Julian Stannard

‘You sit/down to put into words your reckoning.’

I don’t read Tim Cumming with any expectation of the anodyne. The title of his latest book (Knuckle, Pitt Street Poetry, 2019) suggests the experience, as ever, will be bracing. ‘The Knuckle End’ – almost the title-poem – considers the poet’s elderly mother whose apparent frugality underscores a poetry of metaphysical acuity where the measurable world co-exists with something out of reach:

My brother and I spooning out seconds, leaving three slices from the knuckle end, her favourite, for tomorrow or the day after, which will come, if less firm in the hand and the mind though the eye is always keen and sees clearly what is and isn’t there.

This yoking together of the concrete and the abstract is emblematic of Cumming’s thirty years or so of writing. I’m going to present [‘Knuckle /End..?’] as a poetic equation.

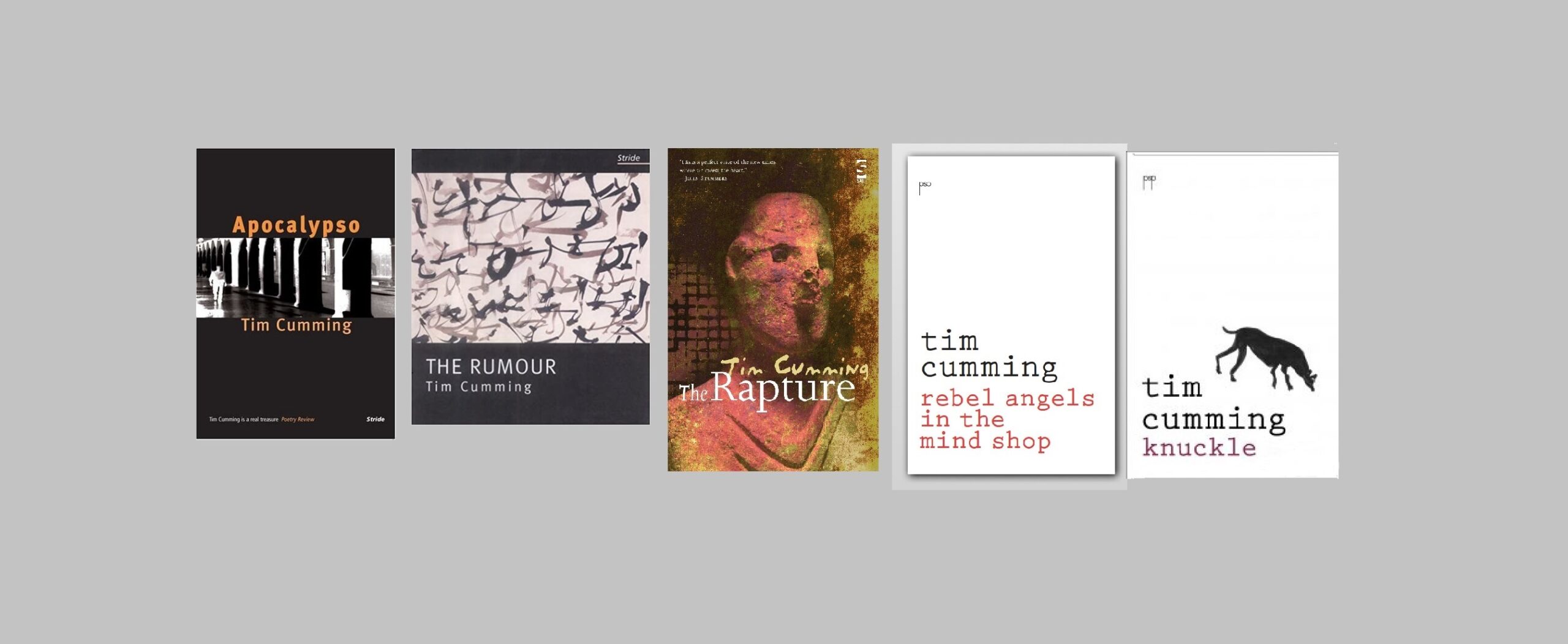

Knuckle joins a list of collections whose very titles demand attention. These include Rebel Angels in the Mind Shop (Pit Street Poetry, 2015), The Rapture (Salt, 2011), The Rumour (Stride, 2004) and Apocalypso (Stride, 1992, 1999). His work has also appeared in numerous anthologies such as Bloodaxe’s Identity Parade. He’s always been conscious of that great cosmological unfolding – ‘Cosmic rays stroke the atmosphere, /../ against the background hiss of creation’ (‘Radio Carbon’) – and the first section of Knuckle is called ‘Other Planets’, where the mundane might be illuminated with star dust, not to mention ‘Ziggy Stardust’ (‘Venus’). Yet his poetry also listens out for that ‘sound / in the distance pushing us forward’. Time’s Winged Chariot, for any poet, is a readily available trope yet Cumming steps away from vague intimations of mortality to give us carefully observed and/or imagined journeys, in this country and across geographical spaces further afield: micro-travelogues, the launching of spacecraft, air travel, public transport including trams. We find in ‘Revellers’, for example, from the Budapest section of his most recent book ‘the 6 tram’s duende/coming in to sleep’ in the small boozy hours, a woman’s voice announcing:

each stop of the way to an almost-empty carriage, as tender as a proposal of marriage, syllables breaking on Belle Epoch ceramics of the inner ear. The tram driver’s face at Kálvin Tér. The door swings open. This is our stop. We get off here.

