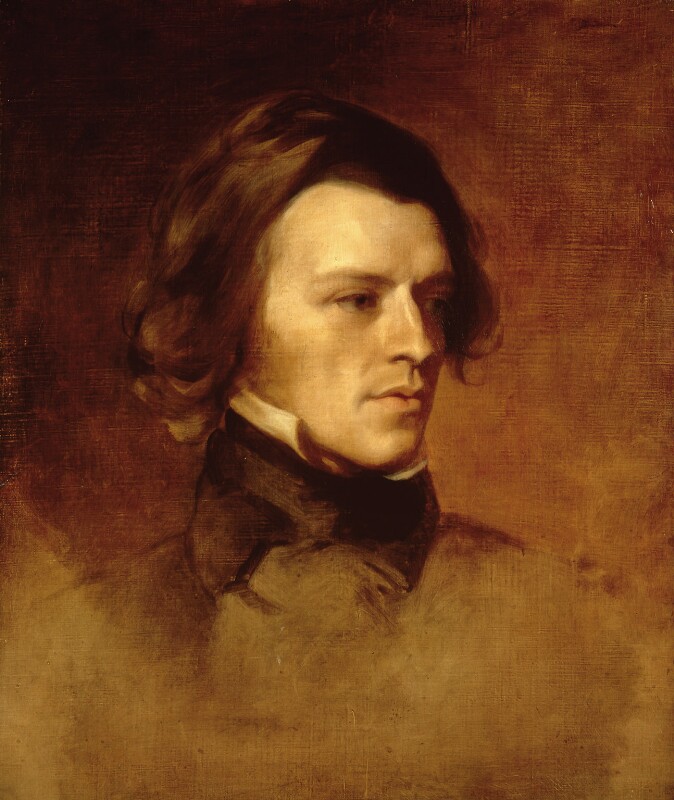

Alfred, Lord Tennyson by Samuel Laurence, and Sir Edward Burne-Jones

oil on canvas, circa 1840 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Lily Searstone

Tennyson’s elegiac phenomenon of In Memoriam situates itself in nineteenth century literature as one of the first and most profound introspections of the ‘deepest needs and perplexities of humanity’[i]. In Memoriam’s contemplations of death and mourning are bound up with the poet’s memories of his deceased companion, with every recollection coloured by the imposition of a radically changing society. Tennyson was a highly progressive figure, with many attesting to his forward thinking[ii] reconceptualisations of what would seem to be stationary principles, such as death and religion that lend themselves to rigid Victorian convention. However, the rising popularity of Spiritualism around the time In Memoriam was published[iii] in 1850[iv] was symptomatic of the religious confusion instigated by the threat of those such as Darwin and ‘positivist science.’[v] The poem’s immediate subject of the deceased Arthur Hallam becomes a catalyst for Tennyson’s deeper contemplations into the nature of endings as an indefinite concept. This preoccupation with endings is a defining feature of In Memoriam, as the poet ‘seeks to eschew the conclusiveness and finality’[vi] that accompanies death. The elegies principle mechanism of mourning is this envisionment[vii] of death as not the end of life, but an extension of it. In the same way that Tennyson immortalised Hallam in his In Memoriam, his son not only perpetuated his father’s memory, but also his literary doctrine. Central to this essay is the notion that the writing process served both as a mechanism of memory and mourning by refusing to forget and thus, keeping both the joy and pain of Hallam’s deathly image alive for generations to come. It is also important to consider not only the poet’s grief, but how Victorian convention with regards to gender and religious belief[viii] had an impact on methods of memory and mourning in the nineteenth-century.

