Mark Valentine

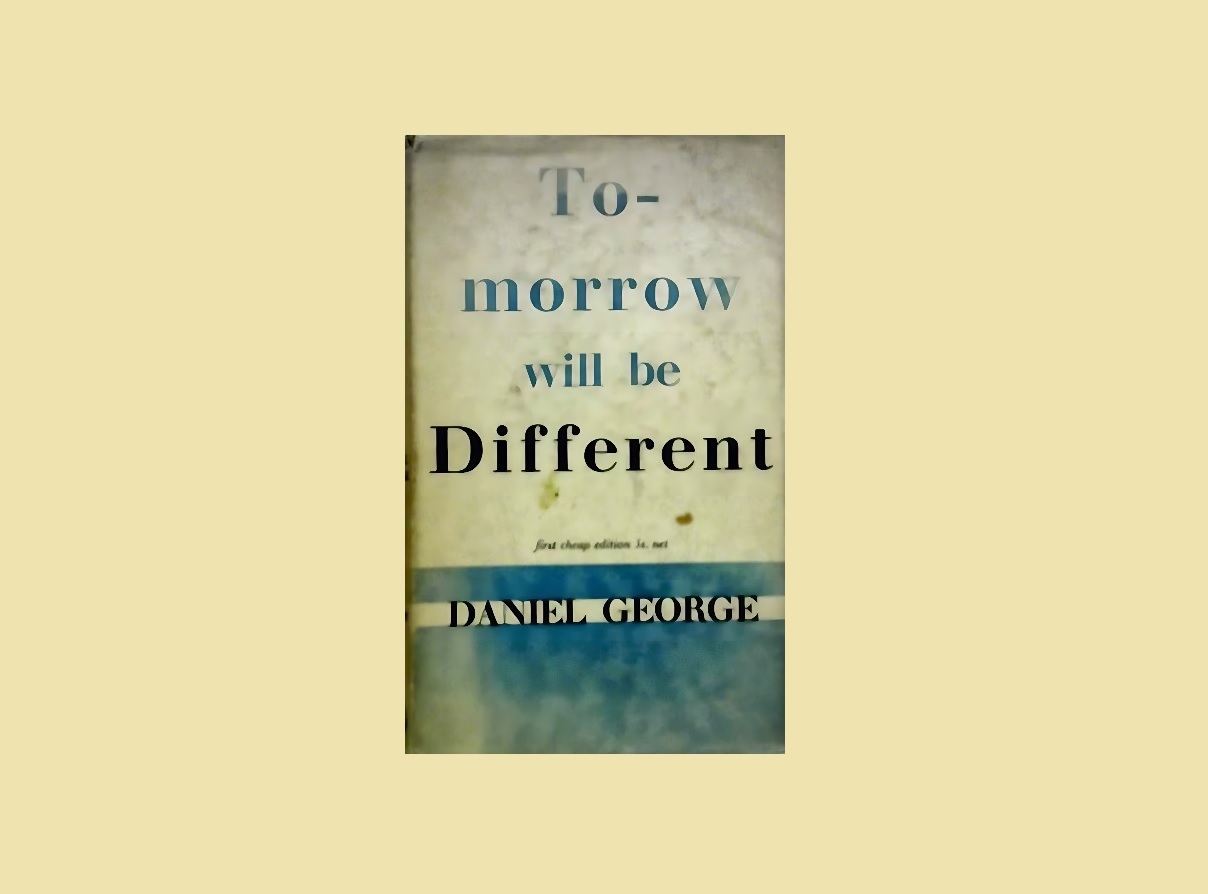

Daniel George (1890-1967) was the author of To-morrow Will Be Different (1932), a book-length narrative poem about a day in his life, getting up, bathing and shaving, going for a walk with friends, visiting the pub, then meeting at a cottage for tea. It is, as the epigraph quotation from Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Notebooks suggests: “The journal of a human heart for a single day in ordinary circumstances. The lights and shadows that flit across it; its internal vicissitudes.”

To-morrow Will Be Different follows the narrator’s thoughts and experiences in detail, in a “stream of consciousness”, and is written in an informal, engaging, free-verse style, so that the reader feels they are sharing the immediacy of the casual passing moment. Even those constitutionally averse to poetry may still warm to it, as it can simply be read as the fascinating journal entry of an attentive, alert, frank individual.

It is an attractive experiment, and although the poet acknowledges his debt to Joyce and Eliot, this modernist style is used in the service of the Georgian poets’ interest in the countryside, gentle pleasures and good-fellowship: an odd combination, but it works. It is rather as if Edward Thomas had survived the war to read ‘The Waste Land’ and adjusted his style, though not his subject matter, accordingly. “Reveals with disarming candour the reactions of an agreeable and typically modern personality,’ said the Times Literary Supplement. Clemence Dane described it as “growing fine, growing silly, ambling, trotting, breaking off suddenly, resuming cheerfully, loquacious, quotacious, funny, tragic, coarse”.

