James Peake

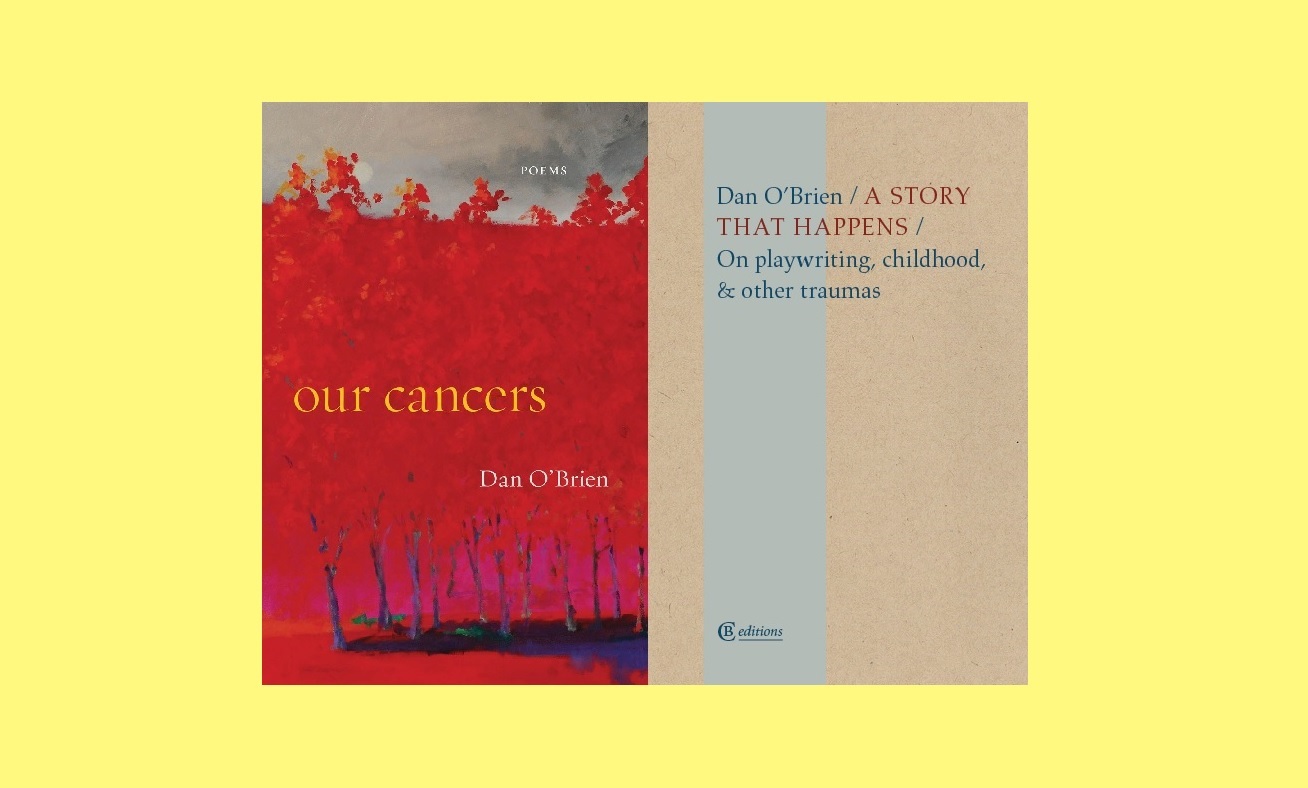

The photojournalist and Pulitzer-prize winner, Paul Watson, is a friend, collaborator and in “complicated ways, almost family” to the poet and playwright Dan O’Brien. He tells O’Brien that “people don’t notice how quickly we die”. You might expect such from someone who has successfully reported on some of the most troubled places in the world. There is no shortage of ways to instantly cease to be. Unless, that is, your death – or your prospective death – decides to be slow. Jessica St Clair, O’Brien’s wife, was diagnosed with Stage 2B breast cancer and underwent surgery and chemotherapy which would ultimately be successful. But “on the day of [her] last infusion” O’Brien had a colonoscopy which revealed Stage 4 cancer of the colon. He would undergo two major surgeries and chemotherapy in the nine months from that point. The list of what he had removed or whittled or shrunk is difficult reading. In the essays and memoir of A Story that Happens (CB Editions, 2021) – behind which title the Robert Lowell of ‘Epilogue’ lurks – and the sometimes overlapping and complementary poems of Our Cancers (Acre Books, 2021), O’Brien brings impressive range as a writer to speak implicitly and explicitly about these personal disasters.

All the time that St Clair and O’Brien were receiving their life-saving treatment they were also learning to be parents. Their daughter was less than two when this terrifying coincidence of disease occurred. Except there’s a chance it wasn’t a coincidence. Years previously St Clair lived in Battery Park and both she and O’Brien were at her flat when it was filled with the dust from 9/11. Whether that dust was the carcinogen responsible or whether it was some other unidentified factor – O’Brien will winningly slam the door on an acupuncturist who blames his “unexpressed anger” – the suspicion creates a fascinating and belated dimension to that atrocity, as well providing an important bridge to O’Brien’s creative collaborations with Watson.