In Memoriam’s confrontation of orthodox Christianity and faith is firmly embedded within the poet’s personal process of grief, with a sobering refocusing of the society in which the elegy contributed to. Scholars of Tennyson’s work have debated the extent to which the poet acclaims his Christian faith as an integral guide of mourning and acceptance in the face of death. The introduction of the poem in particular, is packed with a religious resonance: “Strong Son of God, immortal Love / Whom we, that have not seen thy face, By faith, and faith alone, embrace, / Believing where we cannot prove.”[ix] Tennyson’s beginning position in prayer is reminiscent of a devoutly religious man, however I am more inclined to agree with Howard in imagining a looser periphery of religious intent at this stage in the poem. Tennyson’s belief system, I would suggest, is more rooted in the nature of “immortal love” (Prol.) as the ‘predominant divine attribute that Tennyson associates with Jesus Christ’[x] and his deceased companion. The poet’s personification of love as a principle virtue carries pseudo-religious connotations by attesting love to be the ultimate component of faith. His internal supplicatory monologue, however, suggests the vital function of mainstream religion is regressing, finding purpose in the things “where we [science] cannot prove” (Prol.), and thus hinting at the increasing redundancy of orthodox doctrine in the face of a technological revolution. As the poem progresses as with Tennyson’s grief, it is the power of resurrection, I believe to be the key religious foundation of both In Memoriam and Tennyson’s personal religion; as the poet breathes new life into his deceased companion through the power of words. This strong undercurrent of resurrection can certainly be perceived as a reaction to the increasing visibility of ‘public mourning rituals affirming death… and the finality of loss.’[xi] We know that Tennyson rejected the formal performative aspects of mourning as he decided upon not attending Hallam’s funeral.[xii] Tennyson’s simultaneous, paradoxical closeness and distance from death heightens the sharp fluctuations of emotional feeling attached to grief. However, graves were the primary visible markers of the Victorian obsession with the materiality of death and ‘keeping alive the memory of the dead person in a particularly vivid manner.’[xiii] Tennyson’s In Memoriam almost became a physical site of mourning in itself, as lines from the poem were inscribed on a mass scale on the tombs of the ‘ordinary dead’[xiv]. Furthermore, In Memoriam was in a way sent to the grave not only with Hallam, but as the collective voice of the Victorian dead.

However, at its core, religion in Tennyson’s great elegiac monument functions as an enabler and consolation of grief and memory. Death, as the worst unknown in life pushes society towards a hopeful unknown such as a belief in the divine and a popular concept among writers of the time – the ‘good death’[xv] – commented upon throughout In Memoriam: “‘They rest,’ we said, ‘their sleep is sweet.’” (XXX) It seems as though Tennyson took solace in the ambiguous concepts of Christian doctrine such as the afterlife. Idealising a blissful existence beyond the grave both aligned with institutionalised religion and his personal reluctance to see death as the ultimate end. Nineteenth century historian James Anthony Froude theorised that In Memoriam created a space in literature and society for those who wanted to question ‘the preconceived resolution that the orthodox conclusions must come out true.’[xvi] Although Tennyson’s faith undoubtedly fluctuates in its strength throughout the elegy, the final stanza of the Epilogue encompasses the whole work, and existence itself as “One God, one law, one element, / And one far-off divine element, / To which the whole creation moves.” (Epil.) This could be dually interpreted as a divine governance over both Tennyson’s great works and macrocosmically, the universe itself. Certainly, it is important that we consider the poet’s religious journey as a parallel narrative to his lament of Hallam.

In Memoriam is a deeply personal elaboration of Tennyson’s progressive thought which he related to the masses through publicising his own personal struggles with bereavement. His principle devoutness was to commemorating Hallam’s memory, and secondly to Christ. Lutz pays particularly close attention to the sacralisation of Hallam[xvii] and Tennyson explicitly marks him to be “The man I held as half-divine”. (XIV) In a similar vein to the divine attributes of Christ, for Tennyson, Hallam’s ashes are “sacred dust” (XXI) and “All he said of things divine, / And dear to me as sacred wine / To dying lips is all he said.” (XXXVII) The poet’s visceral fears of forgetting the departed attests to the gravity of loss felt by Tennyson in fixating on the most acute details of Hallam’s person. The innovation of the phonograph transformed death into a tangible component beyond Tennyson’s vivid imaginings. In 1900 Stead wrote in celebration of the introduction of the telephone and phonograph, synthesising that ‘Countless generations mourning the dead have cried with vain longings to hear the sound of the voice that is still… Now the very sound and accent of the living words of the dead whose bodies are in the dust have become the common inheritance of mankind.’[xviii] This concept of a new accessibility to those beyond the grave imparted new meaning on Tennyson’s elegy, the memory of the dead became realised in forms never experienced within traditional society before. Furthermore, conventional mechanisms of memory and mourning were transformed through modernisation, and the new found access to the dead emphasised In Memoriam’s obsessive discussion of grief.

