Daniel Bennett

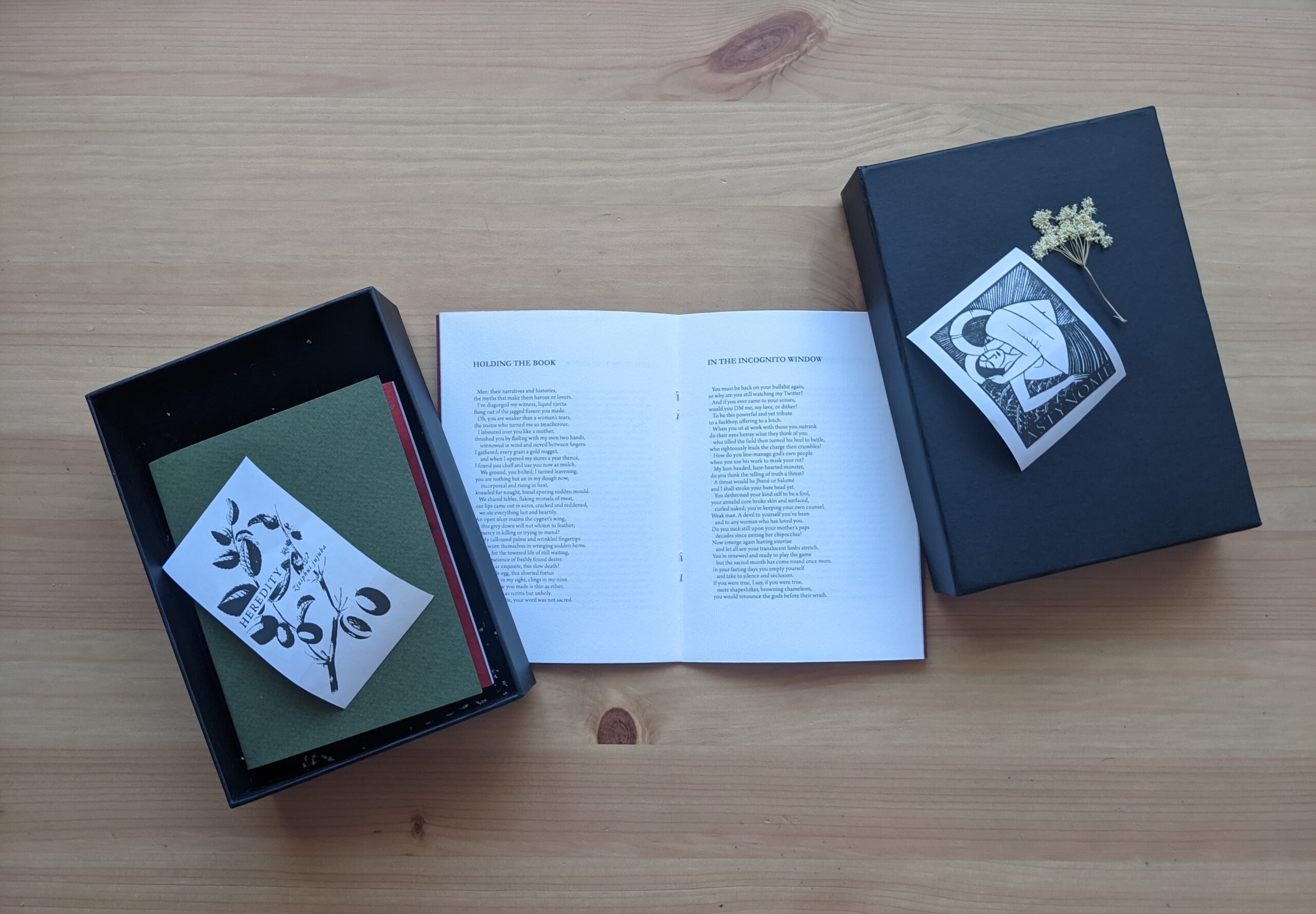

If poetry ever had ‘must have’ purchases, then Naush Sabah’s debut release from Broken Sleep Books proved to be one of these over the summer. The pamphlet, the chapbook, the little magazine: these are as essential a part of the medium of poetry as the poems themselves. Heredity/ASTYNOME is a dream in this regard: a fine object of paper.

