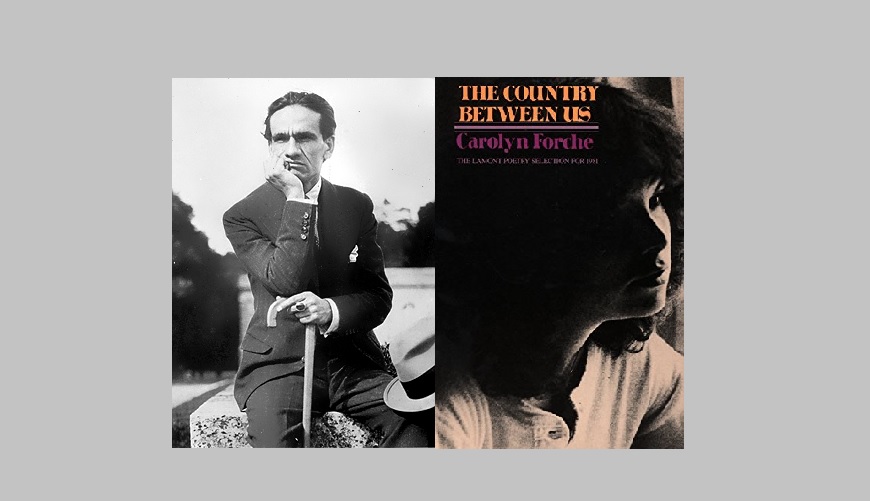

César Vallejo in 1929; the cover of Carolyn Forché’s The Country Between Us (Harper & Row, 1982)

Jonathan Hitchens

The very first couplet of A Man Passes with a Loaf of Bread on His Shoulder by Peruvian poet César Vallejo, one of the most influential Spanish-language poets of the 20th century, runs:

A man passes with a loaf of bread on his shoulder. Am I going thereafter to write about him, my double?

The answer, retrospectively, would appear to be ‘yes’, but nothing in this poem is quite what it seems. A Man Passes is a bitterly angry piece, an exhibition of youthful empathy and jaded self-examination, that viciously turns back upon itself in a final shout of helplessness. The man of the first lines, Vallejo’s ‘double’, resembles him in more ways than one. Vallejo became (or always was) one of the downtrodden; his own experiences of poverty, bereavement, and un-belonging are instrumental to his oeuvre. The poem is in thirteen couplets, all of them harsh juxtapositions:

A lame man gives his arm to a little boy. After that, am I going to read André Breton? A man shivers with cold, coughs, spits up blood. Will it ever be fitting to allude to my inner soul? … A mason falls from the roof, dies before breakfast. How then can I launch a new metaphor or rhythm?

How, Vallejo asks time and again, can we turn back to intellectual pursuits and earnest philosophical discussions so easily after witnessing the quotidian injustices around us? Under the weight of all this suffering, distractions like debate or the arts – even the act of writing his very complaint – become indignities. The penultimate couplet reads:

A man cleans his rifle in the kitchen. What good would it do to talk more about it?

Vallejo is tired of spectating on other people’s tragedies, but his chosen response is not silence. Finally, he turns towards a more comfortable reckoning with the world’s brutality: the outpouring of pure emotion; distress superseding thought. Significantly, he wonders (in the translation I have to hand) how it is possible, when ‘faced with the not-me’, not to cry aloud. To translate the Spanish literally (not by any means accurately) would be to see the poem’s last idiom, ‘dar un grito’, become ‘give a scream’. In a way, this mistranslation is almost more illuminating than a good one. Vallejo’s shame, filling the space of this poem like poison gas, demands something be ‘given’ as payment for the luxury, the privilege, of being alive and fortunate. Though not its intended meaning, the anachronism ‘cry aloud’ carries with it the shadow of ‘crying’, something that literally blurs and impedes the vision. Vallejo’s vision, conversely, is anguished in its clarity. But surely a scream, a wordless offering, is not sufficient payment?

