Richie McCaffery

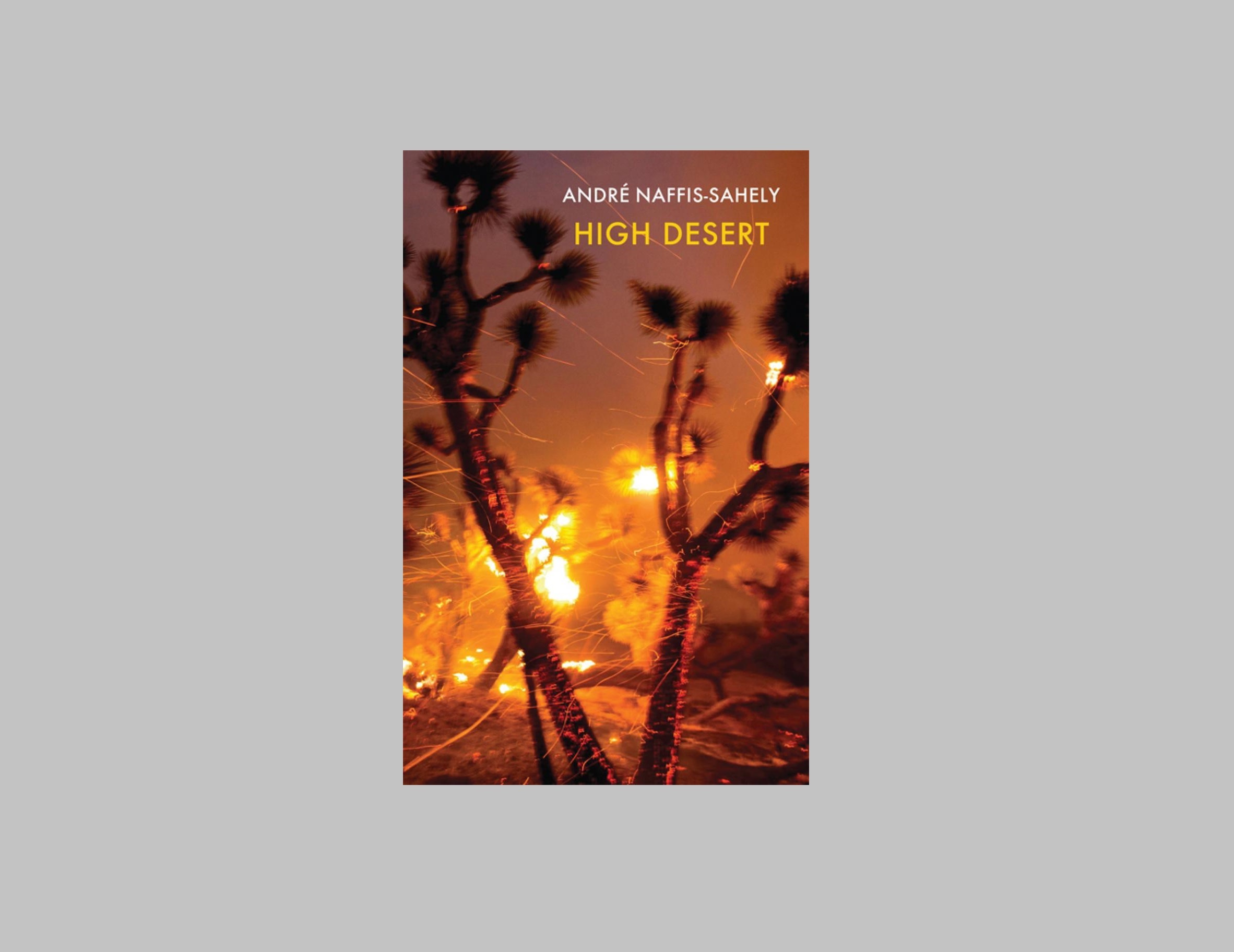

It’s been a long time since I enjoyed a collection of poetry as much as André Naffis-Sahely’s new offering, High Desert (Bloodaxe, 2022). That said, ‘enjoy’ isn’t quite the mot juste, for while there is at times dark humour here, these are unapologetically serious poems about serious subjects. Perhaps it’s better to say I was affected and struck by their moral backbone and searing honesty, than merely entertained. The desert of these poems is both a topographical and conceptual place, reached by a cosmopolitan nomad, wandering by volition and compulsion as much as necessity and out of tragedy.

