Dane Holt

I discovered Geoff Hattersley in 2019, after reading Wayne Holloway-Smith’s poem ‘Some Waynes’ in an issue of Poetry magazine: ‘a cavalcade of Waynes fucking each other up in a Geoff Hattersley poem – in a pub, in Barnsley.’ I was born about 30 miles from Barnsley. I mention this because I used to stockpile the occurrence of local and semi-local placenames in unlikely contexts. (There was a scene in the TV series Glee in which a New York apartment had blinds decorated with the names of South Yorkshire towns and cities like a chic reproduction of a bus route – Treeton, Doncaster, Castleton, Maltby.) So I was particularly stirred by seeing Barnsley in Chicago.

I got hold of a copy of Harmonica, published in 2003 by Wrecking Ball Press, and was hooked first-and-foremost by the look of the thing. The title stood out in reflective Frontier typeface and the cover held a deep sepia glow like an old photograph lit from behind. The face staring back from the cover was Frank, Henry Fonda’s character from Once Upon a Time in the West, holding the tell-tale harmonica. The sound of the harmonica that blows through the film’s soundscape is the past and the debt Frank owes it. Inside Harmonica, it’s the debt of successive generations and the built-in obsolescence of post-industrial South Yorkshire. In poem after poem Hattersley, or some version of him, attempts to fashion a modicum of internal space in which art might flourish. Self-preservation requires self-creation (some Geoffs) which is the heart of every Western narrative that isn’t high on its own supply of nationalism, and also the dilemma of English working-class narratives of the twentieth century.

I’d been looking for this, looking for these bridges that connect narratives and identities, circumstances and choices, so you could walk from South Yorkshire to Arizona and back again if you wanted to, without jettisoning your history or your accent along the way. In Harmonica as well as Hattersley’s other books, Don’t Worry (Bloodaxe, 1994), ‘On the Buses’ with Dostoyevsky (Bloodaxe, 1998), Back of Beyond: New & Selected Poems (Smith Doorstop, 2006), and Outside the Blue Hebium (Smith Doorstop, 2012), I found a poet who could perform the tender familial elegy, paint the portraits of working-class life and love, and remove cultural figures from one context, place them into another, and see how it plays out.

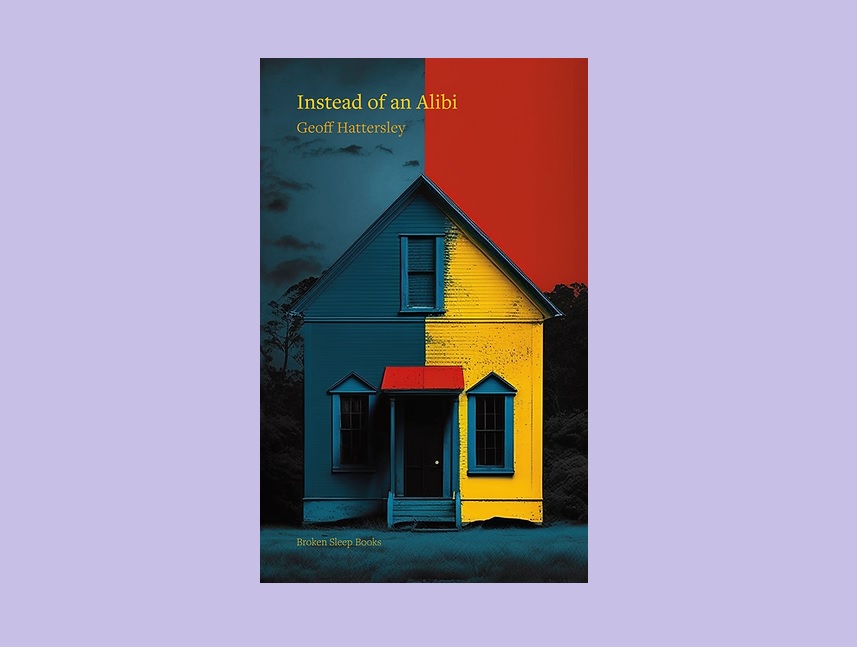

So what about Instead of an Alibi, published in 2023 by Broken Sleep Books? Well, he’s older (though aren’t we all) which brings with it a distinct quality of focus. He’s more reflective, asking questions about the value of his achievements. ‘Here’s my contribution,’ begins a line from ‘Motions’, ‘which includes poetry’. The poem is Hattersley™: the where-will-he-go-from-here opening (‘Like placing a sticking plaster / over a shotgun wound’), and the blend of the improvisatory and the polish of the well-told joke. But ‘Motions’, and many of the poems which make up the first of the book’s three sections, ‘The New Thing’, are concerned with the contribution of writing to a life as well as to a culture. Yes, the poetry of ‘Motions’ goes in the bin but it’s the recycling bin, which leaves open the possibility of continued life. A slim possibility, but a possibility nonetheless. In ‘Arthur’s in Grimsby’, the speaker’s weekend plans are in jeopardy and he might end up, God forbid, ‘with a pile of paper in front of him’ with what sounds like the tentative beginnings of a Hattersley poem on it: words like ‘mongoose, tyrant, claptrap, / pedestrian’.