Break, Break, Break is another of Tennyson’s infamous poems in mourning of Hallam, which follows similar stylistic conventions that focus on the physical essence of the dead. The power of Tennyson’s grief is propounded in this poem, as the force of natural phenomena encompasses the chaotic and heavy-weighing burden of what it is to grieve in its initial stages : “But O for the touch of a vanish’d hand / And the sound of a voice that is still!”[xix] The poet’s temporal process of both tangible and audible grief ‘summons Hallam into being, through a sheer force of longing’[xx] by refusing to give Hallam’s mortal soul over to death. An intimate sense of loss within Tennyson’s works upholds the organic nature of In Memoriam, as his relation of personal experience is ‘but the voice of the human race speaking through him’[xxi] as the poet’s meditations diffuse the ‘great questions of philosophy and religion that rise out of the experience of bereavement’[xxii] through society. Scholarly debate has seen the centrality of the ‘body’ fade; however, I would align with Lutz’s insistence of the mortal, and lost body[xxiii] as Tennyson’s key mechanism of accessing the dead in his writing. The poet’s most intense grief, is felt in his desperate cries of “Be near me” (L), which frames the four consecutive stanzas in which Tennyson most ferociously yearns for the physical closeness of his friend, the absence of which makes his “nerves prick /… and the heart sick.” (L) This severe reaction of the living body merely due to the imaginings of Hallam’s dead remains drives the extremity of Tennyson’s aching for his companion. In Memoriam most acutely focuses on the unique anatomy of the person: the hands. Tennyson ‘mentions Arthur’s hands ten times in the poem’. However, the poet is importantly referring to the “hands of faith” (LV) on occasion, as well as those of Hallam as he wishes for him to “Reach out dead hands to comfort me”. (LXXX) Once again, the poet draws comparison between the attributes of Hallam and Christ, as he uses In Memoriam to deify the “gracious memory” of his being.

By extension of immortalising Hallam’s physicality and human soul, Tennyson finds comfort in the process of reincarnation in its most primitive form, quite literally rooting him in the earth’s material: “Where he is English earth is laid, / And from his ashes may be made / The violet of his native land.” (XVIII) This reconceptualisation of Hallam’s corpse may indicate a turning point in Tennyson’s mourning, as he recognises the inevitability of Hallam’s remains decomposing into a form other than his mortal self. However, the poet’s unrelenting refusal to accept a point of termination maintains this surrender to bereavement. Instead, Tennyson desires to create tangible life out of death by the roots of the native violet ‘clinging to Hallam’s bones to keep him local [so]… even the plants partake of his divinity’[xxiv] through this process of regeneration. This almost Spiritualist approach implies that the ‘existence and nature of God could be inferred from natural phenomena’[xxv] if it is to be the case that Hallam’s spirit can in some capacity live on through another vessel.

The intense tangibility of Hallam’s ghost alongside Tennyson’s belief of death to be a temporary state reveals the forces of memory and mourning to be inextricably bound. In Memoriam is in this way characteristic of elegy[xxvi], with its loaded narrative of a reluctance to accept termination of life and legacy which was stripped from Hallam prematurely. Nature’s order is warped in Tennyson’s moonlit reimagining of Hallam’s death to be his own: “When on my bed the moonlight falls, / I know that in thy place of rest / By that broad water of the west, / There comes a glory on the walls.” (LXVII) The morbid contemplations of death within the parameters of Tennyson’s living place of rest illustrates death to be an almost-achieved state of the living. Hayward remarks this compliment of death to ‘assure a continuity of earthly companionships into the next life.’[xxvii] Therefore, to imagine a reunification, Tennyson inevitably lives partially in the realm of the dead alongside Hallam. Such reluctance is embedded within not only the narrative of In Memoriam and Tennyson’s grief, but within his son’s own contemplation of the late poet’s death in his Memoir[xxviii] to his father. Hallam immortalises Tennyson as a ‘figure of breathing marble… reaffirming a sense that Tennyson remains suspended in a state of eternal process: passing.’[xxix] This constant movement leads on from the end of In Memoriam which ends on the line: “And one far-off divine event, / To which the whole creation moves.”(Epil.) In Memoriam as a ‘creation pictured in a state of process’ in some ways provides a hopeful premise that there is a life worth living after the death of a loved companion. Although, the circularities of the poem’s structure and the poet’s process of mourning keeps the poem in a state of perpetual grief despite the eventual acceptance of Hallam’s death towards the end of the poem. Hallam Tennyson’s similar refusal to accept the finality of death is perhaps an example of how death can productively function as an extension of life. Hallam’s personal recollections and interpretations of In Memoriam[xxx] not only strengthens Tennyson’s legacy, but directly references his work through continued visions of the reanimation of the dead: “I think once more he seems to die.”(C) Hallam’s continuations of stylistic and thematic tropes within his father’s works contributes significantly to our modern day reading of In Memoriam, as the ‘tyranny of time’[xxxi] is manipulated at the will of both writers in vain attempts to force the continued revival of the dead.