A Man Passes is remarkable enough on the surface, but this simple poem contains hidden depths. It takes us back to a time when the entire purpose of art and creativity was being reformulated. In the interwar period, as established orders and traditions were eviscerated by the new generation of avant-gardists, equally demanding allegiances began to present themselves. The dandies and flaneurs of yesterday were well on their way to becoming the Situationists and Maoists of tomorrow. In a letter of 1932, Vallejo wrote: ‘I divide my life between political and social concerns, and my own introspective, personal concerns.’ Divided in the same way – half embracing grim reality, half wistful for the inner life – this poem stands at a crossroads. The breaking of the path into ‘introspective’ and ‘political’ also symbolises the key cultural concern of the age: artistic freedom, or the service of revolution. In the Surrealist milieu Vallejo orbited, this was evident; Breton, referenced in the poem, was caught up in the debate, joining and resigning from the French Communist Party in the space of a few months. An essay by Jason Wilson on Vallejo is useful for placing the man in his context: ‘[Vallejo] constantly dismissed book-learning, assuming the stance of the “bruto libre,” free from the burden of culture that Europeans inevitably inherit.’ (Vallejo was acutely aware of his half-indigenous parentage, which reinforced his distance from ‘Europe’.) This burden was a crippling one, however, for Vallejo not to bear: he mocked his contemporaries as essentially bourgeois individuals who ‘if asked if the sky was blue or overcast, would reach for their copy of Marx and look there for the answer’, yet he also hovered in his permanent exile on the fringes of Parisian café society.

Still, the sources of Vallejo’s conflicted state of mind can be traced far beyond politics. In a 1928 letter, he argued that ‘real self-understanding’ emerges from ‘lived experiences more than by learned ideas’ and declared, “I am not a bohemian: misery pains me greatly, and for me it is not a holiday, as it is for all of them’. In a scathing essay, he savaged Surrealism as ‘like all literary schools an imposter of life, a common scarecrow.’ All the debate and posturing was wearing thin; the “bruto libre” needed to search for truth elsewhere. As Wilson states, ‘Vallejo was no sensualist; he sought more pain, more suffering, more self-understanding through the via negativa that he chose.’ Vallejo was familiar with poverty, bereavement, and even incarceration – in many ways, life had been not so much chosen by as doggedly attached to him. A desperation is at the heart of A Man Passes: this is a man, who views the life of the street as the only authentic mode of experience, who is also a poet, compelled to express himself within the inadequacies of language. One couplet runs: ‘A banker falsifies his accounts. / What tears are then left for the theatre?’ Real life, then, is the only teacher we need, and art comes dangerously close to a ‘holiday’ for frivolous bohemians who only dare dip their toe into the well of misery. Surrealist word-games might be even more nauseating than the restrained ‘literatura de gabinete’ – ‘drawing-room literature’ – they pertained to overthrow (Vallejo condemned the Surrealist titan Paul Valéry for his ‘masturbaciones abstractas’ – no translation needed). But taking this line too far brings us up against a wall; what man of letters can really live as an anti-intellectual? ‘The word is empty’, he wrote in an essay tellingly titled Autopsy on Surrealism, denouncing what he saw as the new wave of bourgeois literature. Finding a cure for this emptiness, though, would be a far bigger challenge than diagnosing it.

At the time Vallejo was in Paris, having permanently emigrated from his native Peru, distrust in conventional methods of narration and representation – as well as primitivist ideas exalting ‘spirit’, ‘instinct’ and the like – were gaining traction. The highly influential Henri Bergson had written in 1907; ‘The most living thought is petrified by expression. The word turns against the idea and the letter kills the spirit.’ There is a fear here not just of expression, or the medium through which it takes place, but of the mental process that makes it possible, dulling the inner edge. But from this perspective, the ‘living thought’ is an oxymoron, and Bergson is really describing something closer to instinct, or, more accurately, as Michael Foley interprets, intuition: ‘intuition [for Bergson] lies somewhere in the middle of a continuum with instinct at one extreme and rational response at the other.’ Vallejo worries in his poem that his instincts are betrayed by his rationality, the two hanging apart, irreconcilable, until the very final line: ‘how can I think of the not-me without crying aloud?’ Perhaps that cry is the beginning of something, an intuition. Or perhaps, with empathy this violent, there is nowhere left to go. This poem marks a turning point: Vallejo abandoned poetry for the rest of the 1920s and much of the 1930s, almost giving up the pen completely. He would visit the USSR three times and write a socialist realist novel and a collection of militant poems on the Spanish Civil War before his death in 1938.

