Matthew Stewart

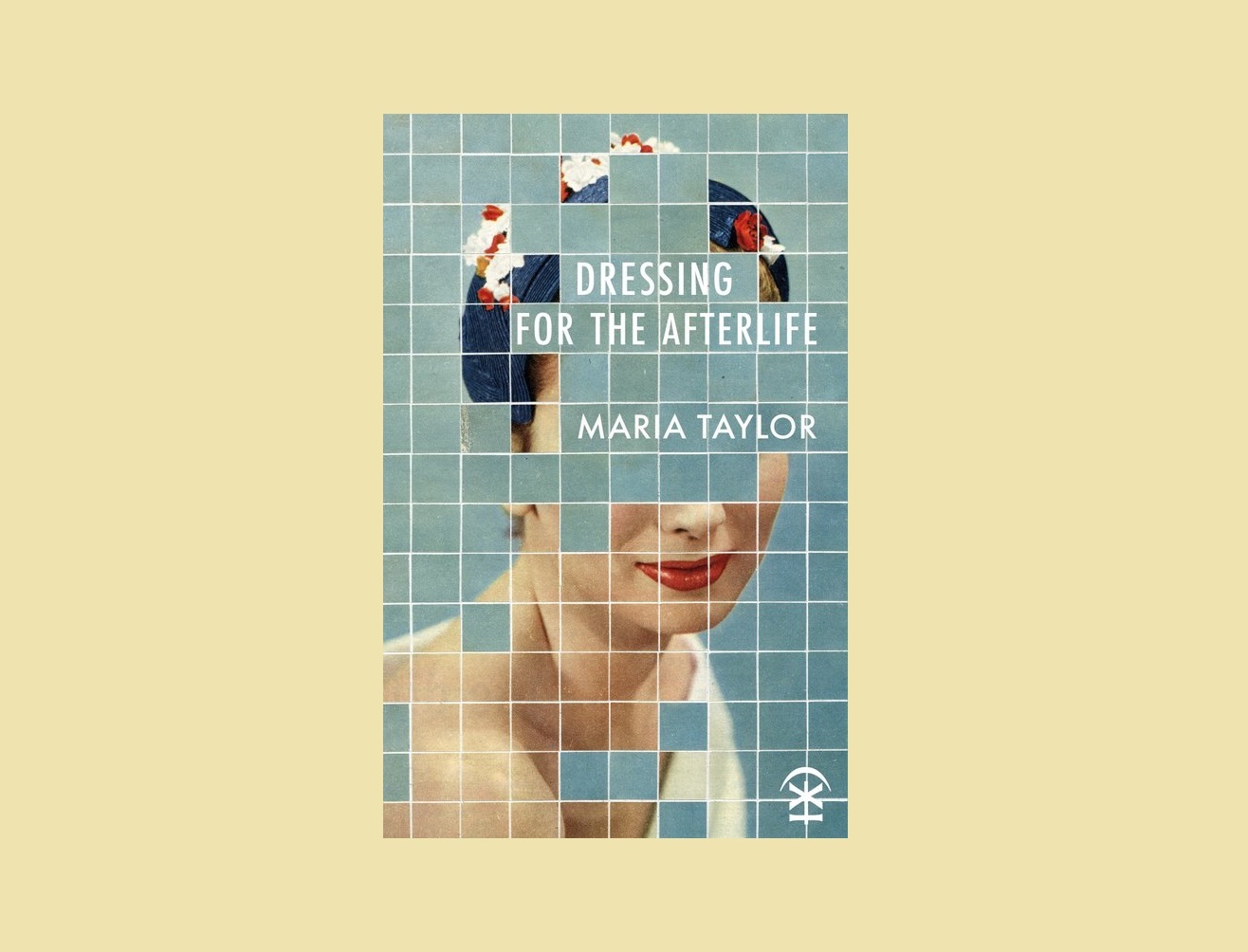

In her second full collection, Dressing for the Afterlife (Nine Arches, 2020), Maria Taylor makes a huge step forward from her already impressive first book, Melanchrini (Nine Arches, 2012). This progress is signposted by coherence and cohesion. Whether dealing with gender, nationality or family, the solidity of Taylor’s method provides a unifying force, her focus always on probing our roles and identities from aslant.