Difficult to convey the frisson I get from this poem. The late tram rock, the empty carriage, a journey through the night of an ancient city, the point of arrival – ‘This is our stop/ We get off here’ – and this end point, or terminus, is a kind of beginning in that Eliotic sense: ‘What we call the beginning is often the end. / And to make and end is to make a beginning. / The end is where we start from.’ Cumming’s poem plays with slippages of time and place, as if the tram frees itself from the here and now to take on an unexpected chthonic power. The nineteenth century of the Belle Epoch, with its luxurious extravagance, chunters into John Calvin Square, named after the sixteenth-century puritan who believed in predestination. A tram of late-night revellers comes to a halt in the square of the French theologian who preached salvation for the Elect. The last lines of the poem, with no little subtlety, are now weighted with eschatological pressure: ‘The door swings open.’

Ends, evanescence, death, revenants of a kind, resurrections, continuities, non-linear cyclical time: ‘And to make and end is to make a beginning. / The end is where we start from.’ The memorial poem for Ken Smith (1938-2003) from The Rapture is called ‘White Border’ and begins: ‘You were coming back to us, / the long slow climb from the rear / view mirror of your life, plotting / your coordinates to the white / borders of the map.’ It’s a single-block poem, a form much favoured by Cumming. It allows for the organic accumulation of detail, a lineation which quickens and slows, a forward moving run-on energy, the velocity sometimes reined in with touches of end-stopping punctuation. In effect ‘White Border’, like much of Cumming’s poetry, is seared with a poetic voltage. This is a poem about loss and there is palpable pain and disbelief. It gives us snatches of domestic detail, colloquial exchange, memories of Ken Smith, fellow traveller:

I’m looking back and you’re in ` the corner of your living room, plates of Persian chicken and fuck your fucking soup, I want cake and vodka in a tall cold glass.

Smith’s death at the age of sixty-four is inscribed in the act of restless journeying and wraps itself round the story of Lazarus:

I turn back from the main road and the wrong bus, the last train, the missed connections, the wildlife in the sidings. There’s things to talk about. We’re taking the last possible route to where we lay you down under the trees that’ll become you and raise your body out of the stupid box.

Cumming’s poems are not religious but often there’s a religiosity about them and the title of the collection – The Rapture – captures the poet’s ability to move swiftly between quotidian detail and Blakean vistas, as we step out of the known into heightened spheres of ecstatic/abashed possibility.