The scene in the cottage where the walkers have been invited for tea is a particularly keen depiction of an English social occasion, with the awkward balancing of cup, saucer and sandwich plate on knees, the overcrowded room making any manoeuvre a matter of acrobatic balance, the rise and fall of inconsequent chatter, the calling out of crossword clues for party amusement, the duties to the host and the expression of suitable but not over-effusive gratitude:

Mary with tray.

Very soubrettish.

Tea, coffee, cocoa, or ovaltine?

I will pass cups.

Mrs. Duncan avec sandwiches.

Coffee for you? –

Here, take this. –

Sandwich? –

I nearly fell over the rug then.

Put away that silly paper, and eat.

The author of this bravura work did not publish much other poetry, simply a few privately produced pamphlets: Lunch, A Conversation Piece (1933); Holiday (1934); Roughage (Warlingham: Samson Press, 1935) and Pictures and Rhymes (from the same press, 1936, with pictures by Gwenda Morgan). He was, however, a busy literary figure in other spheres.

‘Daniel George’ was the pen-name of Daniel George Bunting. According to the archives of the University of Exeter, he “was born on the Isle of Portland, the son of a naval man. In the First World War he served with the Queen’s Westminster Rifles, after the war he worked for an engineering firm in London with whom he became general manager. In 1940 George became a reader for publisher Jonathan Cape, a position he held until his retirement in 1963… He died in London in 1967.”

To-morrow will be Different includes frequent flashbacks to his service in the trenches as a private, the squalid conditions, and the friends and comrades he lost there. He cannot keep the war long out of his thoughts, and even on a quiet country walk with friends the slightest reminder, such as a muddy field path suggesting the trenches, revives it again:

I ought to get myself psyched.

The war poisoned my mind.

[. . .]

Still, as the Psalmist says,

A dirty mind is a continual feast.

Sweet black mud iridescent with dung,

Mud the consistency of the dregs of cocoa.

I got stuck in the mud near Zillebeke.

Cut that right out!

Why don’t you write a war book, one of his friends asks, but he knows that he can’t.

George’s first literary work seems to have been editing a selection of Recollections of Charles Lamb (Elkin, Mathews and Marrot, 1927). He became the Chief Reader for Cape from 1945, and gave wireless talks on ‘Books and Authors’ for the BBC Light Programme from around 1947. He published a book of essays, Lonely Pleasures, in 1954. But he was perhaps most known as the compiler of quirky anthologies full of light-hearted learning informed by wide reading.

He collaborated with Catherine Carswell, now most known for her biography of D. H. Lawrence, The Savage Pilgrimage (1932), on A National Gallery. Being a Collection of English Characters (1933) and The English in Love. A Museum of Illustrative Verse and Prose Pieces from the 14th cent. to the 20th (1934). His other anthologies included:

A Peck of Troubles; or, an Anatomy of woe, in which are collected by Daniel George many hundreds of examples of those chagrins and mortifications which have beset, still beset, and ever will beset the human race, etc. (1936)

Pick and Choose: a Gammautry Composed… for the Diversion and Solace of the Ruminant Reader (1936)

All in a Maze. A collection of prose and verse chronologically arranged by Daniel George, with some assistance from Rose Macaulay (1938)

Alphabetical Order. A gallimaufry. Containing “An Alphabet of Literary Prejudice,” “Work in Process,” “Pick and Choose,” and “Extracts from my Notebooks” (1949)

The Perpetual Pessimist. An everlasting calendar of gloom and almanac of woe, complete with reference section… Decorations by John Glashan, Edited with Sagittarius i.e. Olga Katzin

George knew and corresponded with T. E. Lawrence, presumably through his position at Cape, and also knew Aleister Crowley, who is mentioned in passing in To-morrow Will be Different. But his poem is not about notables, but rather an affectionate if sometimes wry portrayal of the quirks and foibles of the friends who accompany him on his walk, and an appreciation of the pleasures of the pub and the tea table. In a note to a correspondent accompanying a copy I now have, he says: “Looking at it this morning, quite impersonally, it struck me as likely to amuse you here & there…”, a modest enough claim.

To-morrow Will Be Different does not seem to have been a notable seller. In an inscribed copy offered for sale, George mentions ruefully: “[P]urchased/by me in Praed St. All booksellers/can be beaten down: I got it for a/shilling. Gratefully/Daniel George.”

This essay is the latest in a series for Wild Court by Mark Valentine on obscure publications and poets lost to posterity, and rare books. The series can be found here.