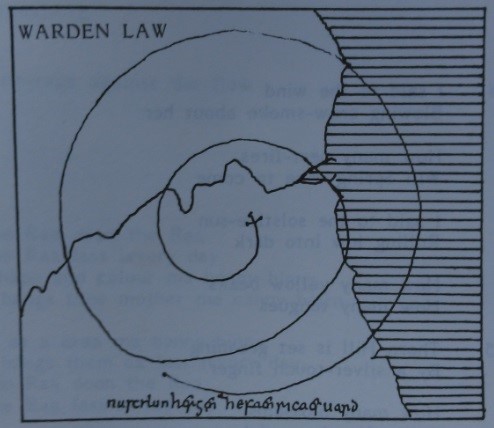

‘Cuthbert’s brief dream / And high resting place / Here before Durham’ (s.16): Warden Law by William Martin, part of ‘Wiramutha Helix’

Jake Morris-Campbell

Next year marks the tenth anniversary of the death of the late poet, William Martin (1925-2010). A self-professed son of the Haliwerfolc (followers of Saint Cuthbert, a seventh-century monk whose miraculous healing abilities made him a lodestar of early Christianity in North-Humberland and original proprietor of Durham Cathedral, constructed to house his remains after they’d been carried by his devotees from the Viking-sacked coast at Lindisfarne), Martin’s poetry honoured the religious iconographies of the North-East by fusing them with the Eastern spiritual traditions he was exposed to while working as a radio technician for the Royal Air Force in Karachi during the Second World War. Born in New Silksworth, County Durham, in 1925, he traced the fortitudes and fractures in the autarkic mining communities of North-East England as they boomed and collapsed during his lifetime. Taking inspiration from a plethora of Romantic and biblical sources, and drawing on the Gravesian notion of the Goddess as an ancient figure of care and nourishment, Martin’s poems are ripe to speak to the precarity and populism gripping the world today, guiding us from the regressive lure of isolationism towards – kitsch as it sounds – something truly wholesome.

The neologism Martin coined to explore his vision, tying together as it did two apparently-opposed strands – ancient Orientalism meeting the dying Empire – was ‘Marradharma’. Combining his socialism, inculcated by virtue of his birth at or near the peak of carbon extraction from the Durham coalfield, with the all-encompassing notion of the ‘dharma’ (in Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and other religious traditions, ‘dharma’ roughly means ‘the way’), Martin’s blend term became a tantric force used to underscore a poetic practice achieving the seemingly impossible task of both remaining firmly rooted in its own origin myths yet being supple enough to send out satellites, transmitting mantras, legends and political solidarities from elsewhere, re-coding, enmeshing and incorporating them into a discrete collage.

Indebted to high modernist figureheads like David Jones and Basil Bunting, his influences weren’t chiefly literary. His palette and easel drew upon painters such as Samuel Palmer, while the illustrative-poetic mode used by William Blake (to whom Anne Stevenson has compared him) are a clear influence. More broadly, the oral and tactile arts of Northumbria’s Golden Age, spanning centuries of folk music and ballad and the production of illustrated manuscripts and codices, intersperse his poetry to the extent that one is never fully certain if the poem begins (or ends) at its textual limits, or whether we’re supposed to ‘read’ the work within a much broader context, obliging us to reconsider what we might understand by the communal arts. His is a poetics in which the nexus of politics and society, the individual and the state, are refracted through artworks-as-receptacles for a renewed sense of common culture. Roger Garfitt said of him: ‘William Martin is a remembrancer, patiently polishing the common coins of street games, folk songs and customs, and putting them back into circulation […] eschewing private poetry to restore the collective symbols, releaf the ikons with gold’. I often think of Martin as my wife and I walk the beaches of Marsden and Whitburn: the pebbles from those crumbling cliffs litter my bookshelves, reminding me that my work as a writer owes a large debt to the material realities of where I am from.

Being born in and residing ten miles north of where Martin spent most of his life, in a patch of land between the mighty industrial rivers that make up the metropolitan county of Tyne and Wear, I am intimately connected to this place. Like Martin, I spend a lot of time thinking about how my writing and poetry might cherish and praise these landscape histories while being self-effacing enough to recognise that tribalism and scapegoating have been given frightening new legitimacy in an area historically prone to bloodshed.