An earlier poem from Apocalypso – ‘No Smoking, No Dancing’ – seemingly deals with death more directly if not without Cumming’s bracing humour: ‘Feeling for your matches you follow the coffin in sensible shoes / as professional mourners gather at the grave and one of them / coughs a smoker’s cough.’ Yet the familiarity, more or less, of this graveside scene is knocked into another orbit mid-poem as the cigarette smoking mourner succumbs to ‘odd thoughts’ which ‘move like alien aircraft move, / without any logic or earthly origin.’ Cumming returns to this idea in Knuckle, some twenty or so years later. ‘Radio Carbon’, arguably, sketches out the contours of a nascent manifesto:

We bury our dead in the ground and listen, the gauze curtain of cosmic forces which calibrate a human hair rippling like a field of wheat through air, sackcloth through the ether - another medium we don’t believe in anymore.

Such lines raise the hairs on the back of your neck and herald Cumming as a modern-day seer. His creative visions and ‘unfathomable longings’ (‘Sehnsucht’) bridge the reality of ‘Kilburn High Road’ and ‘Wandsworth’ and ‘Vauxhall’ and ‘Ladbroke Grove’, that which is ‘familiar’ (‘The City Inside’), with a world shot through with an invisible ‘deified’ energy, a world beyond us and within us, which has some genealogical kinship with Wordsworth’s ‘We see into the life of things’ and Ezra Pound’s ‘The Return’ (‘Gods of the wingèd shoe! / With them the silver hounds, / sniffing the trace of air!’).

These are Cumming’s hunting grounds from Apocalypso onwards, that late twentieth-century harbinger of ‘Strange Days’ and ‘Strange Music’ and strange alignments, a jazzed up recalibration of Keats’ Negative Capability. In The Rumour we come across the poem ‘Space’:

In her last months of pregnancy she saw with telescopic vision. She’d sit up in bed surveying the vastness of space. She rarely left the house.

A contemporary take on Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space perhaps? The French philosopher explored the interiorities of the house, the particularities of rooms, cellars, attics, corners, cupboards, drawers, nests. He introduces the idea of Topoanalysis, the psychological examination of the sites and micro-spaces of the house, the most intimate of spaces, which ‘protects the daydreamer’ and reveals the soul. In Cumming’s poem the unfolding of the cosmos is folded into the pregnant woman, a miraculous conception if not an immaculate one. We are told: ‘She was tired of the words/that people used for everything/ but the long comforting vowel/of space was everywhere and nowhere, / travelling at invisible speeds /from the first impossible second to the last / as present and the past / that comes into your life’. Difficult, again, not to reach for the long-sighted Eliot – ‘In my beginning is my end /…/ a time for the wind to break the loosened pane / And to shake the wainscot where the field-mouse trots’. In ‘Space’ Cumming folds the infinite, the unimaginably immense and the bewilderingly abstract into the somatic experience of childbearing, another type of Bachelardian nest. Beginnings and ends slip their binaries, the unknown is made flesh. We are children of the Big Bang …Yet Cumming doesn’t allow any simple surrender to this head-spinning immensity. The poem injects a dystopian note, post-Fukuyama:

She thought that space would come from afar but it was inside her all the time, the voice in her head like the voice of a secret government, the new world order.

‘Now, Voyager’ is from Rebel Angels in the Mind Shop and begins at the beginning, 1977 – a time before our time of instant connectivity – and the poem creates its own cascading journey of historical allusions and synaptic vibrations. The poem starts: ‘Launched in 1977, Voyager One / has now left the solar system’. Yet the ‘computerised extras mingl[ing] with super cool hydrogen atoms’ throw the poem into other temporal realities as if the propulsion of Voyager One had an alternative/simultaneous reverse pedal, the past in the present and the future, as we move from ‘the Rivoli musical hall, 1593,’ to ‘the Pleasure Gardens of Vauxhall’, the ‘Mayflower pilgrims / rolling over the waves in the ship’s clock’, a baby’s cry ‘shaking into an old blues / singer’s voice on Magazine Street, 1920s / New Orleans.’ The poem, quickening, pulls off an audacious riff. Armstrong is now musician and astronaut, and the journey is unconstrained by teleological certainty:

