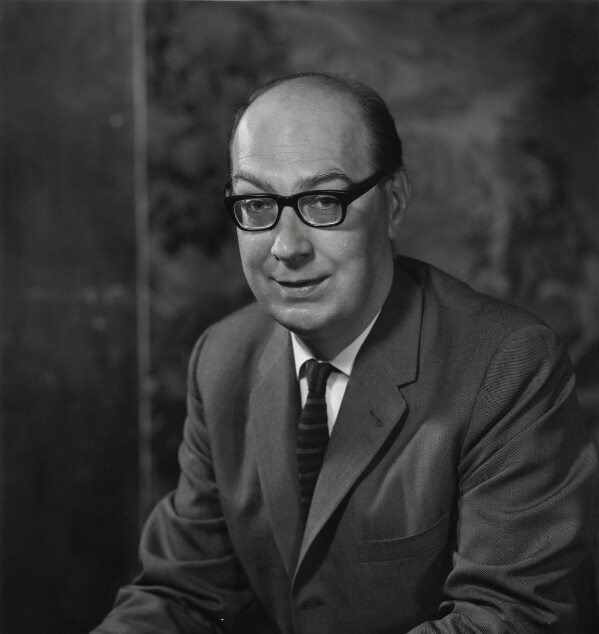

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Nicola Healey

In Sinéad Morrissey’s collection On Balance (2017), Morrissey selectively quotes from Larkin’s ‘Born Yesterday’ (1954) as the epigraph to her titular poem, ‘On Balance’.[1] She decontextualises his lines, however, to bolster her poem’s feminist drive, distorting Larkin’s poem and misleading the reader from the outset. In a review of Morrissey’s collection, Ellen Cranitch writes that ‘On Balance’ takes on ‘some particularly misogynistic thoughts of Philip Larkin’, a comment that automatically replicates Morrissey’s misrepresentation.[2] I want to revisit Larkin’s whole poem, together with Morrissey’s poem and its reception, to demonstrate the ways in which Larkin and his poem have been misused, and how the trend towards merging received preconceptions of his life and character with his work continues to gain widespread traction, undermining his literary (and personal) reputation.

‘Born Yesterday’ is written ‘for Sally Amis’, daughter of Kingsley Amis, and is an act of care on the occasion of her birth, albeit one containing unconventional, refreshing wisdom. ‘May you be ordinary’, Larkin writes, have

Nothing uncustomary To pull you off your balance, That, unworkable itself, Stops all the rest from working.[3]

Those who are ‘out of the ordinary’, Larkin suggests (with hovering self-awareness, and thus self-depreciation), can struggle practically in life, to the point of dysfunction and stasis – something that the lives of artists and thinkers throughout history have shown. In reality, having ‘uncustomary’ aptitude tends not to lead to increased wellbeing or equilibrium, but a greater propensity for pain, anxiety, over-thinking and depression. Larkin himself tells us this, four years prior to ‘Born Yesterday’: when he was 27, he wrote to his friend James Sutton that ‘Imagination & sensitivity are also great bringers of distress & are capacities for which no adequate function seems to have been provided.’[4]

Morrissey’s epigraph ends on the words ‘In fact, may you be dull’, which does sound callous when left hanging like that: the blunt word ‘dull’ becomes unduly amplified and collects in the ear like cloth. Larkin’s poem unfolds and concludes, however, with the exuberant conditional lines

[…] – If that is what a skilled, Vigilant, flexible, Unemphasised, enthralled Catching of happiness is called.

Larkin exalts the so-called ‘dull’ and ‘ordinary’ (ll. 20, 12) – and these words, which Morrissey presents literally, are charged with knowing irony and wit in their original context (he means their opposites), an integral linguistic layer which Morrissey disintegrates, as though paint stripper has been taken to his voice. Larkin is satirising those who wish the world for each new life – ‘They will all wish you that’ (l. 8) – when this cannot possibly be realised for every individual. Moreover, he suggests that being ‘dull’ may be a surer, more sustainable route to ‘catching’ ‘happiness’ in the real world, if to be ‘dull’ is to be capable, vigilant, flexible, balanced, in the background, fascinated. Interestingly, in 1955, a year after ‘Born Yesterday’ was written, Larkin (then aged 32) wrote to Monica Jones that he felt ‘not only not happy but not competent, not skilled, practised, adroit’ – the same attributes in life adeptness that he outlines in this poem, and evidently admired.[5] (It sounds as if Larkin is being characteristically too self-critical here, as he was a highly competent, skilled and accomplished librarian, and he excelled in this field of work.)

