This essay is the latest in a series for Wild Court by Mark Valentine on obscure publications and poets lost to posterity, and rare books. The series can be found here.

Mark Valentine

In the vast emporium of the Richard Booth bookshop in Hay-on-Wye there used to be four of five high broad shelves filled to overflowing with poetry books. And because these are usually ‘slim volumes’, that meant there were very many of them. I was always on the look-out for forgotten poets of the decadent and fantastical, and so I used to work carefully through these, casting about for any promising titles.

The shop was open until eight o’clock then, an unusual treat in a world where almost everything else shut promptly at five. It seemed a furtive joy to be still among books at so late an hour. The dusk stole through the windows, the passages were dimmed in shadow, and the weak yellow light barely illumined the books. There were few other browsers. I felt like a lonely scholar in some obscure learned library pursuing arcane research, and in a way I suppose I was.

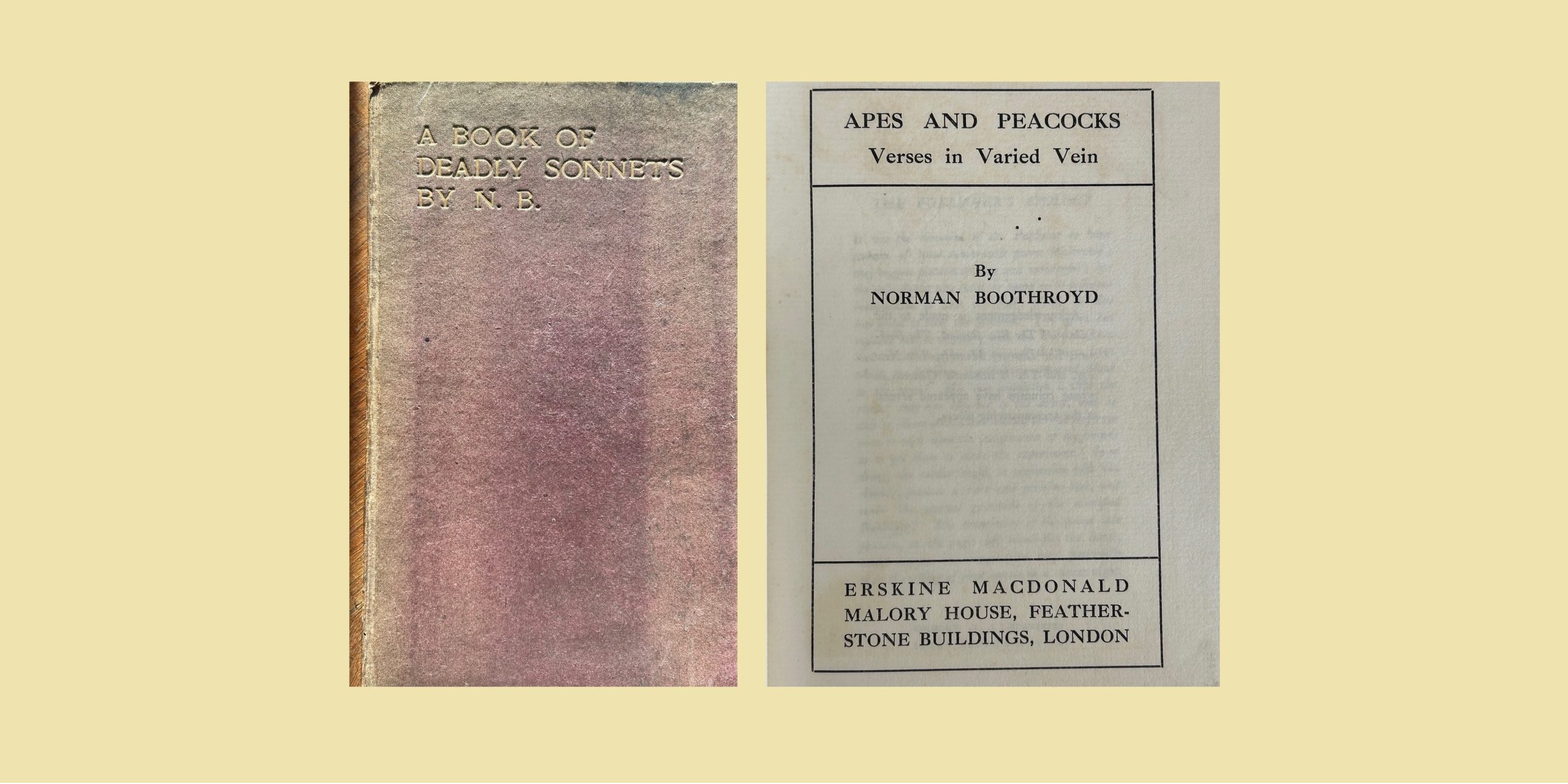

It was on one such occasion that I came across a thin book that was just the sort of thing that I was looking for: A Book of Deadly Sonnets. It was in pale boards of faded plum, with gilt titles. The author was given as just ‘N.B.’. There was no imprint. The black text titles had a vaguely cubist look. I knew I must have it, but looked through anyway to appreciate better just what it was I had found. I caught glimpses of odd words, singular images. So far as I could judge the poems seemed to be in the English ‘nonsense’ tradition of Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll, yet still distinctively different.

The book was probably privately printed for the author and seems to have received little attention. But we know who ‘N.B.’ was because the poems were included in a later volume, Apes and Peacocks: Verses in Varied Vein (Erskine Macdonald, 1913) by Norman Boothroyd.

This did receive some notices. ‘Original, curious, odd and promising,’ said the Yorkshire Post; ‘genuinely bizarre’ thought The Poetry Review. It also received the guarded admiration of First World War poet Edward Thomas, in a review of several books headed ‘New Poetry’, in The Bookman, January 1914:

Mr. Boothroyd’s poems are often professedly descriptions of dreams, and even where they are not, they suit dream logic better than any other. If Lord Dunsany had written verse he would have done something like Mr. Boothroyd. The stately, the mysterious-meaningless, the playful and the nonsensical, are all within his scope. All are good, where excellence would seem impossible… All are like an experimenting verse-writer’s ‘mere idle fantasies of sleep’.

The volume has an epigraph from Fiona Macleod, the alter ego of William Sharp, who was the epitome of the Celtic Twilight in the 1890s: ‘There are dreams beyond the thrust of the spear, and there are dreams and dreams; of what has been or what is to be, as well as the more idle fantasies of sleep.’ As well as the long shadow of Poe and the dim reverberation of Swinburne and the lingering incense of Lord Dunsany’s fantastical tales of gods and heroes, chimera and fabulous beasts, another possible influence might have been James Elroy Flecker’s exotic poems of the Near and Far East, such as ‘The Golden Journey to Samarkand’, which were in current favour. There is also an Arthurian poem, ‘A Ballad of Balin and Pellam’, which was no doubt inspired by Tennyson and William Morris.

But withal, there is no doubt that Boothroyd has fused these influences into a set of vignettes uniquely his own. The English Catalogue of Books for 1913, which listed all UK publications, tells us that there were about 400 new books of poetry or verse drama issued that year. They included Cromwell and Other Poems by John Drinkwater; D.H. Lawrence’s Love Poems and Others; and The Wine-Press, A Tale of War by Alfred Noyes. The prevailing taste was for weighty, solemn, portentous, usually very long blank verses. Boothroyd’s book could hardly have been more different.

The verses evoke strange creatures, such as a mole that eats live coals, and a cockatrice that prefers to be fed on purple spice. They (the verses) are infused with the exotic lyricism of the Yellow Nineties. But the wonderful fancy of Norman Boothroyd’s work also has an undertone of gentle melancholy and the shadows of the macabre. Here is the beginning of ‘Uthorion’:

Now have I built a choice pavilion:

A wondrous place in shining gold arrayed—

With amber windows, and great doors inlaid

With silver, sandal, and vermillion;

And in a room whose floors Sicilian

Are swept by tapestries of every shade

From palest amethyst to darkest jade:

There do I keep my tame Grizilion.