*

‘We’re not responsible for everything that happens to us, but we are responsible for our response to it.’ These words could have been written by César Vallejo, but they were not. They are taken from an interview with American poet Carolyn Forché, born a full twelve years after Vallejo’s death. The two poets deal, in their own ways, with the flipside of the creative impulse: the fear of speaking. Speaking, and, by extension, thinking. Vallejo faced the humiliation of failing to engage properly with the miseries surrounding him, and more immediately, the threat of political ostracisation, as the fault line between art and politics in late-1920s Paris became a gulf. What Forché faces in her poem The Colonel is even more terrifying.

Forché travelled to the then little-known Central American country of El Salvador in 1978 to work as a journalist, translator and representative of Amnesty International. In 1981 she published a collection of poems, The Country Between Us (Harper & Row), among them The Colonel, which describes a visit she made to the house of a senior officer during the Salvadoran Civil War. Here is the poem in full:

What you have heard is true. I was in his house. His wife carried a tray of coffee and sugar. His daughter filed her nails, his son went out for the night. There were daily papers, pet dogs, a pistol on the cushion beside him. The moon swung bare on its black cord over the house. On the television was a cop show. It was in English. Broken bottles were embedded in the walls around the house to scoop the kneecaps from a man’s legs or cut his hands to lace. On the windows there were gratings like those in liquor stores. We had dinner, rack of lamb, good wine, a gold bell was on the table for calling the maid. The maid brought green mangoes, salt, a type of bread. I was asked how I enjoyed the country. There was a brief commercial in Spanish. His wife took everything away. There was some talk then of how difficult it had become to govern. The parrot said hello on the terrace. The colonel told it to shut up, and pushed himself from the table. My friend said to me with his eyes: say nothing. The colonel returned with a sack used to bring groceries home. He spilled many human ears on the table. They were like dried peach halves. There is no other way to say this. He took one of them in his hands, shook it in our faces, dropped it into a water glass. It came alive there. I am tired of fooling around he said. As for the rights of anyone, tell your people they can go fuck themselves. He swept the ears to the floor with his arm and held the last of his wine in the air. Something for your poetry, no? he said. Some of the ears on the floor caught this scrap of his voice. Some of the ears on the floor were pressed to the ground.

‘Say nothing’, as the friend says ‘with his eyes’: in these two words is contained the central problem of this devastating poem. Say nothing because it will do no good. Say nothing because speaking out of turn now would have consequences. Say nothing because this is not your world, because you are just a tourist here. Say nothing, most importantly, because now is not the time. With all these reasons to keep quiet, does there remain even a single compelling one not to? Forché is extremely aware of the dangers of speech, of transgressive expression. The sentence following ‘I was asked how I enjoyed the country’ is ‘there was a brief commercial in Spanish.’ We should not assume that these are necessarily distinct moments. In fact, the only expression she is permitted within the poem is the message the colonel instructs her to carry back to ‘your people’ (presumably, the various human rights organisations Forché was writing reports and testimonies for): that ‘they can go fuck themselves’. An insult like this, apparently throwaway, serves here as the manifestation of a whole attitude, or rather the lack of an attitude, the end of a dialogue. The colonel is the largest presence here; it is no surprise that this poem revolves around a figure who threatens and mocks the existence of the very thing he is the subject of.

My reaction to Forché’s poem was slightly different each time I read through it. It demands to be reread, reheard, in states of shock, revulsion, dejection. The line that made me most uneasy every time – ‘something for your poetry, no?’ – was always the crux of it, the unchanging sneer humiliating both poet and reader, reminding us who is actually in charge, shaming us for seeking diversion, education or solace in empty words when somewhere out there civil wars are happening. But as with any work of art that necessitates more than one viewing, the poem necessitates more than one conclusion, and that line most of all. Back to the poem’s opening affirmation, ‘what you have heard is true’: it is only by the end of the poem that we have ‘heard’ anything at all. That affirmation is not just a trick to draw us in – it is Forché’s command to reconsider by rereading, to think again, this time with the knowledge she has imparted to us. Neither is it a coincidence that we have the luxury of ‘hearing’ the poem’s events, like a rumour, while the colonel displays his robbery of other human beings’ hearing organs. And so, in the poem’s final image: ‘Some of the ears on the floor caught this scrap of his voice. Some of the ears on the floor were pressed to the ground.’ Which, Forché asks, will we decide to emulate? The colonel is right – if this terrible moment were not for poetry, not for revelation, it would disappear into thin air. Instead, something is arguably recaptured from the desolation.