Paradoxically, Larkin saw ordinary living as being remarkable and worthy of attention. Perhaps he realised that he had to, to make life liveable and fathomable, just as many now find that the principles of mindfulness – paying close attention to everyday things and acting with intention – can enlighten the mundane and the routine, leading to an enhanced state of wonder, balance and buoyed mood, ‘catching’ the participant in a net of ‘happiness’, for want of a better word. Larkin himself embodies this paradox of the extraordinary–ordinary as he was both exceptionally gifted and, arguably, arrested by humdrumness. As he once defiantly asserted, ‘I don’t want to transcend the commonplace, I love the commonplace, I lead a very commonplace life. Everyday things are lovely to me.’[6] So, he defends and valorises a form of humanist immanence. I am not saying that Larkin’s grounded, democratic vision is right – the grass is always greener, one might say to him – but it’s a bold and compelling insight. Even Larkin, with his conditional ‘should’ (l. 9) and ‘ifs’ (ll. 11, 21) – essential hinges in this well-balanced poem – does not force this unusual birth-day benediction on to Sally Amis and the reader as an absolute; he merely, with measured foresight, carefully imparts his experiential wisdom.

Dull is the perfect, mimetic word choice for Larkin to probe and subvert here. Aurally, it sounds heavy, like the toll of a bell. Its monosyllable, dying on the double ‘l’, makes it appear and sound self-limiting, as though being prevented from ‘ringing out’, like a muffled bell. As well as the obvious meaning – boring – dull means to not shine, or to lack sharpness or sensitivity. Larkin brings out the finer edges and the lustre in ‘dullness’. Morrissey’s poem ends by using the words ‘brilliant’, ‘radiant’ and ‘incandescent’ to describe her daughter, who is ‘so far’ ‘from dull’ (ll. 21, 23). I’m sure many parents would say the same about their children, and this fierce maternal wonder and pride is to be admired. But in a poem, understatement and layered ambiguity is often more powerful and enduring, and more inclusive of the reader. Larkin tended to find and to reveal the transcendent in unusual, subversive ways, such as through everyday life – ‘where we live’, as he reminds us in his poem ‘Days’. We are all bound by the balance and monotonous strictures of days; ‘balance’ in the sense of managing both each day and the ‘long haul’ of time (being the tortoise, not the hare), and reckoning with what remains, of time and life.

Larkin’s word ‘catching’ is also interesting. It brings to mind catching fish in a net, and the sustenance this delivers (given that happiness is a slippery concept, I like the idea that ‘happiness’ here might replace a haul of fish). It also evokes continually ‘catching’ the ball of ‘happiness’ in the game of life: luck and serendipity, being in the right place at the right time, though he is ultimately invoking a more diffuse experience than this. Continual aliveness is his main concern, a process of being and living, not just highpoints in life. As he wrote to Robert Conquest with an alteration to this poem’s manuscript, when Conquest wanted to include ‘Born Yesterday’ in the anthology New Lines, the word ‘Catching’ is essential to his meaning: ‘I want to suggest something continuous through life, not just one isolated instance [of happiness]’.[7]

More negatively, ‘catching’ has an undertone of being easily infected by a contagion. Even when encouraging a modest happiness, Larkin cannot quite detach this state from being deceived or corrupted, as though to be unhappy would be a truer, more honest condition, and whereby happiness, or contentment, is almost an illness that he wants to ward off, or at least structure in proportion to reality and make ‘workable’.

