Mark Valentine

On the trestle table beneath the balconies and chandeliers of the Winter Gardens in the old spa town there was a run of pocket-sized poetry journals. The coats that carried a copy when it had just come out would have also contained an identity card and a ration book, probably a crumpled packet of cigarettes and a box of matches, and perhaps a notebook made from rough ‘economy’ paper.

Illuminated by my interest as I riffled the pages, the woman on the stall named a price for the lot, a score or so issues, which I took. That will probably be the only sale I make all day, she said, lugubriousness being an art perfected by second-hand booksellers.

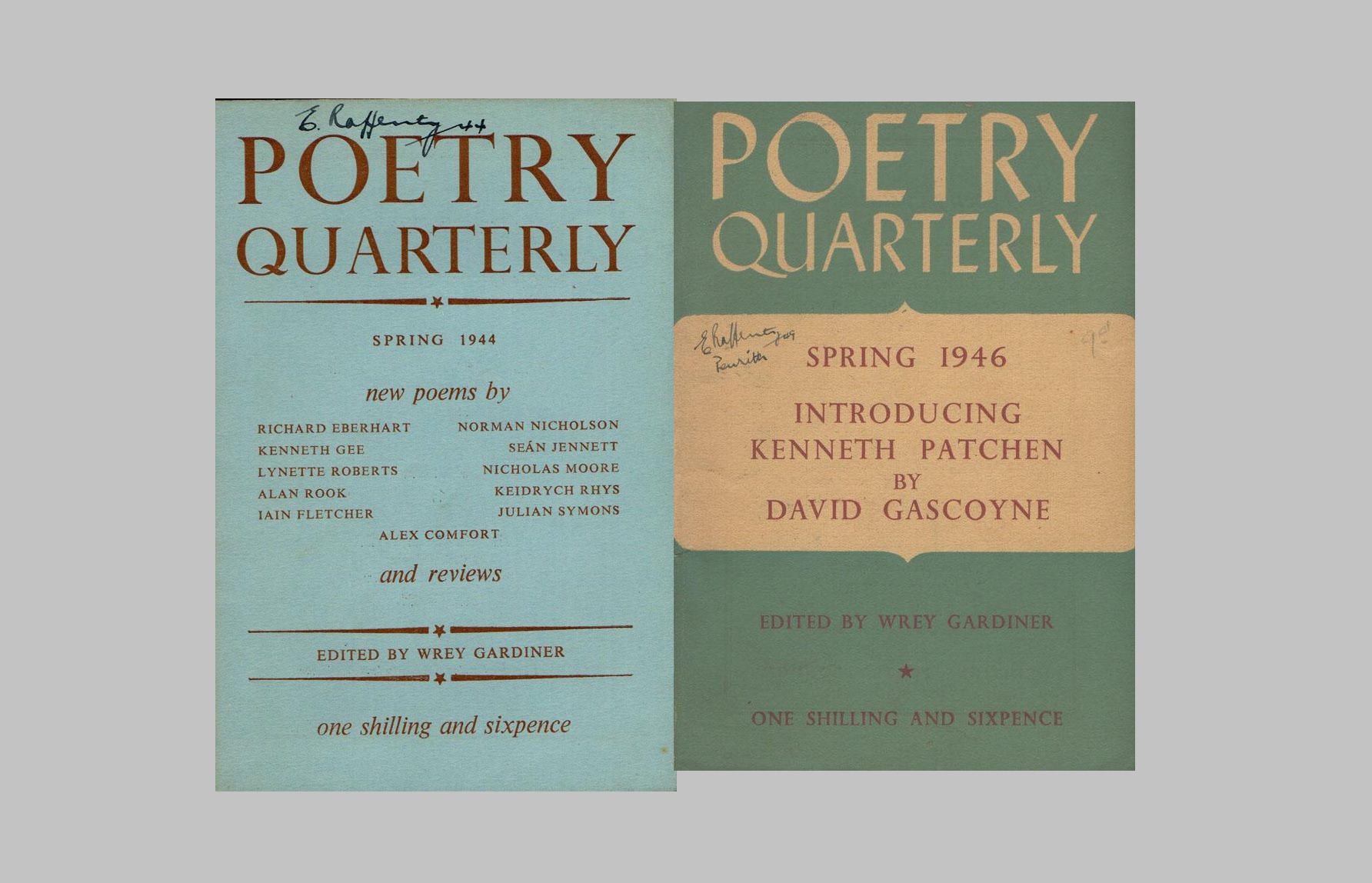

I like looking at old periodicals because they give you a sense of their time, the cross-section of a moment. You seem to catch the tone, the style of that day. These survivals offered that in particular because of the character of their editor. Charles Wrey Gardiner (1901-1981) was a key figure in the poetry world of wartime London, who ran the Grey Walls Press and edited the journal I had just bought in a six inch ziggurat, Poetry Quarterly. He was also a poet himself and the author of several volumes of frank autobiography.