Armstrong’s trumpet sailing by freight, smoking in a barrel at Brixton Academy, 1931, gathering up the ribbon of a tune and wrapping it round a gold disc in the fuselage of Voyager One as it passes through the Oort Cloud…

And the knuckle? In his quest for quiddity and luminous detail Ezra Pound argued in the Imagist Manifesto (1912): ‘We believe that poetry should render particulars exactly and not deal in vague generalities, however magnificent and sonorous. It is for this reason that we oppose the cosmic poet, who seems to us to shirk the real difficulties of his art.’ Pound wasn’t hidebound by this early Manifesto but he rarely ignored this requirement for imagistic intensity even if the Cantos are charged variously with wider reverberations, cosmic or otherwise. Cumming is a cosmic poet who holds onto the knuckle. Any cosmic vagary, any futuristic speculation, any rolling out of the marvelous, any time travel into the past is grounded in names, street names, named cities, dates and physical realities or what Donald Davie called ‘the reek of the human’. It’s this fusion of the physical with the metaphysical which characterizes Cumming’s poetic. If you wrap your lips around the knuckle your senses are overrun by consonants and the unembellished which both temper and somehow clarify ‘the long comforting vowel/of space’ and those ‘sub atomic collisions / of particles under tremendous pressure – ’ (‘Earshot’). The hand closes, the hand opens; Knuckle reveals ‘one thing held inside another’ (’Passenger’), a creative friction where the short-lined single-block poems enact containment as well as transcendence. In ‘The Knuckles’, from The Rumour, we learn that an old friend is returning from the east with ‘the knuckles of a Buddhist saint / wrapped inside a handkerchief’. Although the knuckles are ‘destined / for a centre in Berkshire’ he turned back ‘at the last minute / and kept them, shook them / like dice, felt lucky for ages.’ The knuckle end, as the poet’s mother knows, is the sweetest part.

Cumming plays with register and tone; the heightened, the sententious are qualified by the colloquial and the demotic. In a preface to Rebel Angels in the Mind Shop the poet bends to tie his laces and splits an old pair of Levis. He asks: ‘Could I get away with going to work with my arse hanging out?’ He tries another pair, same result: ‘What a raggedy arsed bastard and me at my age …’ In pursuit of new jeans he chances across Robertson Davies’ The Rebel Angels (1981) in the Mind shop – the charity shop – and later, now in the esoteric bookshop Treadwells, near the medieval section where the Confession of Isobel Gowdie is ‘sticking out from the shelf like a rude tongue’, he spots Kingsley Palmer’s Oral Folk Tales of Wessex (1973). An irreverential shimmy from arse-bearing jeans to witchcraft and folklore, this latter title Hardyesque. This is an English vignette with a splash of Scottish diablerie, a touch of medieval slapstick, and it’s worth noting how Cumming’s travelling international poetic aligns itself with English place and English mythology.

Cumming is a painter and film maker too. As a painter / watercolourist he gives us views of Dorset, his own Wessex, the county in which he was brought up, as well as vistas from further afield, Morocco and Italy for example. Etruscan Miniatures (Pitt Street Poetry, 2012) is a pocket-sized volumetto which combines paintings – ‘field paintings’ – and poetry composed in Umbria. This miniaturist art work, with its vivid colour, is an example of how the poet-painter plays with the lens, alternating and conflating, as we see at the end of this essay, between the panoramic and the intricately detailed, namely ‘widescreen and close up.’

Cumming’s documentary Hawkwind: Do Not Panic (2007) is worth watching. It’s not without Spinal Tap moments of hilarity though Hawkwind ultimately defies satire by its longevity, disunity and supreme weirdness as the proto-Punk band of multiple reincarnations. Several musicians speak to camera (some fifty musicians passing through the band in thirty years) remembering free concerts and an acid-dropping psychedelic culture as well as that strobing metal/trance/space rock inspired, inter alia, by the science fiction of Michael Moorcock and for a period galvanized by the poet-singer-songwriter Robert Calvert the ‘bipolar heart of the band’. If American flower power was making its mark in the 1960s Hawkwind was a quintessentially English creation whose beating heart was Ladbroke Grove, not San Francisco.