Larkin’s inability to settle down and marry, needing instead to hold on to his ‘glittering loneliness’, as he wrote to James Sutton, supports this idea of keeping what society holds to bring happiness at arm’s length, lest it interfere, in his case, with what he felt to be his primary work and purpose on earth: poetry-making.[8] To ‘give in’ completely to another person, Larkin feared, would cause a ‘slackening and dulling of [his] peculiar artistic fibres’, and ‘spells death to perception and the desire to express, as well as the ability.’[9] Larkin wanted his poems to shine, even if that meant making sacrifices in his personal life. When I first read Larkin’s dazzling image of immersion within ‘glittering loneliness’, I recalled Septimus in Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway: ‘now that he was quite alone, condemned, deserted, as those who are about to die are alone, there was a luxury in it, an isolation full of sublimity; a freedom which the attached can never know.’ Larkin might have wanted to catch happiness, but he didn’t want to be caught by it, and become a dulled, dead fish, a fly trapped in a web of attachment and domesticity. He wanted to have his cake and eat it. As he wrote to Monica though, ‘most people not only want but must have their cake and eat it as well.’[10] If we’re honest, many people are similarly conflicted. Larkin was just remarkably aware of, and honest and clear about, his self-conflict.

To my mind, Larkin’s poem is not fuelled by misogyny but simply by both lived knowledge that gifts are often mixed blessings that can dominate, even blight a life, knocking it out of kilter; and by his extra-ordinarily clear-sighted view of the nature of life and its limits. He combines this practical wisdom with avuncular vigilance over the future welfare of an author-friend’s child, delivered with characteristic realism, honesty and subversive allegiance to truth. The pivotal issue in Larkin’s poem – as there can be existential concerns which are as important as feminism, but which are less defined and harder to articulate, and so lack the force, status and attraction of an easily-classifiable and recognisable group identity – is not gender, but long-term human adjustment, wellbeing and stability: life balance. He makes a radical case for the overlooked virtues of steadiness and plodding on, in both ambition and feeling (as what goes up must come down). In a sense, he wants to wrap Sally Amis in cotton wool – ‘dull’ her from potential suffering, however impossible that might be. When he says may you ‘Have, like other women, / An average of talents’ (ll. 13–14) – I admit, not exactly inspiring words – he means may you fit in, which is usually what parents most want for their child.

Larkin’s wish for Sally Amis to have ‘An average of talents’ also has strong echoes of Thomas Hardy’s ‘A King’s Soliloquy’, which envies the common passage through life of ordinary men: ‘I think, could I step back / To life again, / I should prefer the average track / Of average men’.[11] As Hardy was a great influence on Larkin, it seems likely that he was directly invoking his poem here and that the word ‘average’ is not a gender-specific insult, but a desire to feel that one belongs to the general human race and can practically live: the word ‘average’ is being used in the sense of normal and typical, rather than mediocre or inferior.

*

Hartley Coleridge, S. T. Coleridge’s prodigy son, had similarly learned a century earlier how gifts can become burdens: ‘I think distinguish’d intellect no more to be desired than distinguish’d beauty. They who possess either should be thankful and beware’.[12] Hartley was commenting on his nephew, Derwent Moultrie Coleridge, who his parents were worried about for being ‘not as gifted as a Coleridge ought to be’.[13] Hartley Coleridge, like Larkin, defended the merits of ‘ordinariness’, regardless of gender, knowing that being ‘distinguish’d’ can lead to disappointment. By definition, to be distinguished is, in some literal sense, to lose balance (because one area of life becomes highly elevated and emphasised). Many celebrated individuals, history continually shows us, suffer with this imbalance, or lose perspective in day-to-day, grounded life. To be marked out for only great things, especially as a child in the shadow of a literary father – as Hartley Coleridge was, and which Larkin was trying to protect Sally Amis from being – is to carry a burden of ‘emphasis’, to paraphrase Larkin’s term ‘unemphasised’: a pressure of expectation and responsibility that cannot always be fulfilled or sustained in the real, unforgiving and tarnishing world. Larkin’s poem could be compared favourably to William Wordsworth’s more idealistic ‘To H[artley]. C[oleridge]., Six Years Old’, similarly written for the child of a literary friend (S. T. Coleridge), expressing fears for his future. With unfortunate prescience, Larkin (like Wordsworth) was right to be wary when we consider that Sally Amis died in midlife after suffering for years with depression and heavy drinking – much like Hartley Coleridge.