In 2016, having spent a year reading Martin’s oeuvre (collected in two pamphlets and four full-length collections, spanning 1970-2000) and emboldened by endorsement from his son, Graham, I decided to re-create a pilgrimage that Martin made each summer solstice from his home in Sunderland to Durham Cathedral. Along the way, he would trace the route made centuries earlier by the Haliwerfolc, palimpsesting onto the byways’ recently-extinguished glyphs memories of coal-waggons which cut tracks through his boyhood dreams as black diamonds were loaded at Rhyhope and Silksworth, shunted down the gravity line at Warden Law and hauled on to ships at Seaham Docks to fuel the furnaces of extractive capitalism.

Approximately fifteen miles long, roughly paralleling the modern-day A690 and bisecting north-east County Durham at a diagonal, the walk is not so much a Selfian dérive as a beating of the bounds. According to E.P. Thompson in Customs in Common (Penguin, 1993), ‘[at] the interface between law and agrarian practice we find custom’, thus Martin’s pilgrimage fostered the ‘continual renewal of oral traditions, as in the annual or regular perambulation of the bounds of the parish’ inviting members of the community to come together and traverse a landscape imbued in signifiers held dear by its bardic instigator.

For William Martin, the walk was always about returning. Each year he would set out with a troupe of friends and family, fellow poets and artists in tow, walking a route he had devised along grown-over railway lines. From the stone bridge at Framwellgate, the river Wear snakes around Durham, its great, Gothic cathedral looming above the compact city. The cathedral, then, is the hub, and the spokes are the former coal and steel towns making up the outlying communities: Horden, Peterlee, Consett. Around the same time each year, many thousands of people make their own way to this gathering spot, where colliery banners are blessed before political speeches and rallying calls are proclaimed on the nearby racecourse.

For Martin, this was a focal point of the year and emblematic of socialism in action; his Marradharma functioning in real-time. Witness his description of the ‘Big Meeting’, as it is colloquially known:

Black marra banners Thump! Sounding brass slowly Thump! again Climb the hill Thump! the big drum goes

(‘How Many Miles to Babylon/Anna Navis’, Marra Familia, Bloodaxe, 1993)

‘Marra’ is a dialect term associated with Durham, Northumberland and parts of Cumbria: with shipbuilding, coal and lead-mining, heavy industry and farming. Marrows grew in the soil the way comrades once descended the pit-shaft, toiling beneath. While men (and, often, boys) dug the coal, the whole community burned it. Hence, subterranean labour was matched by camaraderie on the surface, with women, children and elders all pitching in: supporting others when times were tough, such as when a nearby lodge was on strike or became unproductive. Marradharma, which came for Martin to be a way of unshackling from patriarchal tracts associated with a traditional kingdom, meant something like the way of the marras—perhaps best understood as not being gender-bound. Doubtless, the world Martin grew up in was male-dominated, and one could feasibly argue a disconnect between his harmonious imagery and the lived experience of miners’ wives, but I think it’s important to note that in turning to the notion of the Goddess (personified by the ‘vulva denes’ and ‘mothergates’ throughout his poetry), the aim was to valorise a truly socially-democratic society, one whose roots went back to the matriarchal notion of the earth as caregiver and provider. Decades of hard-won union endeavour and collective effort made this possible. We get a sense of the joyous side of this solidarity in another of Martin’s many poems featuring the Gala:

They were preached at And played at Tom the drummer Playing in his last Meeting with Polly And Polly the blood And fire army keeping Him on the straight And narrow but O For the beer tent The pint froth And pit talk

(‘Malkuth’, Hinny Beata, Taxus, 1987)

In documenting the Durham miners and their annual convergence, Martin’s work spotlights the individual amid the crowd, revealing the humility in a serious spiritual and political spectacle. As Lee Hall has written:

In remembering, celebrating, lamenting our mining past, we’re not paying homage to the dirt, the exploitation or the circumscribed lives of our forefathers and mothers. We are acknowledging their hope, their aspiration for a better world […] their willingness to deprive themselves individually to fight for the common good.

(‘A History Still Being Written’, The Miners’ Hymns, BRASS Durham International Festival, 2010)

Those who feel that a communitarian society has been usurped by full-blown, Thatcherite individualism will doubtless decry Martin’s work as redundant. Read thirty-five years later, however, amid the country’s biggest peacetime upheaval, his poems seem to me to offer vital guidance on how we might negotiate a path through the mires of nationalist populism and the mirage of what the French philosopher Bruno Latour has called ‘Out-of-This-World’ Trumpian politics: ‘the headlong rush toward maximum profit while abandoning the rest of the world to its fate’ (Bruno Latour, Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime, Polity Press, 2018). As I walked the pilgrimage for the third time last summer, I had legitimate reason to begin doubting its significance. Beyond the school of thought which would castigate Martin’s work as being socially and politically anachronistic, the lengthening shadow cast by Brexit made me worry at how I use my privileged position as a poet and critic (educated latterly via taxpayers’ cash to doctoral level) to explain the enduring, universal significance of his work. Skirting some of the most deprived communities in England, many of which voted heavily for Brexit, I had a crippling sense that our walk – lovely as it was, flanking fields studded with poppies, traffic often far in the distance, thoughts of the brittle biosphere temporarily supressed – exists now in an academic vacuum: that its inherent meaning is limited to the diminishing number of people who knew Martin and that the thought of ‘beating the bounds’ is simply inimical to most people, who wish, entirely fairly, to use their Saturdays to shop, relax, be hungover, cheer on their team.

