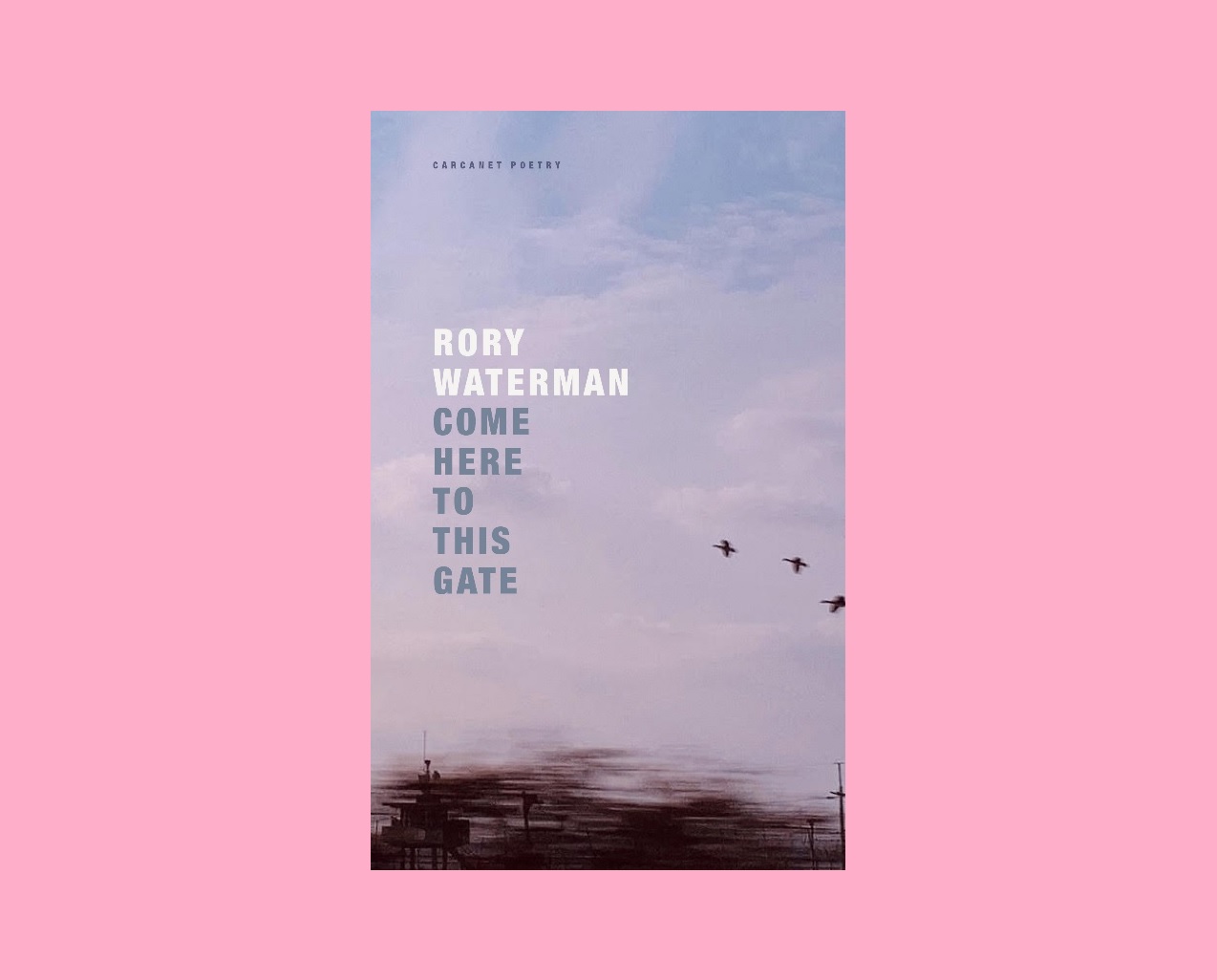

Below is a poem from Rory Waterman’s fourth collection, Come Here to This Gate, published by Carcanet on 25th April.

Until that date, the Carcanet website is offering a 25% discount on the collection, and free UK postage, with the pre-order code RWGATE25 at checkout. There will be an online launch, hosted by Declan Ryan, on the evening of 24th April: tickets here.

Nanny Rutt

a Lincolnshire folk tale, redux

Math Wood is a small plot of trees south of Bourne,

next to McDonald’s and Lidl.

It’s privately owned, full of shot-gun shells, pheasants –

but still, a bit of an idyll,

and Mike lived in Bourne, and Doreen in Northorpe,

a hamlet just south of the wood,

and Mike had got married, and Doreen had too,

and because they were up to no good

they’d meet now and then by the well in the middle,

kiss, fumble, roll on the loam

for a bit, then rush back for vigorous showers

before their spouses got home

from work (someone has to). Now, Math Wood’s well named.

It’s a puzzle, a subset of signs:

square roots, infinities, integers, means,

and fives, sixes, sevens, eights, nines

weaving about on top of a congruence –

all very pretty when light

is streaking through leaves into leaves and leaf-litter.

It’s rather less pretty at night,

but as Doreen set out, the sun splashed each tree,

and blackberries brushed every track,

and squirrels and blackbirds were bobbing about,

and she didn’t think once to head back

till she saw a strange woman reading a book

(The Tenant of Wildfell Hall)

on a log by the scraggle of path. She was filthy,

her face obscured by a shawl,

and she didn’t look up, just twisted her neck

to the spot where Doreen now stood,

deciding to turn or to pass. Then she rasped:

‘I’ve seen you here, up to no good.

That fat little goon gave the clap to his wife,

and you think you’re the one, but you’re not.

You’ll ruin your life.’ She cackled. ‘Take care.’

Was she mad? Her breath smelled like rot,

and a bottle of Buckfast was wedged in her lap.

Yes. Doreen shot, like a rabbit,

round the foul thing, then a bend, then another,

then she tired, decided to sit

and thumbed Mike a message: ‘eva met the old hag? x’.

‘wot? x’. ‘nevamind its not good x’ –

then her battery died as she went to hit send.

Shit. So she sped through the wood

for a few minutes more, and came to the well,

but Mike hadn’t made it there yet.

And half an hour later he still hadn’t come.

It wasn’t like Mike to forget:

this was too new. But soon the wood changed,

the sky going orange then black,

as bats replaced birds and the moon floated in.

She gave up and resolved to head back.

And was it her tears, the sting of rejection,

the dark, or blind fear she’d get caught

if Steve came home early? Whatever it was,

her route was an infinite nought,

or something like that. Then she stopped for a rest

by a little hut covered in ivy.

What on earth was it? She’d not been this way.

Then a shaky voice cried ‘Come to me!’

and she saw the old hag slide out from the door,

the tattered shawl down by her waist,

her arms thrust in front as she ran straight at Doreen,

synapses pulling her face

to a scowl of disdain. That’s the last Doreen saw.

And no, this tale has no redemption.

For that, blame the people of Northorpe or Bourne.

(If you like it, give Rory a mention.)