By wanting the best for Sally Amis, and seeing ‘the best’ as not necessarily springing from the conventional ideals of beauty, love or high achievement – ‘the usual stuff’ that ‘the others’ wish for us (ll. 4, 3) – Larkin’s poem, far from being misogynistic, actually takes on a feminist slant of its own. The truest, or most balanced, feminism would accept and reflect the reality that not all women – or men, for that matter – will shine continually in a conventional sense, or indeed ever, for a multitude of reasons, but that doesn’t mean the ‘average’ life becomes invalid, or any less precious. This is not encouraging mediocrity or stasis; rather, un-blinkered inclusion of the varied topography of existence – which exists, and will go on existing, whether we like it or not. Larkin’s focus is on how the trajectory of a life more often is, not how we would like it to be, and in that sense he does not betray the reader or the perennial present, and the poem becomes strangely hopeful. In his carefully constructed and nuanced poem, he offers the reader a less-deceived safety net: ‘should it prove possible’ to live off a wellspring of ‘being beautiful’, ‘innocence and love’, or ‘uncustomary’ talent (ll. 9, 5, 7, 16) – what received wisdom holds will bring ‘happiness’ – great. ‘But if it shouldn’t’ ‘prove possible’ (my italics), here is what you can live off, and for, as material life won’t stop just because these extra-ordinary, ‘lucky’ incidents fade with, or become complicated by, time (ll. 11, 9). He doesn’t want to set Sally Amis up for a hubristic fall. Or multiple falls, which conventional hopes often do. Larkin, to continue the pun of his poem’s clever title, wasn’t born yesterday, and he’s not going to hoodwink or insult the reader by airing hopes that don’t consider or sustain the whole of a life.

For Morrissey to overlook all of Larkin’s sophisticated empathy, his wide perspective and subtle ambiguities, and cast him with certainty as only ‘the mean fairy / at the christening’, an allusion to Sleeping Beauty, fixes him as a one-dimensional ‘baddy’, reducing him and his poem to a caricature (ll. 12, 13). As Sean Robinson has pointed out in The Scores, Morrissey creates a ‘straw man’ to provide an easier target for her to attack.[14] Given Sally Amis’s end in real life, it is inappropriate to imply that Larkin cursed her at birth – life is not a fairytale. It comes across as an emasculating ad hominem onslaught. I am not sure that the best way of avenging perceived misogyny is with what risks being read as misandry – if not now, then fifty years from now, given how quickly times change, and language use with them. It is also unfortunate and surprising that Morrissey does not name Sally Amis, not even in a note to her poem. Sally Amis becomes just an anonymised, generalised ‘she’ and ‘her’ – hastily appropriated for a cause, rather than a real person.

Truth and accuracy are critical imperatives – it doesn’t help the cause of feminism if we don’t remain faithful to these tenets. Framing a doctored poem with what we think we know about a poet’s private ‘thoughts’– deliberately misconstruing and re-moulding a writer’s words – is surely unethical and continues the trend towards character assassination which has pursued Larkin since the publication of his selected letters in the 1990s, despite the fact that those who knew him have rebutted the socially-conditioned claims made against him. Breaching a poem’s integrity in this way is the poetic equivalent of photoshopping and disinformation; and for a poet such as Larkin who is known to have painstakingly laboured over the construction of his verse, this seems a particularly cruel punishment. Morrissey’s poem incites the easy acceptance and proliferation of derogatory labels, untrue assumptions, and what has become a shorthand dismissal of Larkin. This is unhelpful and concerning, especially when the labelled writer is dead, with no right of reply.

For example, Kate Kellaway writes in The Guardian: ‘And then there is the splendid title poem, taking on Philip Larkin, in which Morrissey arraigns him for his sexism in “Born Yesterday”’; ‘The stinging spirit of this is wonderful.’[15] This view trusts Morrissey’s poem implicitly and wholly overlooks the meaningful intricacy of Larkin’s original poem. Rachel Chanter writes in The Compass that Morrissey’s collection occasionally addresses ‘the wrongs of history, as in the wonderfully bitter title poem, “On Balance”, which takes Larkin to task for his poem “Born Yesterday”’.[16] Chanter admires that Morrissey ‘scoffs’ at Larkin. In The Manchester Review, meanwhile, Sahar Abbas declares: ‘To be brief, I loved it [Morrissey’s poem]. In fact, I think I loved it a little too much. This poem spoke volumes about female empowerment’.[17] I am not empowered by this poem. I feel deceived and dismayed for Larkin; first for the wilful misreading of his poem, second for the needless shredding of his character, as though it is as unimportant and replaceable as a piece of paper. Morrissey has shown elsewhere that she admires Larkin as a poet, but it is surely misguided not to realise that her mishandling of this poem will have consequences for his poetic legacy and reputation. And as Abbas writes, Morrissey’s ‘clear and concise diction only further serves to empower young girls whom look to her, to get educated about the importance of young women expressing themselves as honestly as they can’, which highlights both the sometimes misleading power of articulacy and the significant position of moral influence and responsibility to truth that poetry holds.[18]