His magazine favoured new young poets, typically in their early twenties, who often drank and smoked and talked together in informal circles around Soho and Bloomsbury. It was loosely aligned to the Apocalyptic and the New Romantic movements of the time, a reaction against the ‘pylon poets’ of the Thirties, but also a rediscovery of the power of symbol and myth.

The atmosphere of uncertainty and camaraderie during the Blitz is well-conveyed in his The Dark Thorn (1946), a year’s journal of his literary life in a run-down cottage in Red Lion Yard, Holborn. At weekends he got away to Grey Walls, his mother’s former antique shop in rural Essex, ‘the haunted house in Billericay High Street’, as he called it, ‘where the ghosts knock and the death beetle ticks, and waits.’ It is an absorbing and strangely cheering read, as he records glimpses of things that interested him (a cat, a clock, a bottle of port, a girl’s mop of dark hair), the flow of his emotions, and the incidentals of his somewhat louche existence. His writing is immediate and authentic. He is also candid about his complicated love life, which involved staying on friendly terms with several previous wives and lovers all at once, though the inspector issuing him a travel permit found it hard to believe he wanted to visit an ex-mother-in-law.

Poetry Quarterly began in 1940 with volume 2 no 1, a sly legerdemain. Owing to paper shortages the regulations did not allow new periodicals to be started, whereas all pre-war ones could be carried on. Gardiner shrewdly judged no-one would ask to see the non-existent or at best theoretical volume 1: not all that many asked for volume 2. But the magazine lasted thirteen years, until volume 15 no 1 in 1953. It published George Orwell (reviews), Muriel Spark (reviews and poetry), Mervyn Peake (poems), translations from Max Jacob and Pierre Reverdy: but also a host of other poets, many now forgotten.

Among those most often mentioned by Gardiner in his memoir is Alex Comfort, then a 20 year old budding poet qualifying as a doctor, but later to win fame and wealth in the Swinging Seventies as the author of The Joy of Sex (1972). Another was Nicholas Moore, also in his early twenties, whose early selection of poems The Glass Tower (1944) was illustrated by Lucian Freud. His prolific work—Gardiner records him typing up a poem a day on average— soon fell into neglect for over fifty years, until a recent revival led by Peter Riley, Iain Sinclair and others.

Another young poet of a similar age who is glimpsed in the journal was Derek Lindsay, later to be the author (as ‘A E Ellis’) of The Rack (1958), a well-regarded autobiographical novel about a young Englishman’s stay in a TB sanatorium in the French Alps (a restored version, adding 25,000 words, was issued in 2016, through the zeal of Alan Wall). Poetry Quarterly also published a tribute by Comfort to Os Marron from Lancashire, whose father was a miner and mother a cotton worker. His poems were well-regarded by Forties editors. Marron died aged 30 from TB.

As well as the poets who flit through the pages of Gardiner’s journal, there were plenty of other interesting voices whose work he selected. They included Eithne Wilkins, whose work in Poetry Quarterly is particularly otherworldly. She was a translator from German, and an authority on Robert Musil. Married to Ernest Kaiser, with whom she co-translated many works, her poetry was also included in Roger Roughton’s journal Contemporary Poetry and Prose and Kenneth Rexroth’s The New British Poets anthology. A now scarce book by her, The Rose-Garden Game, is a discussion of medieval rosaries. I had it but have lost it, possibly in the house itself, possibly not. It’s like the work of Dr Frances Yates, the scholarly, sympathetic study of a symbol. We could do with more of those.

A lot of the poems in PQ seem to be drawn to the uncanny and macabre, perhaps not surprisingly given the times, although this may also reflect Gardiner’s taste. Or possibly I just noticed this more because I write ghost stories, but I don’t think so. There are haunted gardens, shadows in back-streets, moonlit country, the apocalyptic poems of Hugo Manning, who worked by night as a fact-checker for Reuters and wrote by day his poems of ruined cities and mythical figures. Robert Graves’ The White Goddess, just out in Summer 1948, is favourably noticed: ‘It is impossible to do justice to so important a book . . . the poet should turn to Mr Graves for consolation and encouragement.’

A young poet who was later to achieve some wider recognition was John Heath-Stubbs, who contributes a poem, ‘Churchyard of St Mary Magdalene, Old Milton’ about a prodigal son revisiting the village where his father was parson. It begins as a ‘meditation among the tombs’ but opens out at the end into a trust in the resurrection, linking this to myths of the wounded god, derived no doubt from Frazer’s The Golden Bough: a persuasive shift into old magic. His first booklet, Wounded Thammuz (1942), shares this theme.