It is in the body that both these poems find their centre. The bulk of Vallejo’s couplets confront physical pain (‘Another has attacked my chest with club in hand. / Shall I then discuss Socrates with the doctor?’). The body is where economic and political realities hurt most. And in The Colonel, the human ears are the lasting image, with everything that they imply. They do not belong to anyone anymore, nor fulfil any purpose. For Forché, ‘they were like dried peach halves’: absurd yet familiar. Bergson’s ideal of ‘intuition’ is a reckoning with a much older duality; that of mind and body, the true home of feeling. In another Vallejo poem, a squashed spider sits motionless, close to death. ‘The poor creature has so many feet/ yet it can’t make up its mind.’ A cruel irony: an eight-legged creature rendered immobile. Even if it could ‘make up its mind’, what difference would it make? The spider suffers precisely because of the dislocation of its huge body from its head. Its ‘abdomen’, its gut (which we use as colloquialism for the deepest emotion) is the core of the problem. Are human beings, he asks, so different? Vallejo was not free from the oldest traditions, like the Cartesian, as Terry Eagleton summarises: ‘There is something spine-chilling about the intellect. A history of Western rationalism has severed it from the emotions, leaving it menacingly frigid’. Indeed, ‘from the emotions’, which originate as pure instinct – located beyond the intellect in the fragile, vulnerable body, ‘the most palpable sign we have of the givenness of…existence’ (Eagleton). The mind is an incredibly private, personal place – the body signifies to a much greater extent our commonality with the rest of the species. This is a truth articulated as far back as Shylock’s ‘hath not a Jew eyes…hands, organs, dimensions, senses’? A Man Passes is evidence of an exhaustion with new ways of seeing the world, and a wish for an essential way of feeling it instead. One couplet is particularly ingenious in this regard:

A cripple sleeps with his foot on his shoulder. Shall I later on talk about Picasso, of all people?

Though the man’s posture (‘his foot on his shoulder’) is physically plausible, it also parodies Cubist representations of the body. Both poems seek a solid foundation. Forché’s is, perhaps, the basic wrench of horror caused by looking at the results of mutilation. Vallejo also was searching for something solid that would not melt into air. He wrote, furiously:

Since the surrealist declaration, nearly every month a new literary school bursts in on the scene. Never has social thought been so broken up into so many fleeting formulas. Never has it undergone such frenetic whims and such a need to stereotype itself through recipes and clichés, as if it were unable to bring about its own organic unity… [all this] signals a new spiritual decadence: that of western capitalist civilization.

Decadence, dissolution, whim. But the essential truths of the body – specifically, the proletarian body – illness, decay, violence, and exhaustion, remain constants.

But this is where the two poems ultimately diverge. Vallejo attempts to break out of the constraints of intellectualism by building a radical empathy with strangers. Jason Wilson comments that he saw the ‘possibility of a meaningful poetry emerging from moral integrity outside the profession of literature’. In this poem real self-knowledge, and by extension real empathy with the Other, could not come from abstract philosophies nor Party slogans but from a painful, personal journey beyond the realm of the comfortable. Forché, on the other hand, is in an impossible position: she cannot assume empathy with the people she draws attention to. They have been broken up physically and narratively and are a mystery. In another interview she declared: ‘I just try to respond morally, if I can… I didn’t purport to speak on behalf of others… I didn’t try to imagine that I was one of the people in El Salvador. I had advantages. I could leave.’ Forché assembled an anthology entitled Against Forgetting: Twentieth Century Poetry of Witness in 1993, collating poems ‘from extremity’. She explains, ‘the term ‘poetry of witness’ arose out of my struggle with the cyclical argument about the poet and politics and what the poet’s responsibility is to civil society and so on.’ And the role of poetry, of any text, in all this, is as ‘evidence’:

The language is marked, the language is incised, the language is an open wound, the language is evidence. Just as much evidence as a cloth with a bullet hole in it is evidence. What we have in the literature of extremity is the way in which the human imagination has been incised.