Also: indiscriminate empowerment is not a virtue in itself if it springs from a falsity or enacts unjust damage. I’d rather not acquire power through humiliating a dead man. Moreover, not everything is defined by binary gender politics, though these are easier, more vivid, than facing what they mask: the true ill-defined state of life, in all its amorphous and matted complexity, limitations, uncertainty and flux. With the exception of Sean Robinson’s commendable review, the lack of careful consideration of the wider context of ‘Born Yesterday’ is baffling. There is a notable critical silence in defending Larkin’s poem, a vacuum which then allows the chorus of condemnation to take over. It is this ideological myopia which commits ‘wrongs of history’ (when the present becomes the past) by jumping on the tired bandwagon of Larkin-bashing and overwriting his poetry; and also by weakening feminism’s credibility through prime literary and media platforms with critique that is not robust.

I resorted to scouring Twitter. Surprisingly this yielded fairer analysis (I am wary of social media). The poet Mark Granier: ‘Whole point of L[arkin’s] poem = final lines’. The writer Wendy Erskine concurs: ‘Yeah! Drop those lines and he sounds like a dick. Keep them and it’s something else entirely’, to which Granier responds, ‘Yes, and quoting ONLY those other lines seems unfair & inaccurate to me. Larkin could be a dick alright, but rarely in his poetry’ – tersely reminding us of the crucial – some would say sacrosanct – dividing line between a poet’s private life and their poetic artefacts. As Maurice Riordan has stressed with regard to Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath, ‘the imperative of keeping the life and the work on different burners is acute. The personal tragedies cannot be kept from out minds. […] But that mustn’t distort our view of the poems’.[19]

Defacing poems is analogous to removing or even destroying art because the artist – not the artwork itself – offends, a movement which over the last few years has approached puritanical censorship worldwide. Svetlana Mintcheva, director of programs at the National Coalition Against Censorship, has written sensitively and astutely on the double standards and complex risks to artistic and critical freedom – and, therefore, to all our freedom – that this militancy brings, reminding us that ‘Caravaggio killed a man. Should we therefore censor his art?’[20] While this is an extreme example, the genesis of art is often mutually exclusive with convention and social mores, springing, as it often does, from human unrest and conflict. That’s not at all to condone immorality, but a reminder that art transcends society’s order and cannot be traduced if it is deemed that the artist has ‘sinned’ elsewhere. Really, it is us, not the artist, who then lose out, so it seems almost a form of collective self-harm, cultural and historical vandalism and future impoverishment. As a society, we cannot have our cake and eat it: we cannot have great art, and expect the artist to be a sanitised and perfect person.

*

As for whether Larkin showed prejudice against women elsewhere, he does say some anti-women and unpleasant things in his letters, especially in his early twenties, which can make a modern-day reader wince. It would be fairer to consider these in context: of his age, his psychological state at the time, his 1940s–50s’ era, and the human nuances of their private forum (where, for example, Kingsley Amis often provokes in Larkin a performative machismo). After initial feelings of unease, I am not offended. There is a critical tendency to read any fleeting epistolary emission as the ‘real’ person, the essence of their character, and then mould this to fit abstract notions and ideological conceits: fix the person and their mind in time as though they are specimens in formaldehyde (if the nature of human life is flux, why do we act as though death negates this protean state of being?). The fact is Larkin was often extremely anti-himself. His occasional criticisms of women should be seen through this same prism of confusion and antipathy with which he viewed existence itself – which, it seems, many people either pretend they know all about, or don’t probe at all. As Larkin remarked to James Sutton, ‘Most people, I’m convinced, don’t think about life at all.’[21] When Larkin is in a ‘funk’, as he sometimes puts it, the colour of everything changes, just as a depressed person sees the whole world through a different lens.