In Memoriam’s cyclical movement and transitionary structure is rooted within the poet’s relentless obsession with reimagining Hallam’s life and death within an unending cycle. Tennyson’s disillusionment with death is reflected primarily in his mental circulations, however the idle descriptions of his own physical mobility alert the reader to a numb self-awareness that Tennyson carries through much of the poem as a sign of his grief. In two consecutive stanzas the poet refers to his jaded wonderings, as he “loiter’d in the master’s field” (XXXVII) and later remarks that “With weary steps I loiter on”. (XXXVIII) This repetition of the same trance-like motion slows the overall pace of the poem itself, and draws even sharper attention to the grief that Tennyson imposes upon himself by reliving Hallam’s death on a perpetual cycle. Hayward characterises In Memoriam as a ‘constant effort of recovery’[xxxii], however I would reinforce the notion of Tennyson’s constant efforts to grieve and prolong his mourning rather than aiming at recovery. The poet is more concerned with the recovery of his lost companion through his writings, and Tennyson’s eventual coming to peace with death, I would argue is more of an unintended consequence of his literary monumentalisation of Hallam. This populist so called ‘death culture’[xxxiii] that In Memoriam contributed to reframed past, present and future mechanisms of mourning convention by disregarding society’s expectations. Jalland remarks that ‘Victorian society encouraged females to work through their grief, while males were expected to return to public duties far more rapidly.’[xxxiv] Tennyson instead made it his public duty and life’s mission to mourn the death of his friend and figuratively enshrine his memory. Consequently, the poem speaks to revolutionise the rigid standards of society that allotted a finite amount of time to grieve. Further on the principle of motion and memory, Tennyson’s concern with ‘consistency and changeability’[xxxv] enables the poem to function as a mechanism of memory in itself. Its retrospective circling’s construct In Memoriam’s structural narrative as a ‘measure of change and at other times promotes and impression of consistency.’[xxxvi] Perhaps, the best example of this comes from some of the most profoundly impassioned lines of the great elegy: “Behold the man that loved and lost”. (I) One of Tennyson’s most famed introspections is revisited twice more throughout the poem, indicating the potential for productive grief as he eventualises that: “Tis better to have loved and lost, / Than never to have loved at all.” (XXVII, LXXXV) Through Tennyson’s lense of an eternally changing mind and society, his capability to love is unmoved and with this, the reader is able to identify with the poet’s evolving emotional dialogue.

Physical contact with the dead was not just a literary trope within Tennyson’s In Memoriam, but an increasingly prominent feature of Victorian public life. Within Tennyson scholarship, this has been termed a ‘passion of the past’[xxxvii] which is deeply embedded within descriptions of his poetry and ideology. The Victorians’ immersion within the culture of death ‘made the elegiac mood pervasive in their literature’[xxxviii] as an accompaniment to the palpable markers of death flecking the physical environment. Tennyson’s importance of reimagining deathly scenes into which he can insert Hallam’s ghost was interestingly woven throughout the work of his contemporaries. In Memoriam was flanked by works such Milton’s lament for Lycidias and Gray’s Elegy in a Country Churchyard.[xxxix] The projection of Tennyson’s loss of companionship and provoking discussion of the dead permeated the genre on a fundamental level, as authors of the nineteenth century began to tackle the universal struggles from a theological perspective. However, Genung attests to the superior substance of In Memoriam as going ‘further than conventional elegy in which death is the ultimate end.’[xl]

