmering lights’ are disappearing to morning ‘As a blue peacock sheaves his starry tail’. The fervour and effusion of her verse is far away from the calm, measured tone of the Georgians, and suggests another way out from the sturdy solemn work of the drawing-room Edwardians.

The study of the poetry of 1920 understandably gives priority to the important books that were published in that year by those now chiefly thought of as war poets: Wilfred Owen’s Poems, Siegfried Sasson’s Picture Show, Edward Thomas Collected Poems, Edmund Blunden’s The Waggoner. The history of modernism celebrates the publication of Pound’s Hugh Selwyn Mauberley and Eliot’s Poems, perhaps stretching out a little to Aldous Huxley’s Leda. But these other less celebrated volumes are worth attention both in their own right, as original and charismatic works, and as testaments to future possibilities in poetry, possibilities which have perhaps still not yet been fully explored.

Comments

One response to “Devilled Almonds and Doomed Boys: some avant-garde poetry of 1920”

[…] Mark writes for Wild Court on some avant-garde poetry of the 1920s here and some student poems of 1965 […]