Indeed, Larkin’s letters reveal that he suffered deep anguish and suffering throughout his life, something for which he is rarely given sympathy and compassion (if we are so keen to re-address historical misogyny and sexism, and, apparently, now so aware of mental suffering, why are we slower to extend that illumination and fairness towards the individual psychological health and disposition of past writers, of both genders?).

Larkin is also sometimes too honest – an admirable quality, but it leaves the speaker exposed. When he was in hospital in 1961, he wrote to Maeve Brennan: ‘I am incapable of dissimulation’.[22] He seemed constitutionally compelled to express certain aspects of life when he saw them clearly (including his own faults), as if truth itself was a religion, an inviolate realm in which he could have faith and which gave life meaning; a form of austere purity, almost worldly asceticism, duty to the human condition, and integrity. His clear-sighted, heightened perception of how things really are, with no mediating, and shielding, veil, can come across as arrogance and insensitivity – and can offend those who are guided more by the black and white, good or bad spotlights of political correctness than by the glimmering fog of uncomfortable reality.

As for age, I wouldn’t want anything I wrote in a private letter when I was 21 to be held against me forever. Yet this is what we do with writers, rather than accept that they were real people with varying and complex moods, stumbling, uncertain lives and developing characters.

It is also worth foregrounding that Larkin rarely enthusiastically and persistently supported any writer, as he had such high standards as to what constitutes literature, but the one writer he did unswervingly invest in and champion was a woman: Barbara Pym. This was to career-reviving effect when, along with Lord David Cecil, he lauded her in the TLS in 1977 as the most ‘underrated’ novelist of the twentieth century, ending her 15 years in the literary wilderness, after publishers had, with brutal short-sightedness, no longer deemed her style in keeping with the times.[23] Larkin certainly didn’t find Pym ‘average’ in the derogatory sense, but remarkably talented and unjustly abandoned. He wrote to Monica that he found Pym’s work ‘depends on such tiny lowly things’ – ‘dull’ things, you might say, the quotidian fabric of our lives – and as such her novels were ‘absolutely pulsing with life’.[24] Pym’s bravery, dignity and perseverance in the face of senseless rejection are breathtaking. If it wasn’t for Larkin, it is unlikely that she would have enjoyed the renewed acclaim that she received before she died of cancer just three years later. It is impossible to measure or put into words his service to Pym, both diffuse and direct, of selfless goodness. This, along with his poems, is where the measure of his character rests.

Larkin was kind, widely affectionate and polite, valued and loved by those who knew him, including many women, who he valued and loved in return, as Ann Thwaite, who knew Larkin well, reminds us in a recent letter to the TLS (on 16 March 2018), in response to ‘J. C.’s casual inclusion of Philip Larkin, in the context of sexual harassment’ the previous week: ‘Philip Larkin loved women, as many women have attested.’[25] Thwaite quotes from Kingsley Amis’s poem, ‘A Bookshop Idyll’, when she continues: ‘Like one of his friends, Larkin thought “Women are really much nicer than men. No wonder we like them”’.

For lucidly rendering both the banalities and the gleam of life as it is lived, not how we would wish it to be, thereby sustaining generations of real (as opposed to theoretical) people, Larkin is cherished by his readers, regardless of his private life. Writing to Monica in 1951 on his admiration for Dorothy Wordsworth’s journals – Larkin had felt ‘shamed by the observation and quickness of [Dorothy Wordsworth’s] spirit’ – Larkin said: ‘If I have any wish in life it would be to “express” or “render” life as I have known it, but it is such an enormous task I admire more & more people who achieve the smallest success in that line.’[26] But achieve great success in ‘real-time’ memorialising of self-in-environment is precisely what Larkin did. He also had the humility, and foresight, to defer to the lesser-known (especially in the 1950s) female Wordsworth. His recently published Letters Home, furthermore, reveal a man with an extraordinary and steadfast sense of filial duty to his mother, Eva.[27]