Hattersley’s been around long enough to be suspicious of the ‘poetic scene’, as in the slightly sour ‘Master of Ceremonies’ (‘what tripe some of them come out with’); but the poem ends with what can only be read as an earnest request from an earnest poet: ‘Let’s have one more round of applause.’ Elsewhere he’s (slightly) less guarded. The title poem, ‘Instead of an Alibi’, shows the proof that he was where you said he was, with who he said he was with, doing what he said he was doing. Who knows, there might be something worth saving before the inevitable happens:

Flicking through his first collection

he’s surprised by a decent poem,

tucked away on page 56like a best pair of shoes

in the bottom of a wardrobe

that’s going up in flames

Section two, ‘The Nation’s Favourite Poems’, lassoes the personal and the public. There’s 1970s Blues rock shenanigans, idiosyncratic neighbours, semi-accidental acts of violence, Hollywood tough guys, and missives from the past that derail the present:

It pisses on your humour, ruins

your plans – not very grandiose plans

it’s true, but all the same something

you’d been looking forward to for some time.(‘Norman Writes’)

But there’s tenderness in there, love poems in illness and age. ‘Birthday Girl’ ends with birdsong (not a million miles from poetry, if the poets are to be believed) demanding ‘an explanation, / or offering one, / if we could only understand.’ All this culminates in the most ambitious poem in the book, ‘If’:

and if Professor Hard Times and Joe Ignorant were the Trotsky and Stalin of British politicians

and if ‘Once Upon a Time in the West’ was set in the East

and if everyone had size fourteen feet

and if a cat running up the curtains was a vital clue…

It’s a look behind the curtain of influence, Hattersley’s ‘I Contain Multitudes’. And there’s a seriousness among the frivolity, or a frivolity among the seriousness, it’s hard to tell which; but the poem’s cataloguing rhythm convinces you that with a slight shift of the kaleidoscope this way or that, a different reality might be achievable, one in which ‘this would be the nation’s favourite poem.’

The covid pandemic and successive lockdowns loom over the final section, ‘Lonely as a Crowd’. It’s some of Hattersley’s most direct poetry, with the opening of the first poem, ‘Nearly Time’, getting straight to the meat of the matter: ‘It’s nearly time for face masks / to be worn at all times by everyone’. It’s another compulsive list and, with one hell of a line break, the angle of view is slightly altered with cosmological consequence: ‘It’s nearly time for God / to find Himself in a giant egg cup, a giant spoon poised above.’ Other poems such as ‘In the Springtime’, ‘Home at Last’ and ‘Winter Lockdown Blues’ record the absurdity of lockdowns. I must confess that not a lot of pandemic poetry thrills me: maybe because so many people were driven to write poetry that described, for the most part, a fairly ubiquitous experience. But the directness of these poems clears the way for some of the book’s finest achievements. ‘I’m Geoffrey’ is allowed to be heart breaking (sometimes Hattersley can undercut emotion with a wise crack, but not here):

now he doesn’t know who I am.

Says I look a bit like his eldest son, Geoffrey.

That’s me, I tell him, I’m Geoffrey.

Don’t talk daft, tha too old.

‘No Comfort Zone’ is a fine poem that recalls another long-standing influence, Philip Levine and his poem ‘The Simple Truth’. ‘Can you taste / what I’m saying?’ Levine asks: ‘It is onions or potatoes, a pinch / of simple salt, the wealth of butter’. Hattersley’s poem grapples directly with ageing and the impulse to view things in retrospect (‘Twenty years since I did anything to shout about’), but ends with the thing Hattersley does, and has done, better than anyone in the recent memory of British poetry: a defiance that makes the desire to lie down and be counted somehow the most heroic option:

I yearn to fry an egg and a slice of white bread,

smother them in salt and get stuck in.The final poem in the collection, ‘Space’, begins

It’s not true that people like me.

OK, it’s true sometimes

but mostly not.

It’s hard to say which version of Hattersley people like or don’t like and I think he prefers it that way. There’s been some thoroughly unpleasant Geoffs throughout his career, capable of extreme violence in an extremely violent society. Others are at the mercy of love, though, and this is the lasting impression of Instead of an Alibi. The difficulty in carving out some space in what is now a post-post-industrial landscape is almost, but not quite, impossible: ‘To be with my wife is enough for me, | just to occupy the same space.’ It’s a tender moment that’s made more urgent by the stealth and swiftness with which forces of encroachment move:

She’s engrossed in The Invasion

which is, she claims, a cracking read

about the gentrification of working class areas.What gets her most is the indifference.

I think at times that’s what gets me most as well.

Times like today, yesterday, tomorrow.

Hattersley™: the direct indirectness, the humour mixed with absolute seriousness (or should that be seriousness mixed with absolute humour?).