Haunted terrain is also seen in Sydney Tremayne’s poem on Ballaculish, a wild, ‘tameless’ land: ‘here man is marginal’. He was a Daily Mirror journalist and an auxiliary fireman whose verse work seems the opposite of these busy occupations: reflective, attentive, often about solitary walks and lonely ruins. The Scottish Poetry Library website has some pages about him.

The eerie poems in the magazine also include an uncanny, rather Sitwellian one by a Charles Fox (could this be the future Radio 3 jazz presenter?), ‘Ballet Matineé at Bournemouth’, in which he sees both the performers and the audience as crystal figures with colours swirling inside them. And in the Autumn 1950 issue, there is a particular favourite of mine, ‘Now in the Prevalence of Favourable Omens’, a doomy moody poem in the mode of Walter de la Mare, though in avant-garde lower case, by the otherwise unknown Peter Stanford. It is about a spectral visitor to a ruined manor: ‘why do you always come at night/in this old walled garden treading carefully/between the heaps of thistle-decked rubble/and lifting your dated dress/in case you soil the much-mended hem’. There is no book by an author of that name from that period (there is a much later namesake), nor I have seen any contributions to other periodicals. The poet is as ghostly as his poem.

I was also struck by Denise Levertoff’s ‘Poem’ of Summer 1946 about diffident, gentle wanderers, people who ‘are happier/with ghosts than living guests in a warm house’: ‘They drift about the darkening city squares/coats blown in evening winds and fingers feeling/the worn edge of a book, or finding/familiar holes in pockets . . .’ Gardiner refers to her as one of those sympathetic to his vision, a companion of the Red Lion, both in his Holborn cottage and the pub of that name in Billericay, but she moved to the USA the following year and made her poetic career there.

I noted at the back of one issue a mostly complimentary review of a book by Ian Critchett, The Spider’s Web, which had arrived at their offices with no details of publisher, printer or date. The reviewer thought it very promising. It turns out this was by the baronet Ian George Lorraine Critchett and it was published at Krefeld by Scherpe-Verlag, 1946, along with another booklet, Hunting Spider. The Times obituary for Critchett begins, ‘Vetting and personnel officer at MI6 who was also a lifelong poet. An intelligent, delightful and many-sided man. . . .’

We could do with the services of the intelligence agencies in tracing some of the lost poets glimpsed in these journals. There are four poems from a sequence called ‘The Silver Circus’ by John Dillon Husband, an American poet, about a broken carousel, the tightrope walker as poised as his cigarette, the fortune-teller Lily and her smoky globe: a cavalcade of bright strange images like tarot cards. It was originally published in the New Mexico Quarterly. There is no book by him in the catalogues either, and very little else shows up, except a couple of other contributions to journals. What became of him?

Among many, the poet whose work I would most like to see revived is Gloria Komai, who wrote in an Imagist style in clipped enigmatic lines but with an indefinable inner lustre. ‘Brevity lingers: a scent’ she said in one paradoxical line, noticing that it is fleetingness we often most remember and cherish. She worked for The Sylvan Press, who specialised in well-designed and illustrated books on the arts and practical guides to handcrafts.

Nothing much seems to be known about her either, but there is a recollection by Derek Stanford in his memoir Inside the Forties (1977), who describes her (misremembered or misprinted as ‘Kemai’) as ‘a gentle and delightful creature, god-daughter of H G Wells’ and the daughter of ‘a Japanese poet and scholar who had committed suicide’ and ‘a charming and lovely Englishwoman’. He thought her work more influenced by European models (Rilke, Mallarmé) than was common in her British contemporaries, but feared her concision of imagery might deter readers. She issued three slim collections in the Forties, then no more. Thirty years later Stanford was unable to trace her or her publisher. He reprinted one of her poems anyway.

There are other discoveries to be made in these journals. There is for example, a reaching-out to other European poets, mostly French, but including choices from Spain, Italy, Greece, Germany, the sort of awakening interest that would lead to the Penguin Modern European Poets series in the Sixties. There are some of the early poems of W S Graham, already notable for their tumbling, incantatory diction, and an essay about him, and a similar early championing of the English Surrealist poems of David Gascoyne.

Though he is not much mentioned in its pages, the circle around Poetry Quarterly seem to me the heirs of Yeats, with the Irish mage’s keen interest in mysticism and the occult, in spiritualism and automatic writing, in ghosts and fairies. They gave way to the exact opposite: the kitchen-sink realism of the Fifties, the classical restraint of the Movement, and they have for a long time been lost behind that bulwark. But the uncanny and the dream-like and the strange are as much a part of human experience as the neat and the solid and the everyday, maybe more so. There is much worth rediscovery, about them and about ourselves, in the work of the poets of the Haunted Forties.

Mark writes for Wild Court on some avant-garde poetry of the 1920s here and some student poems of 1965 here.

Comments

One response to “The Haunted Forties: Wrey Gardiner and Poetry Quarterly”

[…] Read the complete article […]