*

Morrissey’s On Balance received wide attention and notable prizes, success which, along with its titular poem, risks mythologising Larkin, solidifying him as a scoundrel in public consciousness and discourse, to be pilloried rather than read, deforming his reputation for a new, more reactive generation and for posterity. Thankfully, the plain excellence of Larkin’s poems is such that they will not be forgotten. Then again, this is what nineteenth-century reviewers said about Hartley Coleridge. It would be a travesty if Larkin were ever to become a ‘sad example of the poet’s lot, / His faults remember’d and his verse forgot’, as Hartley Coleridge knew was often the poet’s fate.[28] Very few lives would emerge from magnified scrutiny looking faultless. It is a failure of cultural guardianship if we twist or overlook what are some of the finest, most giving and moving poems of the twentieth century because a current of self-righteousness overpowers the harder human potential to be magnanimous and self-aware. In the balance, a poem should survive or fall on its own terms, and ‘Born Yesterday’ survives.

It matters that distortions, of both text and author, are countered and challenged, before the silencing blanket of time takes over, whereupon a writer can be reduced to a cipher, overlaid with whatever a shifting society projects on to them, rather than what they were, dulling the original, diamond-cut voice. Larkin the man is not beyond reproach, but for the hard-won gifts he bequeathed to us, Larkin the poet deserves more than this.

[1] Sinéad Morrissey, On Balance (Carcanet, 2017), p. 11.

[2] Ellen Cranitch, The Poetry Review Vol. 107, No. 4 (Winter 2017): 109.

[3] Philip Larkin, Collected Poems, ed. Anthony Thwaite (The Marvell Press/Faber & Faber, 2003), p. 54.

[4] Selected Letters of Philip Larkin, 1940–1985, ed. Anthony Thwaite (Faber and Faber, 1993), p. 156.

[5] Philip Larkin: Letters to Monica, ed. Anthony Thwaite (Faber & Faber/Bodleian Library, 2010), p. 160.

[6] ‘An Interview with John Haffenden’, in Philip Larkin, Further Requirements: Interviews, Broadcasts, Statements and Book Reviews 1952–1985, ed. Anthony Thwaite (London: Faber & Faber, 2002), p. 57.

[7] Selected Letters, p. 250.

[8] Selected Letters, p. 116.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Letters to Monica, p. 199.

[11] Thomas Hardy: The Complete Poems, ed. James Gibson (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2001), p. 374, ll. 33–6.

[12] Letters of Hartley Coleridge, ed. Grace Evelyn Griggs and Earl Leslie Griggs (London: Oxford University Press, 1936), p. 268.

[13] Raymonde and Godfrey Hainton, The Unknown Coleridge: The Life and Times of Derwent Coleridge, 1800–1883 (London: Janus Publishing Company, 1996), p. 231.

[14] Sean Robinson, The Scores (Winter 2017): http://thescores.org.uk/on-balance-by-sinead-morrissey/.

[15] Kate Kellaway, The Guardian (24 October 2017): https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/oct/24/on-balance-sinead-morrissey-poetry-review.

[16] Rachel Chanter, The Compass: https://www.thecompassmagazine.co.uk/rcr1/.

[17] Sahar Abbas, The Manchester Review (October 2017): http://www.themanchesterreview.co.uk/?p=8492.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Maurice Riordan, Editorial, The Poetry Review Vol. 105, No. 4 (Winter 2015): 6.

[20] Svetlana Mintcheva, The Guardian (3 February 2018): https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/feb/03/caravaggio-killed-a-man-censor-art.

[21] Selected Letters, p. 156.

[22] Selected Letters, p. 327.

[23] ‘Reputations revisited’, TLS (21 January 1977): 66–7.

[24] Letters to Monica, p. 371.

[25] Ann Thwaite, letter to the TLS (16 March 2018): https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/letters-to-the-editor-169/.

[26] Letters to Monica, p. 74.

[27] Philip Larkin: Letters Home, ed. James Booth (Faber & Faber, 2018).

[28] ‘Young and his Contemporaries’, in The Complete Poetical Works of Hartley Coleridge, ed. Ramsay Colles (London: Routledge, 1908), p. 325, ll. 35–6.