Grounded in what Anne Stevenson has called ‘a gallimaufry of Christian, Gnostic and pagan images’ (About poems and how poems are not about, Bloodaxe, 2017), Martin’s work began tapping into what Latour now registers as a vital necessity to return to the ‘terrestrial’; that is:

[…] conflict between modern humans who believe they are alone in the Holocene, in flight toward the Global or in exodus toward the Local, and the terrestrials who know they are in the Anthropocene and who seek to cohabit with other terrestrials under the authority of a power that as yet lacks any political institution.

If Martin’s poetry partially functioned as proud bulwark to the fiscal and technocratic forces that historically denied the working-classes of County Durham autonomy, reaching cruel apogee during the 1984-85 miners’ strike, how do we read its importance now? While its placed, Goodhartian ‘somewhere’ tendencies (David Goodhart, The Road to Somewhere, Penguin, 2017) appear at first to be at odds with Jahan Ramazani’s idea of ‘poetic transnationalism’ (Jahan Ramazani, A Transnational Poetics, University of Chicago Press, 2009) the work, for me, speaks to the need for what I’ve begun calling polyparochialism. Noting that ‘there is something near worship in each of Martin’s illustrated volumes’, Stevenson adds the caveat that ‘it is not easy to follow the lines of what is clearly a structured plan’, but concedes that the effort is more than worth it in order to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with ‘an all out vision of a golden kingdom, the glorious Malkuth or Marradharma his imagination never ceased to celebrate in the culture of labour, poverty and struggle that fed the precious stream of human life he commemorated.’ Stevenson’s reading of the sacramental qualities of Martin’s work seem to me appropriate and relate to something I’ve been thinking about as I read his poems and trace his pilgrimage: his ambassadorial spirit was proudly rooted, but he knew it ultimately to be exogenous, reflecting the extensive immigrant culture the North-East was founded on.

It’s a big word, ‘ambassador’, but the more I think about it, the more it fits Martin’s poetics. A better synonym might be ‘custodian’. Where ‘ambassador’ runs the risk of tourist board views of space and place (officiated, conservative, restricted), ‘custodian’ necessarily garners subjectivities and biases. A certain comeback to this view – let’s call it the (simplified) Goodhartian ‘anywhere’ perspective, that of the liberally-minded cosmopolitan who claims no allegiance other than global citizenship – would say that Martin’s poetry – derivative-because-parochial – is doing a disservice to the notion of custodianship; that poets cannot, should not – must not – work to be mouthpieces for anything other than their own imaginative interpretations of a wider world. Patrick Kavanagh, Irish parishioner par excellence, wrote:

[…] Parochialism and provincialism are direct opposites. The provincial has no mind of his own; he does not trust what his eyes see until he has heard what the metropolis – towards which his eyes are turned – has to say on the subject. This runs through all activities. The parochial mentality on the other hand is never in any doubt about the social and artistic validity of his parish. All great civilizations are based on parochialism – Greek, Israelite, English […] To be parochial a man needs the right kind of sensitive courage and the right kind of sensitive humility.

(Patrick Kavanagh in A Poet’s Country, Lilliput Press, 2003)

For John Tomaney, ‘parochialism is not an end state but one of becoming; we are always becoming native.’ (John Tomaney in Reanimating Regions: Culture, Politics and Performance, Routledge, 2017). Noting how the Walibri people of Central Australia see ‘place as a knot of entangled lifelines’ (Tim Ingold, Lines, Routledge, 2016), Tim Ingold’s conception, much like Tomaney’s, is acted out by Martin’s chorographic poem-sequences. As he beat the bounds of County Durham, sharing its idiosyncratic landscape features and half-hidden industrial vestiges with new friends (like Roger Garfitt, who in the early 1990s was acclimatising to the realities of the region, having arrived to facilitate writing groups in nearby Blyth) Martin was able to conduct his inhabitant knowledge, transmogrifying it through his poetry. For Ingold, this procedure sees:

Every place, [as] a knot in the meshwork, and the threads from which it is traced are lines of wayfaring. It is for this reason that I have consistently referred to wayfarers as inhabitants rather than locals, and to what they know as inhabitant rather than local knowledge. For it would be quite wrong to suppose that such people are confined within a particular place, or that their experience is circumscribed by the restricted horizons of a life lived only there.

