Lily Searstone

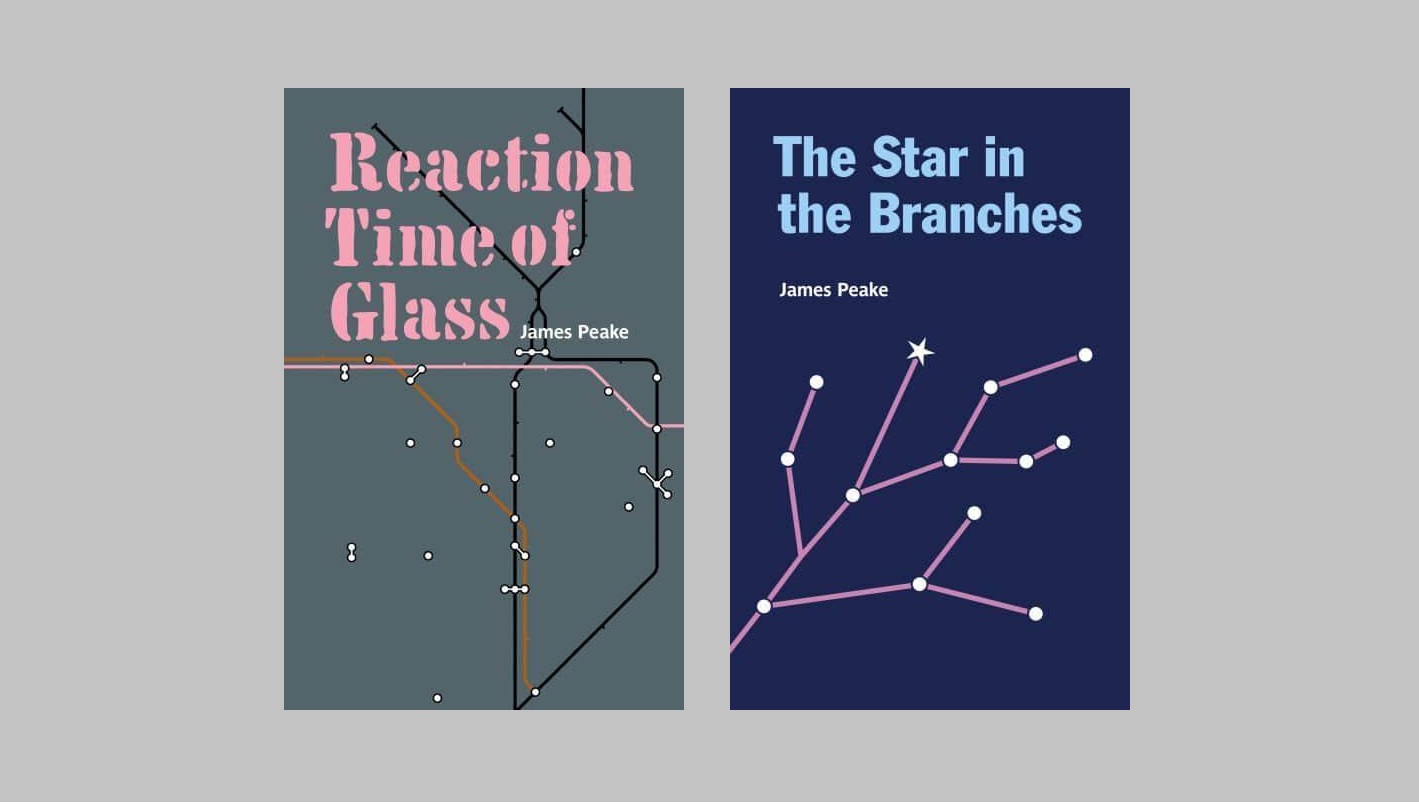

Through fragmented visions and memories, James Peake’s second collection, The Star in the Branches (Two Rivers, 2022), seamlessly distils the past, the starkness of contemporary life, and premonitions of the future, to create an introspective – yet also transportive – portrayal of the fractured times we find ourselves living in.

