Dave Coates

The Helmet

When shiny Hector reached out for his son, the wean Squirmed and buried his head between his nurse’s breasts And howled, terrorised by his father, by flashing bronze And the nightmarish nodding of the horse-hair crest. His daddy laughed, his mammy laughed, and his daddy Took off the helmet and laid it on the ground to gleam, Then kissed the babbie and dandled him in his arms and Prayed that his son might grow up bloodier than him.

The Parting

He: ‘Leave it to the big boys, Andromache.’ ‘Hector, my darling husband, och, och,’ she.

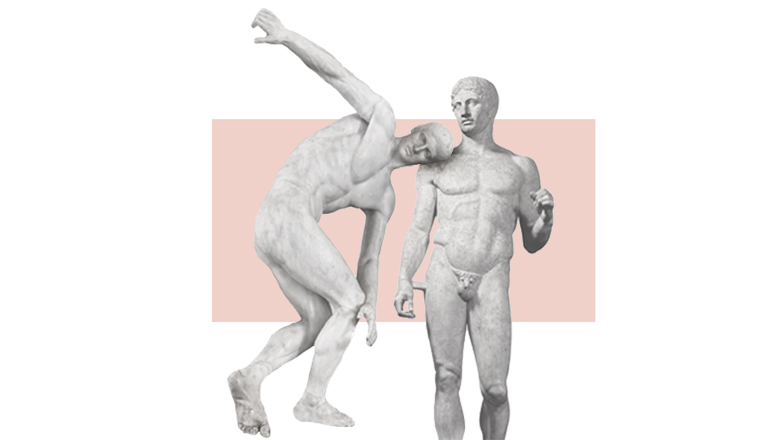

Aside from a few relatively brief and often oblique references, the non-normative gender politics and sexualities in Michael Longley’s work have yet to be critically examined. Terence Brown noted that Longley’s oeuvre has, from the beginning, articulated a kind of erotic exchange more mutually respectful and less domineering than was norm in 1960s Irish poetry. Brown frames this strand of his work in spiritual terms, in which ‘the strangeness of erotic experience’ becomes ‘humankind’s most profound, even sacral, experience of interconnectedness with a material universe’. Challenging heteronormative attitudes to sex and gender is as vital (and frequently recurring) in Longley’s work as his more often celebrated war poetry. This essay will examine a few poems from the 1990s in which a nurturing, emotionally accessible masculinity is presented in opposition – or as an alternative – to the domineering, destructive kinds critiqued and parodied in the poems above.

Neil Corcoran’s essay, “The poetry of botany in Michael Longley”, begins with an examination of how The Ghost Orchid (at the time Longley’s most recent collection) ‘reduc[es] male presumption and arrogance and remind[s] us of the instabilities of gender differentiation’. From the short poem Mr 10 ½ after Robert Mapplethorpe:

I find myself considering his first months in the womb As a wee girl, and I substitute for his two plums Plum-blossom, for his cucumber a yellowy flower.

Corcoran discusses how both source photograph and poem have comic or ironic undercurrents, and the poem playfully criticises aggressive formulations of masculinity by reimagining the male body. Here, Longley points to a pertinent fact – the lack of fixed biological gender in the womb, never mind learned social roles later in life – to unsettle the perceived gender differences that underpin formulations of male superiority. Gender fluidity repeatedly stands in Longley’s work against systems of inherited male violence.

In her book-length study, Reading Michael Longley, Fran Brearton does important work in establishing how his ‘betwixt and between sensibility’ maps onto his rendering of interactions between men, particularly in his versions from Homer, such as ‘Laertes’ and ‘Ceasefire’, discussed below. Her reading tends to focus on Longley’s classicism, formal accomplishment and political import, of which there is now a substantial body of scholarship; the facts of the poems’ homoeroticism or concern with physical expressions of platonic love are largely unexplored. That Longley’s work repeatedly makes space for nuanced expressions of gender and sexuality makes him rare in Northern Irish poetry, and almost unique among poets of his generation; acknowledging this aspect of a near-canonical body of work seems overdue.