Memory as the decisive enabler of Tennyson’s mourning was for the unbelievers in Victorian society, the central element in their comprehension of death. Interestingly, Tennyson seems to lean on both religion and memory throughout In Memoriam, as by nature elegy seeks to ‘give permanence to the memory of the mourned, and the grief of the mourner.’[xli] However it is arguable that memory adversely stunts the recovery process, by suffocating Tennyson in his own trauma. Hayward identifies the poet’s ‘cycle of temporary resolve before then sliding back into contemplation of deeper grief.’[xlii] Therefore, although memories are impulsive, and uncontrollable intrusions of the mind I would sanction the fixation on memories of the deceased to be as destructive to the soul as death itself. It is only at the end of In Memoriam that we see any definitive resolve and ‘liberation from the grip of memory’[xliii] as Tennyson embraces the present and looks to the future: “Yet less of sorrow lives in me / For of days of happy commune dead; / Less yearning for the friendship fled, / Than some strong bond which is to be.” (CXVI) Certainly by this point Tennyson had peacefully laid to rest Hallam and his desperate “yearning”[s] for the revival of their companionship, as he is able to celebrate a new union between a different friend and his sister who was initially set to marry the late Arthur Hallam.[xliv] Tennyson’s lighter tone of hope and prospective happiness is symbolic of the ultimate process of the human condition.

Tennyson’s elegiac monument is a brave unfolding of the most intrinsic aspects of mortality and the inevitable re-shaping of societal convention against the rapidly changing backdrop of nineteenth century England. In Memoriam’s direct purpose of the commemoration of Arthur Hallam sends the poet into deeper contemplation of what it is to grieve and keep the memory of the dead alive. Scholarship on Tennyson has predominantly focused on his personal religious values and emotional evolution; however, I believe the poem operates as a tool of society rather than a vain expression of the self. Tennyson’s unapologetic disregard for the rigidly upheld conventions of mourning for the Victorian man, saw the poem develop its own sense of time, creating a space for Tennyson to express both manic desperation and lethargic disillusionment over the course In Memoriam’s seventeen-year[xlv] composition. Time is the integral function of the poem, moving the poet from the absolute reluctance of death in all of its forms to acceptance. As the greatest elegiac work of the nineteenth century, Tennyson’s In Memoriam is a universally recognised reality of “our common grief”. (LXXXV)

[i] Hallam Tennyson, Alfred Lord Tennyson: A Memoir (London: Macmillan, 1897), p. 301.

[ii] Tennyson, Alfred Lord Tennyson: A Memoir, p. 298.

[iii] Deborah Lutz, Relics of Death in Victorian Literature and Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), p. 103.

[iv] Jeffrey Howard, Tennyson’s IN MEMORIAM, <https://doi.org/10.1080/00144940.2010.535466> [accessed 12th November 2019] p. 231.

[v] Daniel Brown, ‘Victorian poetry and science’, in The Cambridge Companion to Victorian Poetry, ed. by Joseph Bristow (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), p. 138.

[vi] Helen Hayward, ‘Tennyson’s endings: In Memoriam and the art of commemoration’ <https://doi-org.eres.qnl.qa/10.1093/english/47.187.1> [accessed 20th November 2019] p.3.

[viii] Pat Jalland, ‘The Consolations of Memory’, in Death in the Victorian Family (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996) p. 287.

[ix] Alfred Tennyson, In Memoriam, <http://www.online-literature.com/donne/718/> Prologue.

[x] Jeffrey Howard, Tennyson’s IN MEMORIAM, <https://doi.org/10.1080/00144940.2010.535466> [accessed 12th November 2019] p. 231.

[xi] Pat Jalland, ‘The Consolations of Memory’, in Death in the Victorian Family (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), p.284.

[xii] Deborah Lutz, Relics of Death in Victorian Literature and Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), p. 118.

[xiii] Pat Jalland, ‘The Consolations of Memory’, in Death in the Victorian Family, p.291.