A glance at Naffis-Sahely’s biography gives us a picture of a transnational writer, born in Venice to a politically exiled Iranian father and Italian mother, raised in Abu Dhabi and educated extensively in the US. The opening poem, ‘The Last Communist’, presents us with an unforgettable image of paternal and political exile, an elegy for the speaker’s father who lived to see his hopes for the world dashed around him:

I am tired of murder; each day brings a new Peterloo and all over the Earth, the fog of infallibility touches the ground and threatens to stay. IT IS BETTER TO LIVE ONE DAY AS A LION THAN ONE THOUSAND YEARS AS A SHEEP. Perhaps; but I’ll always choose to side with the flock, for I know that one day the veldt will be empty and even the lion will go hungry and die.

Fog permeates a number of these poems which are the poet’s attempts to see through all the cant and humbug of the official received history of the countries he has visited, though with an emphasis on the bloody and avaricious past of the American West. The title poem ‘High Desert’, though sounding like the melancholy ‘high lonesome’ sound of Gram Parsons out in the desert at Joshua Tree, is a fascinating mediation on the fallacy of belonging to place. The speaker argues that the desert was stolen from natives, that the whole image of the frontier town is a strip-mined facade and that what survives is sculpted in the image of greed and violence, where place names are ‘a shrine / to the seekers’ obsessions: CARBONDALE, / COPPEROPOLIS, OROVILLE, PETROLIA…’. The wayfaring speaker concludes epiphanically that is it perhaps non-belonging which is more desirable than belonging to such a questionable heritage:

Exhausted, I lie down on the sand and warm my feet by the embers of this final frontier and consider how strange it is that it’s here, where after decades of rootlessness, I abandon all cravings for permanence…

There are no easy or redemptive answers in these poems, the collection beginning in tragedy with a family torn apart and literal homelessness and ending with themes of entropy that border on the eschatological, the world facing an ecological reckoning. ‘Tule Fog’, the final poem, has a spectral bugle call that reminds the speaker of all the horrors and crimes of the past, it is a reveille, a clarion call to the speaker and reader alike to wake up, take note and strive to avoid the repetition of history.

There is something Dantean about the vision and structure of the book in its four sections, ‘A People’s History of the West’ sounding much like the tormented voices in the savage wood. Here, Naffis-Sahley devotes a found poem to various figures, constructed entirely from their own quotations, many of them being given just enough rope with which to hang themselves. Take Denis Kearney (1847-1907), described here as ‘Labour Leader & Racist Agitator’:

Our leaders have failed us and now it is time for good, honest workingmen to rid us of these gophers and vampires. […] Beware of land pirates and moneyed powers, I will not read any further from the Book of God. And whatever else happens, the Chinese must go!

What begins as a reasonable-sounding socialist viewpoint quickly transmogrifies into something much uglier. The poems are chronologically arranged in terms of the speaker’s life-dates and as the sequence goes on there is a sense of ethical evolution in people being thwarted by the obscurantists, theocrats and plutocrats in charge. Poet Muriel Rukeyser’s entry is formed from the FBI files about her being a threat to homeland security “for inciting negroes / to insurrection”. The last word is left to Tricky Dicky Nixon who is justifiably given the epithets ‘U. S. President & War Criminal’:

remember this: if you shoot wildly, the rats may get away. Why is it right? Because Communism threatens freedom and we must destroy freedom ourselves.

The section ‘The City of Angels’ exposes the bigotry, philistinism and essential Mammonism at the heart of the broken American dream. The traveller-speaker of the poems is greeted with border security on reaching the States and is given a dressing-down reminiscent of Tom Pickard in Basil Bunting’s poem ‘What the Chairman Told Tom’. Here the border force asks of the speaker:

What kind of man calls himself cosmopolitan? You’re rootless and dangerous. I’ve printed out your poems and essays and I want an answer right now: what are you doing here? Love isn’t a reason and neither is wanderlust.

(from ‘Welcome to America’)

These poems show us a first-world country that has ‘recorded the sound / the wind makes on Mars, but we cannot / listen to one another’ (‘The Year of One Thousand Fires’). The poet is naturally drawn to the creative people who have failed to fit in, such as Arthur Lee of the band Love who was ‘too white for the blacks / and too black for the whites’ (‘Maybe the People Don’t Want to Live and Let Live’). The society delineated in these poems is a dysfunctional one and it seems like only the outsider, the itinerant poet on the periphery, is capable of such an X-ray-like critical overview, diagnosing ‘a slow march to desacralisation’ (‘Roadrunners’). The speaker of these poems might be deracinated and displaced and to those in charge, he might appear powerless, but these are poems of remarkable moral heft and power, that demand to be given their place in our imaginations. The migrant is active, alert and alive, the settler merely supine. As we are told in ‘Folie à trois’:

[…] You did always say that true migrants ought to be buried upright like the Kurdish warriors of old, ever ready for battle…