In ‘Laertes’, Longley plays out a difficult emotional exchange between men through Odysseus’ delayed reunion with his elderly father. Odysseus’ frustrated desire to make physical contact delays the reunion further, as he retreats into memories of childhood:

[…] all he wanted then and there Was to kiss him and hug him and blurt out the whole story, But the whole story is one catalogue and then another, So he waited for images from that formal garden, Evidence of a childhood spent traipsing after his father

Odysseus’ association of familial affirmation and literary instinct (the ‘story’, the ‘catalogue’, the double meaning of ‘that formal garden’) seems significant. Poetic fatherhood is a recurring theme in Northern Irish poetry, and the poem is perhaps in dialogue with Heaney’s early poems. In ‘Digging’, from Death of a Naturalist (1966), Heaney struggles to assert his aptitude for writing against the more traditionally masculine qualities of his father (‘By God, the old man could handle a spade’) and his father’s father (‘My grandfather cut more turf in a day / Than any other man on Toner’s bog’). ‘Laertes’ also echoes ‘The Follower’, from the same collection, which concludes:

I was a nuisance, tripping, falling, Yapping always. But today It is my father who keeps stumbling Behind me, and will not go away.

Where Heaney’s relationship is characterised as adversarial and burdensome, Odysseus is emboldened by his memory of a nurturing father, Laertes providing his son with words and understanding of the natural world, specifically in the domestic space of the family orchards:

And asking for everything he saw, the thirteen pear-trees, Ten apple-trees, forty fig-trees, the fifty rows of vines Ripening at different times for a continuous supply

Though Laertes’ gift to his son of both language and food is described as sustainable and life-giving, their reunion as adults is silent. Where filial bonding in ‘The Follower’ is uncertain and anxious concerning physical closeness, the bodies of Laertes and Odysseus create space for expression when words fail:

Until Laertes recognised his son and, weak at the knees, Dizzy, flung his arms around the neck of great Odyssesus Who drew the old man fainting to his breast and held him there And cradled like driftwood the bones of his dwindling father.

The image of Odysseus holding his father ‘fainting to his breast’ marks his body as a site of nurturing or protective love, belying his wartime reputation as ‘great Odysseus’. Brearton reads this scene as working ‘a reverse angle’, in which Odysseus becomes father-like and Laertes like a child ‘cradled’ in his arms. The exact wording is significant, however; given how often breasts feature in Longley’s work, it seems reasonable to connect their presence here to other important instances. In ‘Peace: after Tibullus’ (1979):

As for me, I want a woman To come and fondle my ears of wheat and let apples Overflow between her breasts. I shall call her Peace.

‘The Linen Industry’ (also 1979):

Let flax be our matchmaker, our undertaker, The provider of sheets for whatever the bed – And be shy of your breasts in the presence of death

and, not far from ‘Laertes’ in the same collection, ‘Icon’ and ‘X-Ray’,

I could not believe that when you came to die Your breasts would die too and go underground.

From Icon

because it is April nineteen thirty-nine I should look up to the breasts that will weep for me And prescribe in the dark a salad of landcress, Fennel like hair, the sky-blue of borage flowers.

From X-Ray

This is by no means an exhaustive list, and in each example breasts clearly carry important symbolic meaning as images of natural plenty or maternal protection, often in direct opposition to war and death. It is worth noting that this is a relatively reductive symbolic system, far more conventional than his renderings of masculinity. This seems a crucial point, however: in Longley’s poems, men’s breasts also function as a site of parental care-giving. A later Homeric poem, ‘In the Iliad’ (2000) describes how:

When I was left alone with our first-born She turned in the small hours her hungry face To my diddy and tried to suck that button.

In this context, when Odysseus acts as care-giver in the un-epic space of Laertes’ garden, he seems to embody Longley’s ideal masculinity, encompassing strength and compassion, eroding the harmful binaries imposed by traditional gender roles.

In Longley’s 1995 collection, The Ghost Orchid, versions of Ovid’s Metamorphoses occasion his most explicit references to subverted or destabilised gender signifiers; again, the guise of classical literature permits a kind of serious playfulness that seems to have helped these poems pass Longley’s critics almost unnoticed. Amongst several more direct versions of Ovid is ‘A Flowering’, a poem that seems far more personal and candid:

Now that my body grows woman-like I look at men As two or three women have looked at me, then hide Among Ovid’s lovely casualties – all that blood Colouring the grass and changing into flowers, purple, Lily-shaped, wild hyacinth upon whose petals We doodled our lugubrious initials, they and I, Blood dosed with honey, tumescent, effervescent – Clean bubbles in yellow mud – creating in an hour My own son’s beauty, the truthfulness of my nipples, Petals that will not last long, that hang on and no more, Youth and its flower named after the wind, anemone.