The opening sequence, ‘The Angel of Unsustainable Complexity’, sets the tone; in an “overwhelmed London”, its “drowned volutes of car parks”, each of us is mere “audited decades of search” who – as the months and years go by – discover have “added nothing to the available real”, “privacy a fallacy and deadlines for all”. Forebodingly, “the children are learning our ways”. These sinister, twenty-first century echoes of Eliot’s “heap of broken images” are mirrored in a more local fragmentation: a loved-one has an MRI scan, the “shadows” and “gaps” of dementia loom.

The temporal nature of Peake’s descriptions contributes to the very visceral experience of reading his poetry. For example, the insertion of principles of the Ionian philosophers adds an interesting foundation of Classical thought to his contemplations of time and space, connecting the past to a constantly-shifting definition of the present. This emphasis on the ancient and immovable is most apparent in the sequence ‘Kouros’. There are intimations of a parallel between these Ancient Greek sculptures – “mute and resisting of time”, outliving the civilisations that created them – with dementia, which can be said to be a resistance to experiencing time linearly. Peake makes sure in the first lines of the poem to reiterate that it is “without choice” that such entities as trees and kouroi lack autonomy; interesting examples of lasting forces of nature that hold some element of life yet are not living as we are. Once again this echoes the very particular state of dementia, where the sufferer – perhaps at times experiencing time elided, non-sequentially – may be said to be living life out of time.

The collaboration of ancient discourses with Peake’s analysis of the mind has a particular retrospective effect on the reader’s experience:

Much worth knowing doesn’t travel, textbooks fall out of date, Anaximenes blows into his hands because air, like language under pressure, changes temperature

This excerpt from the opening poem of ‘Kouros’ draws the significance of language towards the fundamental elements of life, reinforcing the notion of flux, the required evolution of such principles in parallel with a rapidly changing social dialogue. The Ionian philosophers such as Anaximenes centred their theories around the supposition of an ‘arche’, which claimed to be the beginning principle of all things. As Peake draws parallels between the powerful forces of air and language, we are encouraged to recognise the importance of language, and the consequences of its breakdown. This sentiment is further explored in Peake’s delving into the shadows of the mind.

Peake demonstrated his ability to alter spaces, how we see or experience our surroundings, in his similarly urban and fractured first collection, Reaction Time of Glass (Two Rivers, 2019). His commentary on the ‘Middle Places’ of the mind, and the liminal spaces of interaction we typically dismiss, is worth considering alongside the more psychological language we encounter in The Star in the Branches. In ‘The Middle Places’ –

Silence can be fierce or expensive, a place from which opposites confirm us like the polished glass and the metal behind.

Peake goes on to muse: ‘It’s easier to tune in to what you mean / when there’s touch, when there’s no in between.’ The intimacy of these rhyming clauses propounds the significance of the sensory human experience. Peake explores the liminality of existence in such a way that abstracts even the most fundamental of human interaction, but the voidness of the in-between is collapsed by moments of physical connection. Such connections are scattered through Peake’s sobering, stark debut, keeping a spark of hope alive that there is meaning in existence.

The reader is led to equate the chaos and – at times – hostility of the city with that of the decaying mind. The interesting distortions of light, shadow and colour in Reaction Time of Glass help us see the city as new – like the mind, a constantly altering environment, and both affect each other: ‘The dark adjusted us’, he writes in the collection’s opening poem, ‘Storm’. Descriptions of London as ‘rife with schools of shadow’ have crossed over into the mind in The Star in the Branches, which explores the blank spaces of forgetting. This relationship between Peake’s two collections, the trajectory of exploration from the physical into the psychological environment, make reading his poetry all the more enriching. His simultaneously pin-sharp and trance-like poems present reality and existence anew, changing the parameters of our perception. In so doing, they are brilliant mirrors held up to – and artefacts of – this, our postmodern age.