Cumming’s engagement with English counterculture is not incompatible with American poetics. His poetry is inflected not so much by Beat-style protest but rather more by that generous aleatory freewheeling Black Mountain spirit of Olson, Creeley and co whose manifesto included the advice: ‘One Perception Must Immediately And Directly Lead To Further Perception’. If Larkin hankered after Sydney Bechet, Cumming’s lodestar is the Picasso of Jazz. He writes: ‘If you haven’t got your ding, the hidden thread running through the underlay, then all you’ve got is technique… As Miles Davis once said, you got to have your ding’.

Knuckle ends with ‘The City Inside’. It’s a mind-splitting, pulse-quickening meta-poem. It’s a tour de force. It begins casually enough, jaunty with rhyme: ‘It was the end of the late shift. / I’d logged off, queued for the lift, / took a side door onto the street.’ This side door is a portal onto a filmic, sometimes recognizable London of Russel Square and Soho and Willesden et al yet it is also a city where ‘legions / of the dead’ are ‘rising up through the street’, an image both terrifying and somehow strangely comforting, as if an army of psychopomps were on the move. The weight of the past leans on the present: ‘Schoolboys with blades / hidden up their sleeves fan / the flames from here on down / to the medieval city flooded/with cut-up move memorabilia. / There’d been a landslip between millennia –/ minstrelsy, mud and cyclical time, / the clamour of curfew bells, / flint knappers flaying a beast.’ The city is full of brooding violence: ‘Amphetamine Billy’ and ‘lesbian gangsters in leather and lace’ and – another man who bends to tie laces, where knuckle has been replaced by pig gristle – ‘the sharp / raw nerve of the London mob flaming /in a lone drinker’s jaw …./ stooping / to tie his laces in the gutter, / pig gristle snacks and a pliable / young Victorian whore to wallow / in’.

The poem is hallucinatory, Rimbaudian, spectral (a premonition, inter alia, of lockdown London and residual memories of plagues past). The poem is exhilaratingly apocalyptic, as it re-imagines a wasteland of falling towers and falling bridges and collapsing streets: ‘Denmark street is falling down/falling down falling down’, where the London Underground is now the underworld, or even James Thomson’s The City of Dreadful Night, through which the self-mythologizing (Orphic) poet travels ‘using paper, scissors and pen.’

The job of the poet is to bear witness, to make a mark in the ledger, and the speaker gathers the ‘world’s inks’ into ‘a sorcerer’s gait,/pooling words/on a printer’s slate,’ embracing the numinous and the profane. At the beginning of the poem the poet says: ‘They say that it is written, / so who was writing this, I wondered, / pulling at the nearest pages.’ Now he pushes ‘through the door / of a bookshop opposite the temple,’ in ‘the company of absent friends’ and finds ‘papers stuffed in every crack. / I recognized the writing. /It was mine, the bottom line, / everything I’d left behind.’

Cumming is a psycho-geographer slipping between the coordinates of time: ‘One night I was walking on the river, / full moon, low tide, thin ice, /… /I’d walked for hours, it seemed, / footfalls between centuries, / in London’s diorama / glimpses of an older city rising/and falling roughly above the time/ and tide line of shop fronts.’ At the end of the poem he pushes ‘through the door / of the Rising Sun and writes[s]/[his] way to the back of the pub, out /the side door into an alley.’ He’s looking for recognizable faces as the city, with Biblical fiat, is now ‘folding us into its palm.’ The hand opens and the hand closes, with its keyboard of knuckles. The Leviathan city shucks off the poet’s ego and writes him into ‘the book of London’, that great palimpsest, a book of judgement, with its ‘spidery writing’:

High above the city, low clouds envelops all human life, the way down crowded with mythological life form moving through us like wind through grass, Priapus and Zeus trailing a round Soho after lunchtime rounds at the Spanish Bar, batting off mayflies, going with the flow towards Covent Garden in the London of Blake and Defoe, and soon they are lost to us; we follow after them, one by one, dissolving as if into a solution, one part in sixteen million, your name and your account to be taken. You sit down to put into words your reckoning.