It was Watson who took a picture of the desecrated remains of a US Army Ranger, Staff Sergeant William Cleveland, in Mogadishu in 1993. He recounted hearing a voice, that of the dead soldier, saying that if he took the photograph, “I will own you forever”. It wasn’t like Watson hadn’t photographed the dead before, but something about this was different. Watson would spend many years wrestling with his decision to shoot and this dilemma would result in O’Brien’s Kennedy-Award winning play, The Body of an American, in 2014, as well as a book of poems, War Reporter.

When we speak of disease we often do so in martial terms. Illness can “advance” or be “combatted”, so-and-so is a “fighter”. But as Paul Muldoon will remind us, metaphors are only true to a point. My love is only so much like a red, red rose. O’Brien is to be praised for openly consenting to this. “Nobody enlists for cancer; the vast majority of soldiers are young while most cancer patients are middle aged or older…the cancer patient is not required to commit state-sanctioned murder”. And yet, O’Brien concludes, such metaphors “can be therapeutic, even vivifying. I feel that I have fought in a war, and I have returned with new knowledge.” He is changed forever.

“I worried for a long time”, he continues, “I still worry – that the cancers came as retribution for the transgression of writing about Paul’s transgression of taking his pictures of war.” Watson himself is allegedly prone to the same – what to call them? – inklings or superstitions? “Retribution” is a frightening word and, in as self-aware a writer as O’Brien, carefully deployed. I take it to acknowledge the artistic guilt of writers who know that – unpalatable as it is – political stability and affluence are costive muses whereas their opposites (we might also say absences) will provide material enough for drama of any magnitude or extent or duration. There is too the unignorable political dimension to that word in the context of those attacks. That the dust from the collapsed towers might’ve somehow provoked the cancers in husband and wife sits in uneasy relation to those controversial suggestions that the US “had it coming” (Harold Pinter being a vocal representative of this position at the time). To be clear, I don’t suggest that O’Brien feels anything like the same way as Pinter et al about the attacks but rather that if certain physical acts can have unguessable consequences generations hence then the same must pertain in the mental realms. That certain lives or happenings are assumed unconnected can be a self-protective illusion which the poet or journalist is responsible for dispelling, however briefly.

As a book of poems Our Cancers is made up 101 modest lyrics. They’re reminiscent at times of Americanised vacanas, a form of Bhakti poetry which Ted Hughes turned to in the 1970s when he’d convinced himself that a persistent sore throat was cancer. Hughes’ knowledge of the form derived entirely from A.K. Ramanujan’s translations in Penguin Classics and the appeal for him was that these poems “rounded the circle”, being both “depersonalised and…highly personal at the same time”, a tension or polarity readily applicable to O’Brien’s lyrics. They are a form of prayer.

The 101, then, are small-voiced, attentive and range comfortably across time and space. The most successful of them make deft use of enjambment as a means of synchronising the poem’s divulgence with the reader’s progress. Poem 73 is an exemplar of this, where each line doesn’t end so much as pause for breath: “Dear child/our hope is you/will not need to learn…”. There’s enviable control here and if some verses are low on friction the whole is in service of conveying a genuine modesty about life when you’ve been existentially humbled. There are also beautiful observations throughout: “her hair/floats in/the trash”; “a standing/ovation/of stones”. And one that shocked this reviewer back to a London hospital in the early nineties: “the scar shone/in his neck like/a millipede.” Yes, absolutely it did.

It’s only fitting that 9/11 in its magnitude, cruelty and surreality would engender a long and varied literary legacy. Giants like DeLillo arguably tried to nail it down too quickly. Now that, if such a pun is pardonable, the fateful dust has settled, new perspectives are available. At one end I would place Dan O’Brien’s two books, sober, decorous, honest. At the other I would put Steve Erickson’s Shadow Bahn, in which the Twin Towers rematerialize in Southern Dakota and become an anomalous shrine-cum-memorial to the arbitrary nature of survival (the sole inhabitant of the reappeared towers is Elvis’ stillborn twin). O’Brien’s quieter, humbler works speak just as successfully to our ability to wreak violence against the bodies of others – in the name of medicine as well as baser purposes – but they also suggest a connectedness we can rarely entertain, let alone out-compass. Suppose the dust inbreathed did cause those cancers. Suppose the inability of a dead soldier to consent to publicity was another form of desecration. O’Brien’s books are raised far above the run of subjective accounts of recovery. Not once does he beg for pity or trumpet his family’s remarkable defeat of the odds. You can’t finish these books without wishing them all continued health. But where the books most fully succeed are as uneasy and compelling irruptions of American conscience.