Apes and Peacocks has a rather rueful ‘Publisher’s Note’ at the front which says that the only artist capable of illustrating the pieces, which ‘suggest pictures strange and wonderful’, ‘has failed to meet the demand. The effort has reduced him to despair’. This was presumably W. Sandys, who did provide a frontispiece (only) in, unsurprisingly, a rather Beardsley-esque manner. However, says the publisher, they have left blank pages where ‘the reader may rise superior to the artist, and be able to illustrate the book himself’, or know an artist who might. ‘In so doing,’ the publisher continues, ‘the reader would, in conjunction with the Author, produce a rare and priceless book’. This is quite a novel idea and I have always hoped to find one such uniquely illustrated copy, but alas none has come to hand: indeed, I have not seen another copy of the book at all, hand-illustrated or otherwise.

There are a few fugitive examples of Norman Boothroyd’s work in periodicals. His poem ‘Le Livre du Mal’ was published in The New Age edited by A.R. Orage (Volume 12, Nov 1912-April 1913), while another poem, ‘The End of the Lonely King’ appeared in The Blue Review (Vol 1, No 2, June 1913), alongside work by James Elroy Flecker, J.D. Beresford and Katherine Mansfield. A further poem, not in either of his books, and discovered by the American scholar Douglas A. Anderson, was ‘Old Women’, published in The Living Age (Boston, 13 February 1915). These contributions suggest Boothroyd was keen to see his work in the avant-garde modernist journals of the day, and possibly he may have mingled with some of the other writers involved in these.

He also made a few prose contributions to periodicals of the time. There was a note by him in Notes and Queries in 1909 under the heading “Matthew Arnold, Shelley, Keats, And The Yew”. This quotes Ovid and Pliny on the custom of female mourners cutting their hair and laying it over the body of the deceased. Among family papers there are also records of two talks he gave, one on ‘The Psychology of Luck’, the other ‘On Nothing’.

Norman Boothroyd’s verses do not convey any autobiographical hints, other than an oblique appreciation of the sort of spirit that might have prompted them. A few poems have landscape features – a hill, a pool – but these are not specific enough to evoke a particular locality as would, say, the rural, out-for-a-ramble pieces of the contemporary Georgian poets. There is one poem, ‘In Lucton Lane (A Rondeau)’, which set me searching for the road in question and finding one in deepest Herefordshire which even now, over a century later, still has something of the ‘drowsy air’ and ‘flower-hung banks’ and ‘languorous days’ and ‘slumbering shadows’ that Boothroyd evokes, so I like to think it was here he haunted on one summer walking tour.

His great-niece, who has researched family history, kindly gave me some biographical details. Norman Boothroyd was born in Holmfirth, Yorkshire in 1883, the first of three sons of Samuel Boothroyd, a woollen mill manager, and his wife Catherine. In the First World War, he was posted as a Temporary 2nd Lieutenant in the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry on 19 December 1916. He later worked chiefly as a burial officer, a grim task in the conditions of the war, and one requiring both strong practical skills and sensitivity. He was commended by his commanding officer for his work here.

His great-niece told me: ‘Norman had quite a distinguished army career in the First World War as an Infantry officer – at Armistice he was made a Lieut. Colonel and organised the clearing up of devastated areas, including the Somme, with special regard to the recovery of bodies and concentration of graves (I’m told a sort of forerunner of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission).’

He lived in Batley, Yorkshire through the early 1920s, and married Gladys Margaret Talbot Critchley (1887-1957) in Batley on 5 June 1920. They had two daughters, Anne and Margaret. He moved to Hatch End, London, sometime later in the 1920s, and later to an address in London SW1, and died in Westminster on 27 January 1958, just over a year after his wife passed away. He was awarded the O.B.E. for his services as a Senior Housing and Planning Officer in the Ministry of Housing and Local Government.

But no further literary work is known after the First World War. Perhaps such fantastical, fanciful work no longer seemed appropriate. Even so, it is still worth noticing and celebrating these strange and wonderful verses of his youth.

With thanks to Ros Hollyer (Norman Boothroyd’s great-niece), Douglas A. Anderson for genealogical information, and David Hilder for information from army records.