These incisions are not without their price. In The Colonel, the price is found in Forché’s need to codify her experience, as in the line ‘there is no other way to say this’ – there is something unavoidable about the saying, but not necessarily the ‘way’ to say it. Forché presents her story in a minimalistic style, as if to demonstrate the ultimate truth of her particular way of telling it, despite the ambiguities of the final lines. She is not claiming objectivity, but something even bolder: a subjectivity that makes itself the only possible perspective. Of course, there is no right way for her to carry out the role she has chosen. Her certainty, nevertheless, is compensation for the impotence of witness, the feeling stronger in this poem even than in Vallejo’s that rebellion against the cold truth is, frankly, impossible.

Despite these muddy waters, Forché is infinitely more hopeful than Vallejo about the potentiality of language, and the relation between experience and the word. She would probably agree with a line of J.M. Coetzee’s, that ‘writing is the foe of death.’ Vallejo would not have agreed with this. To his poem, words are what the death certificate is written with. The death certificate, the philosophical tract that lifts nobody out of poverty or illness, and even the poem. But as he himself wrote:

Pessimism and desperation must always be stages along the way, not ends to be arrived at. In order to rouse and enrich the spirit, they must be enlarged upon until they are transformed into constructive affirmations.

He may have viewed certain kinds of expression as useless, but he is in a bind: even ‘crying aloud’ is another kind of human expression, and the only way it can be articulated, directed into ‘constructive affirmations’, is with that same insipid language. Wilson opines that he desired ‘a revolutionary poetics that did not betray his surrealist beliefs in inner freedom.’ This poetics, if it had ever been reached, might have been somewhere between the abdominal ‘grito’ and the murmured discussion of Socrates.

George Steiner, a writer perennially concerned with the devaluation of language, identified from the 20th century two main currents against expression: ‘the paradox of silence as the final logic of poetic speech’ and ‘the exaltation of action over verbal statement’. Vallejo eventually chose the latter course, writing:

There is only one revolution, the proletarian, and the workers will make this revolution with action, not the intellectuals with their “crisis of consciousness.” The only crisis is the economic crisis, and it has been found to be such… since time immemorial.

He acknowledged the ‘spiritual decadence’ of Modernism, but strangely seemed to decide the best answer to this would be to chuck up the spirit altogether. Vallejo’s opinion in the end can be summarised as ‘first breakfast, then poetry’; did he really have no idea that a society built on sentiments like this would have its citizens desperately searching for scraps of poetry and spiritual truth on the back of cereal boxes? Still, he was certainly prescient in his retreat from the word. The consequences for Europe’s writers after 1945 have been well documented, and that time in history leads us towards deeply difficult terrain and declarations, such as ‘no poetry after Auschwitz’. Steiner asked in 1966 whether ‘our civilisation, by virtue of the inhumanity it has carried out and condoned…[has] forfeited its claims to that indispensable luxury we call literature?’ Only the century’s victims would be able to answer him. But even if a civilisation could (it’s entirely possible that, around the time of the Iraq War, say, the West traded in its right to literature for the privilege of the thinkpiece), to demand silence from its writers would be the action of a Philistinic state. In his great love of the monolithic, Steiner predictably forgot about the individual. At the end of that essay, he swerves away from a definitive pronouncement – and if Steiner, the most blithely headstrong critic of all time, couldn’t make up his mind, what hope is there for the rest of us?

Forché tried to draw attention through her writing to not only general inhumanity, but also to her own country’s role in (and its citizens’ complacency toward) a score of Cold War proxy conflicts. From the perspective of 2020 and the infinitely self-propelling War on Terror, this problem does not appear to one willing to go quietly – and the ‘hysterical realism’ of today’s most ambitious works of literature proves that, for good or ill, the temptation is to dive into our world’s turbulence rather than turn away. ‘What you want to achieve’, she reflected, ‘is a deep attention to the world, whatever that world is.’ That world, indeed, may be a peaceful one. The Portuguese eccentric Fernando Pessoa wrote in 1935: ‘I, today, am divided between the loyalty I owe / to the Tobacconist’s on the other side of the street, as a thing real outside, / and to the sensation that all is dream, as a thing real inside.’ Both Vallejo and Forché struggled with conflicting loyalties, and each took their own paths.

Pessoa also observed that ‘to think is uncomfortable like walking in the rain’. A choice simile: both walking in the rain and thinking are immersions in, and rebellions against, the unpleasant, the oppressive, the inhuman. The responsibilities of writers are many, but they ought to agree on one thing: getting soaked is more dignified than staying indoors.