In this respect, Taylor uses cinema to great effect via its projected images of popular culture, as in the opening and closing lines to ‘I Began the Twenty-Twenties as a Silent Film Goddess’:

On the first of January I threw away my Smartphone and wrote a letter to my beau in swirling ink. I bobbed my hair, wore a cloche hat and shimmied right into town for Juleps. I became Clara, I became Louise… …Talking pictures were my ruin. At last I had a voice but no-one wanted to hear. Forgotten sisters. Oh Vilma, oh Norma, oh Mae. A musty headdress of peacock feather. Defiant silence.

This poem demonstrates that role-playing is never a form of escapism in Taylor’s work. Instead, these roles are used to cast light on our own lives. In other words, her use of surreal, impossible touches and situations (as in the opening lines in this case) is always implicitly contextualised via the real.

For instance, the ending to this poem yanks the reader back to the present in the space of two words at the beginning of its penultimate line. Moreover, in technical terms, the closing couplet is beautifully bracketed by a pair of five-syllable sentences that arrest us and lead us to the thrust of the poet’s concerns.

Perhaps Taylor’s poetry is most singular when daily and everyday experiences are portrayed as a counterpoint to the expectations that society and the media pile on top of us. One excellent poem in this vein is ‘Role Model’…

Neither Thelma nor Louise, nor side-saddled on a milk-white horse through Death Valley… …I’d like to be the woman next door with a walk that says I know where I’m going.

Taylor’s technique in this poem is first to set up a litany of supposed cinematographic role models, daunting in their actions and perspectives. By doing so, she implicitly invokes the difficulties of modern womanhood, of how shifting roles have created fresh demands. And then, of course, she sweeps the feet from under those roaming, highly imaginative lines, planting her readers back in an everyday context where the point of reference is the neighbour.

However, there are even more layers of subtlety to be unpeeled from that fabulously unassuming final couplet, as the reader is invited to wonder whether the afore-mentioned neighbour actually knows where she’s going herself, or whether she too is playing a role. Ergo, are all women playing roles? Are we all playing roles?

As the collection progresses, so these implicit questions accumulate. One such example occurs in ‘Wearing Red’, which also feels like a scene from a film…

Old enough to no longer care, a woman in a curtained room lets dark jeans fall to her feet, then zips herself into a red dress and everything it means…

In this case, the reader isn’t just being asked what the red dress means but – more importantly – for whom. Gender perspectives lie just below the surface.

Throughout Dressing for the Afterlife, the reader is witness to the unfurling of a poet whose comfort in her own skin is attained by acute self-awareness. This enables her to explore issues without the need to resolve them. One such theme is that of her national identity (the collection’s back cover describes Taylor as a British Cypriot), always approached obliquely as in the following extract from ‘She Ran’:

…I ran through my mother’ village and flew past armed soldiers at the checkpoint. I ran past my grandparents and Bappou’s mangy goats with their mad eyes and scaled yellow teeth. I ran straight through Oxford and Cambridge, didn’t stop…

Far more than a so-called ‘list poem’, ‘She Ran’ again takes the surreal as a point of departure and then roots it in the real, making points with great subtlety, as in the sudden, seemingly impossible shift in verb from ‘ran’ to ‘flew’ when passing the checkpoint. This change of gear focusses on the political ramifications, inviting us to remember that Cyprus is still partitioned, that the issue remains ongoing and painful.

And then there’s the delicate juxtaposition of Cyprus and Oxbridge, with a reminder, dropped into the following line, that the narrator didn’t stop in the latter. Of course, this sequence of moments is laden with a social significance that’s all the more powerful for remaining unsaid. Yet again, the poet is probing and questioning: where does the narrator belong?

And last but by no means least, it’s worth noting that ‘She Ran’ again possesses a filmic quality, just like so many other poems in this collection. The reader has the sense of viewing events though a camera lens. Once more, the poet is the director.

Maria Taylor’s work allows us easy access but then makes it hard for us to leave. Her poems tend to end in ambivalence, challenges and doubts, and these doubts are pivotal to an understanding of her poetry. She doesn’t aim to tie her endings up in neat packages, nor does she try to provide answers to each conundrum. This approach, alongside her idiosyncratic blending of cinematographic perspectives, lends her poetry a unique quality. For that and for the sheer humanity behind its creation, Dressing for the Afterlife deserves to be savoured.