A long poem in three parts, Heredity deals with the nuances of family and location associated with a Kashmiri and West Midlands background. Beginning with an epigraph from Thomas Hardy’s poem of the same title, Sabah offers us a meditation on family history, played out through geographical precision. To understand Heredity‘s theme, it’s worth turning to the lines of Hardy’s poem that Sabah omits, which act like negative space to her version:

I am the family face; Flesh perishes, I live on, Projecting trait and trace Through time to times anon, And leaping from place to place Over oblivion.

The poems offer us the realities of this ‘leaping from place to place’ from the start, contrasting the jujube trees of the poet’s mother’s childhood— the ‘green and green and green’ of Chakswari— with the poet’s English childhood, (‘The fallow field/ on Grace Road/ is my childhood wilderness’). The drive for an achievable landscape is echoed in the form of the poems, the thin, long stanzas arranged copse-like across the pages. ‘To learn the words of poetry/ because a poem should / always have trees in it’, Sabah asserts at one point, channelling the Mary Oliver poem ‘Singapore’.

The poem becomes a study in the blurring of geographies, and locations, driven by the semantic desire ‘to know the names of all the greens.’ Green is coded into an easy sense of English identity— think of the way the Tories rebranded themselves after the wilderness years— and Blake’s ‘Green and pleasant land’ has long been co-opted by a sense of sporting nationalism. Sabah seems intent on unpicking and rebuilding our established sense of landscape through a restless itemisation of particular shades of green, which brings to mind the experimental film maker Stan Brakhage’s observation, ‘How many colours are there in a field of grass to the crawling baby unaware of ‘green’?’ ‘A brassy flazen-marbled green … A dewy glinting, shamrock green…a slithy, keeled iridescent green’: as the refrains build, we are offered the sense that through the reclamation and definition of place, a sense of identity will be achieved:

Left, trenchfooted like bare roots,

pardesi to everyone

and everywhere, foreign

to Ammi and Abu

and Nanni and Aunty,

to Chacha in Mirpur,

to the Irish cousins in London,

to the Kashmiri cousins in Yorkshire,

to my siblings, separated

by thin walls and few years.

While the work in Heredity is focussed and mediative, the companion volume ASTYNOME is more immediate and direct, the change in tone announcing itself from the first line, ‘Everyone is fucking the next person’. A short suite of seven poems on the theme of love and its associated frustrations, ASTYNOME takes as its epigraph lines from The Testament of Cresseid by Robert Henrysoun. The title of the work reclaims the accurate name of the character from The Iliad known by the patronymic Chryseis, the origin for the character of Cressida in medieval literature, and the historical trap of women being defined by men is the main theme of these poems:

Men: their narratives and histories, the myths that make them heroes or lovers

('Holding The Book')

If Heredity charges itself through its definition of spaces, then ASTYNOME feels like work scrawled on closing-in walls. ‘ …In slants/ of light at my kitchen faucet I think / I need to cut my nails today, I need to thread my lip.’ The Legitimate Snack imprint of Broken Sleep Books is there to provide ‘poetry mixtapes – works by poets in between releases, showcasing their style and current work.’ Given the remit of the imprint, it’s not impossible that the poems in ASTYNOME were composed during lockdown (‘Are we still in the endless month of June?’ Sabah asks in ‘In The Park For Daily Exercise), although, equally, not essential that we understand them as such. We’ve all spent a lot of time indoors over these last months, flexing our lives around domestic routines that begin to feel like rituals. ASTYNOME perpetuates a sense of claustrophobia and frustration: ‘I’m never as angry with you as when/ I remember you are not dead.’ With a blend of social media realities, contrasted with a longing for physicality, the poems assume an immediate journalism of experience, a record of the moment in all its fury, reminiscent of the mental energy of Fran Lock’s most recent collection, or even a more wronged Frank O’Hara.

Always your silence

and my effusion,

oh fucking speak so I can ignore you.

('In The Park For Daily Exercise')

The two chapbooks of Heredity/ASTYNOME showcase themes of family and love, enacting a reclamation of places and voices. While reading Sabah’s work, I was struck by the essential difference between the ‘poetic’ and poetry. The poetic aspires more than it achieves, and is basically what novelists invoke when they want to be to be taken seriously. Poetry is what Sabah practices: direct and persuasive, where the modes of personal and literary history intersect. Look out for more of her work.