The close of this essay will outline more thoughts on walking the pilgrimage, cross-referring to the sections in ‘Malkuth’ that match points on route, before ending on a general invitation to join with us in the future as we traverse the terrain once more.

Crowned heads rise early In brass morning sun Sleepers resurrected Out of black earth Steel rollers and bobbins Smashed under hammer Scrap-value line Built over and ploughed Only feet bring remembrance

(‘Anna Navis’, Marra Familia, Bloodaxe, 1993)

Easthope

We are cast Onto the ground It was yesterday In the morning (s.7)

It is 8.20am. We are shivering in the garden of Easthope, the one-time home of Bill Martin. Graham is digging a rectangular hole out of the lawn, ready to pour the first portion of the remaining ashes of his father into the earth. We sing Bill’s original folk song, ‘Up the Leafy Lonnen’, contemplating the journey ahead as well as journeys past.

They all sing to bring them together Live tableau spectrum (s.10)

We don rucksacks and walking boots and head for the Maiden Paps. A joke is made about sons bearing the weight of fathers. Passing cars on the Leechmere Road give us more than a fleeting glance.

Warden Law

The path is Indeterminate At first 1822 line grown over Track to the city cut across Bridges down and Crossings uprooted Ghostly primal waggons Through clouds of Brick and tarmac (s.13)

We arrive at Warden Law, where the only sounds are the wind whipping off the North Sea and the buzz of four-stroke engines from go-karts whizzing around the track below us. Graham’s camping shovel, which he has brought in order to dig into embankments along the route to scatter then cover the remainder of his father’s ashes, has seized shut. Our failed attempts to re-open it can only be described as slapstick. He sprinkles from the urn anyway, and I read: ‘If I cry cockerooso | Generations hop across’ (s.11). Looking north over the vista spread out before us – Wearside in the foreground, Tyneside in the middle, the Cheviot Hills far off in the distance – I show people another poem, ‘Wiramutha Helix’, noting the Warden Law section specifically. Stood here in years gone by, Bill joined the dots, marshalling the vista, seeing its scattered contours and histories not as disparate elements, but as a wholesome, living cosmos. Fixed on a certain point, his wayfaring was always recursive, communicating information from afar, sifting and co-mingling it with knowledge from nearby.

Thorn Hill has a crack Full of green fossil stars How many blinded Will see them rise

(‘Wiramutha Helix’, Hinny Beata, Taxus, 1987)

Pilgrims, 1990s. William Martin is fourth from the right. Photo courtesy of Peter Armstrong. (Click to enlarge)

Copt Hill/Seven Sisters

Show us the way To Durham Lasses with your Dun-cow and milk (s.17)

Approaching the seven sisters round barrow – thought to be a Neolithic burial mound and once enthused over by Tony Robinson on Time Team – debates abound as to the number of trees: we count six, but one legend has it there were seven, with yet another claiming three. Unlike the teenagers crunching Pringles and supping cans of pop in the long grass, we appear to be on slippery territory. Graham scatters more of Bill as I read on, ‘Walking away with / The seashore behind’. (s.20)

Three/Six/Seven Sisters round barrow, Hetton-le-Hole, Sunderland. (Click to enlarge)

Pittington/Gilesgate

Out of dust And Genesis sand She breathed him (s.23)

Is there anything more dispiriting to the pilgrim than a boarded-up watering hole? We mourn the sad passing of the Blacksmith’s Arms, Low Pittington, resolving to plough on to greater refreshments in the city. Clearly the derelict hostelry has caused much distress as we forget to deposit some of Bill at this point – in a field of wildflowers and horses that he used to admire – and instead make the spreading retrospectively, on Bent House Lane, in sight of the Rose Window, one of Bill’s favoured aspects of the cathedral.