[xiv] Deborah Lutz, Relics of Death in Victorian Literature and Culture, p.114.

[xv] Deborah Lutz, Relics of Death in Victorian Literature and Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), p. 118.

[xvi] James Anthony Froude, quoted in Lutz, Relics of Death in Victorian Literature and Culture, p.114

[xvii] [xvii] Deborah Lutz, Relics of Death in Victorian Literature and Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), p.120.

[xviii] William Thomas Stead, quoted in Robert Douglas-Fairhurst, Victorian Afterlives: The Shaping of Influence in Nineteenth-Century Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), p.1.

[xix] Alfred Tennyson, Break, Break, Break, <https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45318/break-break-break>, III.

[xx] Helen Hayward, Tennyson’s endings: In Memoriam and the art of commemoration <https://doi-org.eres.qnl.qa/10.1093/english/47.187.1> [accessed 20th November 2019] p.7.

[xxi] Andrew Cecil Bradley, A Commentary on Tennyson’s In Memoriam. 2nd Ed. Rev. ed. (London: Macmillan, 1902), p.1.

[xxii] Henry Van Dyke, Studies in Tennyson (New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1920) p.105.

[xxiii] Deborah Lutz, Relics of Death in Victorian Literature and Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), p. 119.

[xxiv] Deborah Lutz, Relics of Death in Victorian Literature and Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), p. 121.

[xxv] Daniel Brown, ‘Victorian poetry and science’, in The Cambridge Companion to Victorian Poetry, ed. by Joseph Bristow (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), p. 139.

[xxvi] John.F Genung, Tennyson’s In Memoriam: Its Purpose and Its Structure; a Study (Houghton: Mifflin, 1884), p.33.

[xxvii] Helen Hayward, Tennyson’s endings: In Memoriam and the art of commemoration <https://doi-org.eres.qnl.qa/10.1093/english/47.187.1> [accessed 20th November 2019], p.2.

[xxviii] Hallam Tennyson, Alfred Lord Tennyson: A Memoir (London: Macmillan, 1897).

[xxix] Hayward, Tennyson’s endings: In Memoriam and the art of commemoration, p.3.

[xxx] Tennyson, Alfred Lord Tennyson: A Memoir, p.301.

[xxxi] Helen Hayward, Tennyson’s endings: In Memoriam and the art of commemoration <https://doi-org.eres.qnl.qa/10.1093/english/47.187.1> [accessed 20th November 2019] p.3.

[xxxii] Hayward, Tennyson’s endings: In Memoriam and the art of commemoration, p.11.

[xxxiii] Deborah Lutz, Relics of Death in Victorian Literature and Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), p. 103.

[xxxiv] Pat Jalland, ‘The Consolations of Memory’, in Death in the Victorian Family (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996) p. 287.

[xxxv] Helen Hayward, Tennyson’s endings: In Memoriam and the art of commemoration, <https://doi-org.eres.qnl.qa/10.1093/english/47.187.1> [accessed 20th November 2019] p.12.

[xxxvi] Hayward, Tennyson’s endings: In Memoriam and the art of commemoration, p.12.

[xxxvii] Deborah Lutz, Relics of Death in Victorian Literature and Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), p. 115.

[xxxviii] Deborah Lutz, Relics of Death in Victorian Literature and Culture, p.103.

[xxxix] Henry Van Dyke, Studies in Tennyson (New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1920) p.105.

[xl] John.F Genung, Tennyson’s In Memoriam: Its Purpose and Its Structure; a Study (Houghton: Mifflin, 1884), p.36.

[xli] Helen Hayward, Tennyson’s endings: In Memoriam and the art of commemoration <https://doi-org.eres.qnl.qa/10.1093/english/47.187.1> [accessed 20th November 2019] p.7.

[xlii] Hayward, Tennyson’s endings: In Memoriam and the art of commemoration, p.11.

[xliii] Hayward, Tennyson’s endings: In Memoriam and the art of commemoration, p.13.

[xliv] Hayward, Tennyson’s endings: In Memoriam and the art of commemoration, p.13.

[xlv] John.F Genung, Tennyson’s In Memoriam: Its Purpose and Its Structure; a Study (Houghton: Mifflin, 1884), p.17.