Miguel Cullen

He replied to my email saying: “I would prefer to meet you in Buenos Aires,” where I was then staying. “A distant second, New York.” I responded: “It wouldn’t be as comfortable to meet in Buenos Aires!”, almost warning him of the heady, summery, accelerated, keyed-up Buenos Aires I was in. When we meet, he says how funny he had thought that email was. He must have been going on his intuition.

Frederick Seidel is already seated when I arrive at the Café Luxembourg on West 70th Street in Manhattan, on a sunny January afternoon. He rises when I get to the table. He seems to be slightly glowing in the winter sunlight, older than I imagined (he’s about to turn 84), with a frowning forehead, gasping slightly, smiling but exuding a withdrawn intensity. His forehead, in fact, is his most prominent feature, large, clean, over a pair of blue eyes (“[m]y mother’s blue-eyed schizophrenia”) and a neat nose (“another Greek nose, in street clothes, in Harvard Yard”). He’s wearing a brown Donegal tweed jacket, a pale blue shirt and a red handkerchief in his breast pocket.

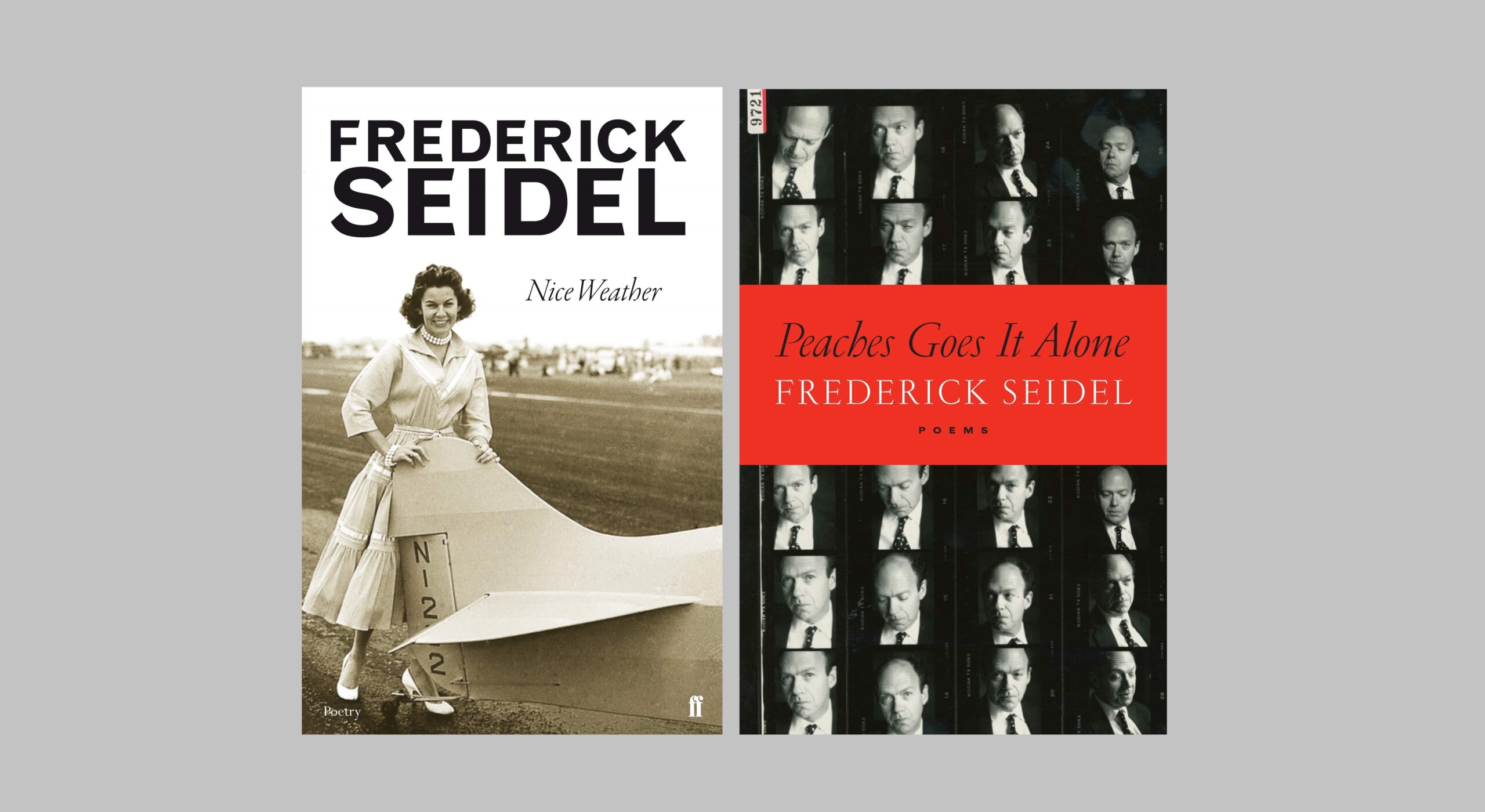

I’m nervous. I want to record the interview. He says: “No – we’re going to have lunch – for my pleasure!” He says: “Get this man a drink. Don’t worry, I know what it’s like, when your sensitivity is all over the place, but, it calluses over.” Seidel then asks me if I drink. I say not much. He says he doesn’t “during the day”. I recall to him his taste for port in the Four Seasons Hotel Ritz in his poem ‘Lisbon’ from Nice Weather (FSG, 2013).