Here, Longley makes more explicit the connections between physical and metaphorical gender signifiers, drawing again on the homology of male and female bodies; the poet’s non-functioning male nipples present a physical marker of the poem’s ‘truthfulness’, that even biologically there is little enough cause to assert gender difference with any confidence. As in ‘Laertes’, ‘A Flowering’ is composed of a single, manifold sentence, from which it is difficult to satisfactorily pin down a prosaic meaning. The connections between the flowers on which the poet and ‘Ovid’s casualities’ write and the beautiful bodies this writing seems to create do not seem to abide rational causality; the entire poem seems intent on both expressing itself and remaining hidden.

It seems significant that this impulse towards secrecy is explicitly connected to homosexual male desire and a rejection of physiological gender binaries. The related episode in Metamorphoses is Aphrodite’s lament for the death of Adonis, wounded in the groin by a wild boar. Where the poetic I resides in relation to this story is ambiguous; with the woestricken Aphrodite (mother of Hermaphrodite, a fact the classicist Longley may have had in mind), or the beautiful, dying young man who might be ‘[his] own son’, or his younger, once-heteronormatively desirable self? The poem’s semantic fluidity seems a deliberate feature, the suggestive botanical imagery a fig leaf for the direct expression of transgressive desire in the poem’s opening lines; that Longley sees the need for disguise suggests unease about the poem’s reception, both critically and in a broader cultural setting.

Also in The Ghost Orchid is ‘Ceasefire’, first published in The Irish Times a few days after the first IRA ceasefire in August 1994. The poem selects four moments from the meeting of Achilles and Priam at the close of The Iliad, after the death of Hector, Priam’s eldest son and heir to the Trojan throne.

I Put in mind of his own father and moved to tears Achilles took him by the hand and pushed the old king Gently away, but Priam curled up at his feet and Wept with him until their sadness filled the building. II Taking Hector's corpse into his own hands Achilles Made sure it was washed and, for the old king's sake, Laid out in uniform, ready for Priam to carry Wrapped like a present home to Troy at daybreak. III When they had eaten together, it pleased them both To stare at each other's beauty as lovers might, Achilles built like a god, Priam good-looking still And full of conversation, who earlier had sighed: IV 'I get down on my knees and do what must be done And kiss Achilles' hand, the killer of my son.'

The poem’s position in Gorse Fires – between ‘The Campfires’, in which fifty thousand troops wait for an attack at sunrise, and ‘The Helmet’, in which Hector wishes bloodthirstiness on his infant son – suggests an awareness of the ceasefire’s contingency. The war will continue, Achilles will be killed by Priam’s son Paris; and both Priam and Astyanax, Hector’s son, will be killed by Pyrrhus, son of Achilles.

Although ‘for the old king’s sake’ hides Achilles’ fear of retribution in the original, the poem’s formal breaks hold the action suspended in time between one phase of the Trojan war and another; even section IV, occurring in the original before the action in section I, envelops the narrative and embodies a process of continuous forgiveness, empathy and love. The catalogue of revenge killings are replaced by Achilles’ recognition of Priam as a surrogate father, and, after the gift of food and funeral rites (itself a manner of hands-on care-giving), by a moment of calm, physical intimacy. Once again, Longley figures an embodied kind of homosocial bonding (bearing in mind the three appearances of ‘hands’ in such a short poem) as central to a healing process that counters violence and death.

* * *

These poems figure systems of male social exchange – erotic or otherwise – as a continuously shifting site of love and care-giving, and formulate a masculinity that can accommodate such systems. While the classical backdrops of these poems might at first appear distant from contemporary concerns, their depictions of non-normative and fluid gender roles depicted are a vital aspect of Longley’s resistance to war and violence. His poems emphasise the role traditional masculinity has to play in creating cultures of violence, and render recurring acts of personal, emotional generosity as acts of political resistance.