We knock at the emptiness Bronze ring hand-lavished (s.28)

Dunholm

Daydreams by Elvet station Mothergate ending (s.45)

Old Durham Gardens resembles a vineyard in Southern France. It is hot and we’ve done fourteen miles on the hoof. We cross the footbridge onto Durham University’s sports complex, where keen Sunday joggers make circuits of the pitch and rowing teams practice for the regatta. We continue on to the Racecourse, where in a fortnight’s time the Marras will assemble once again. Graham pours the remains of his father into the river, making sure to pocket the final grains for the tomb of Saint Cuthbert. It is a symbolic act: giving Bill back to the river he loved so dearly, so that he might be carried downstream, past the city he was from and out into the open waters beyond. Adam Phillips, who has recently worked with students at the University of Sunderland to create a short film-poem of Bill’s work (https://vimeo.com/218791895), reads ‘Precious stone’ – ‘Stones continually / Come from cliffs / And go to sand’ – as we throw the pebbles collected from beaches at Marsden, Roker and Seaburn into the water (William Martin, Easthope, Ceolfrith Press, 1970). We rejoin the throng of people in the city and make our way up the cobbled bank to the Cathedral.

Durham Cathedral

I give you the end As the song weakens (s.46)

It is quiet as we make our way past the nave to Cuthbert’s Shrine. Graham, clearly exhausted from the physicality of the walk, sinks to his knees on a prayer cushion, his hat and bag left to one side, his face pink and creased. He crosses the shrine with the staff he’s been carrying since the morning, before reaching into his pocket and scattering the final particles of his father over and into the floor stones. Using his palm, he rubs the dust into the flags then lights a candle. We all sit in silence for some time as tourists fleetingly pass, uncertain as to the sincerity of the moment.

‘Kingdom lodge banner unfurled’ (‘Malkuth’, s.i)

I wonder how I’ll write all of this down. I have felt a level of connection to Bill’s poetry during these past years which is deep and meaningful, but no matter how much it has touched me, my bond is nothing compared to Graham’s, whose mourning will go on. We exit the Galilee Chapel passing Bede’s shrine where I deposit, talisman-like, my last beach pebble: a curved piece of sea-coal which I found on one of mine and Kate’s recent evening walks on Whitburn beach. It is a practice which the Cathedral forbids but one which Bill saw as being of huge substance: rather than trying to ‘buy their way in’ to Heaven with decorous gifts of jewellery and coins, the common people of Durham – Cuthbert’s true disciples and descendants of the original Haliwerfolc – would instead leave offerings of pebbles; small tokens connecting the gift-giver’s personal pilgrimage back to Cuthbert’s roots on the Northumberland coast and Lindisfarne, forming an emblematic link between the coastal and upland landscapes of this part of the world.

I think about the pilgrimage aspect of the walk, uncertain as to whether it should really be called a pilgrimage. Frédéric Gros reminds us that ‘Thus in Jerusalem as in Rome, the authentic pilgrimage only starts when you arrive’ (Frédéric Gros in A Philosophy of Walking, Verso, 2015). Re-reading Bill’s poem en route, I am minded that his walk – a repeated affair, often reversed at the midwinter solstice, taking him from Durham Cathedral back to his home in Sunderland – was accretive: memories of past walks melding with the present; memorials for long-dead Saints coming to be overshadowed by memorials for too-soon-departed friends (Gordon Brown, a fellow instigator of the walks, committed suicide in 2001). Thus, as Gros says: ‘The radiance of the place itself shrivels the singularity of the stages leading up to it.’

As it was for Bill, arriving in Durham is the climax of eight hours walking, but it is not the end-point. Historically, he concluded each of his summer pilgrimages by bidding the party farewell with the maxim, ‘Next Year in Jerusalem’. While overtly religious in tone, the phrase can be read with a secular eye: ‘Here and here / Is Jerusalem’ in ‘Durham Beatitude’, for example, shows that the quest for spiritual epiphany is itself a helix. Beginning at home, our first ‘here’, it necessarily cascades as an outwardly-spiralling pattern, journeying to other ‘heres’ before turning inward, sojourning once more before recurring again—buoyed on both trajectories by carrying more knowledge than it could on previous trips. Hence, my coining of polyparochialism shows the two-way traffic of ‘the local being enhanced and intensified by listening to the views of the transient’ (John Kinsella, Polysituatedness: A Poetics of Displacement, Manchester University Press, 2017). Gathering for a final group photo on the lawn outside, the journey complete until next year, in Jerusalem, I realise that, like my own poetry and its attempted fidelity to an ever-changing place, this expedition is one without end.

Worm river-bend Cradles them

Worm river-haugh rocks Them laughing to sleep

Worm river-water dreams For them over again

Worm river-mist Covers their silk (s.47)

Pilgrims, 2017 (Click to enlarge)

The Marratide pilgrimages, in honour of William Martin, were revived in 2016. The 2019 walk will take place on Saturday 22nd June. All are welcome.