He asks me if I found my way alright. Did I take the subway? I know Seidel likes the subway. I say I came by cab. He says “Huh huh, yes, that’s much more comfortable”, trying to bond with me slightly, although he eyes me warily, as if I’m a loose cannon. I start talking, nervous. I go on, about my experience of living in a city, how I feel tension, how I can’t get away from the closeted feeling of the dense urban life. He says “I get that”, like he’s saying: “Jeez, gimme a break! This guy is green”. Then I say that waiters in New York talk as if they have plums in their mouths, snobby, and he laughs, like a boy, out the side of his mouth.

We talk about his book Nice Weather – I go on again, say it includes many dedications to dead friends. “You mean [to say] lots of my friends are dead?” he retorts. I ask about his Harvard schooldays, reminding him how he put taps in his shoe-soles to walk loudly to writing class. He smiles dreamily, harking back. He seems gauche to be here, embarrassed, maybe, at a wrong instinct – perhaps stemming from a misreading of my poem that I enclosed in the letter to his publicist at Farrar Strauss & Giroux… As I was sitting down, he’d said: “A friend said to me ‘But you never give interviews!’, and I shrugged and said I dunno, this guy…” Now it feels like he has misgivings. “I’ve got another appointment.”

We plough on. I ask him about Wheeler’s, the fish restaurant in London’s Soho that he mentions by name in his poem ‘Fucking’ (Sunrise, Viking 1979). I mention Daniel Farson, the photographer and broadcaster, who would photograph that set: Caroline Blackwood with Cyril Connolly, Lucien Freud and Francis Bacon. Times when Seidel was the only “norm” (his term for heterosexual) in Francis’s group at the Colony Club. His eyes light up. “Oh, and Francis ….” he says, the mention of the name having brought him back to life. I’m interesting now. Phew!

I ask him about the sterling silver-plated revolver that Hercules Belleville waves around in ‘Fucking’. Recently I looked up Belleville, discovering that he was a man-for-all-seasons – a type who appears in many of Seidel’s poems: self-made, hardy yet well-read. Belleville worked in film, was always the best-dressed and the best-looking, and got married on his death bed. When I mention ‘What One Must Contend With’, his poetic demolition of a rival writer (also in Sunrise), he smiles weakly, pointing shyly at himself: “That was me!” “I know, but I hope you didn’t show it to the person you were describing?” “Yes, I did!” he replies. The sleek disembowelment was about himself.

“Do you worry about being so offensive?” He recedes into his chair, looks worried, thoughtful. “No, no” he says. “Do you care about who you offend?” I ask. “I don’t care about who I offend… I just… publish them. I’m working on a couple of poems at the moment, long ones. I had one poem published in Gray magazine, have you heard of it? They insisted on taking it, but they were shaken, you could tell they were shaken”. He looks camp-angsty. “But it was beautifully designed, with illustrations, the way it was set on the page.”

Seidel talks about psychosis, something he said his mother suffered from. “Psychosis can be a very lucid form, close to genius.” Some of the ways his poems whip around, like cut snakes, from topic to topic, and the way he seems, trance-like, to disassociate from himself, indeed his brutal and formidable aggression, seems to perhaps have come from a psychotic encounter early in life. He recounts a few times experimenting with drugs and in his poem ‘Eisenhower Years’ talks of traumatic experiences in his late adolescence, off the rails in Mexico. More recently, in the collections Evening Man (FSG, 2008) and Peaches Goes it Alone (FSG, 2018), he mentions experiences in childhood St Louis that seem to stem from a psychological wound. A Hudson Review write-up on Peaches makes this aperçu as well.

Seidel’s writing study is set high over Madison Avenue, in a large and beautiful apartment on the Upper East Side. There’s a rambling enfilade of rooms and a portrait of Eliot. “I love New York. The great thing is that you can be caught up in your work, in your room, and if you want to get away from it all, you can get out there, [gestures] into New York! To see something of New York, read the Paris Review,” he says. He was formerly Paris editor of the Paris Review and still publishes there a lot.

Our meal draws to a close. I ask for a double espresso and he says: “A single espresso for me. And give this man some crostini”. He pays the bill – $78 I think – with a platinum AmEx. His face grimaces briefly, as he swallows an after-lunch pill. When we leave I look around and he’s still inside, chatting up the maître d’. He puts on a thin green Patagonia puffer for outdoors. “You didn’t get the interview?” [pauses] “What do you care, anyway …” and roars with laughter, like we’re flaneurs – “breezing on our trust funds through the world”, to quote Lowell.

I find out later that the Café Luxemburg is his local and he often meets his interviewers there. It features in his beautiful poem ‘Coconut’:

That New York night at Café Lux when Cathy Hart was there I knew that I was not prepared, but how does one prepare? When the coconut that kills you smiles and says, Please, Fred, have a seat – And feeds you fresh coconut milk to drink and sweet coconut meat to eat. I learned it was her birthday – which meant of course champagne! I ordered up the best Lux had with my extinguished brain. Do not resuscitate the zombie under the coconut tree! It’s me on my Jet Ski painting a contrail on the blue South China Sea! Happy Birthday, Doctor Hart. You stopped my heart. You made it start. You supply the Hart part. I’ll supply the art part.

Another version of this encounter appeared in Magma, issue 56.