Rishi Dastidar

An odd place to start but bear with. The Fence, a new-ish, waggish magazine (think Private Eye meets Popbitch) shared the following snippet in a recent newsletter, reporting the Keystone Cops-esque plotting of some various lords and ladies to ensure Brexit got done:

Obsequiousness reigns: Prins writes to Salisbury ‘Thank you, as ever, for being the indispensable Marquess.’ And what does Robert Salisbury choose for his super-secure email address? The username ‘Robert1611’ – an incongruous number, until you realise, thanks to Wikipedia, that it is a date: 1611: the year that the Cecil family built the palatial Hatfield House, where Salisbury resides today. Power to the people!

Even if you are someone for whom the city is thrill, escape and potential, when in Britain – and especially England – you cannot escape the lure, the lurking presence of the country house. How could you? So much history, so much of who we are runs under their eaves, through their landscaped gardens. The ruins and relics they are today both tourist attractions and repositories of social memory. A posit: going round country houses is almost the perfect form of recreation for the English, combining as it does walking, queuing, snooping, and property. Very expensive property.

And this is history very much alive, right now. Think of the tangle that the National Trust has found itself in as it has started to examine the links its properties have to colonialism and ‘historic’ slavery (quote marks mine, as I hadn’t considered until now the implication that someone might accuse it of being embroiled in modern slavery). This initial attempt at a fair-minded accounting, let alone reckoning, has caused a neuralgic blowback. Let’s not worry about whether or not this reaction was right (it wasn’t), but instead focus on the fact that these piles of bricks clearly still retain a symbolic power, beyond that of being sumptuous settings for Sunday night TV dramas.

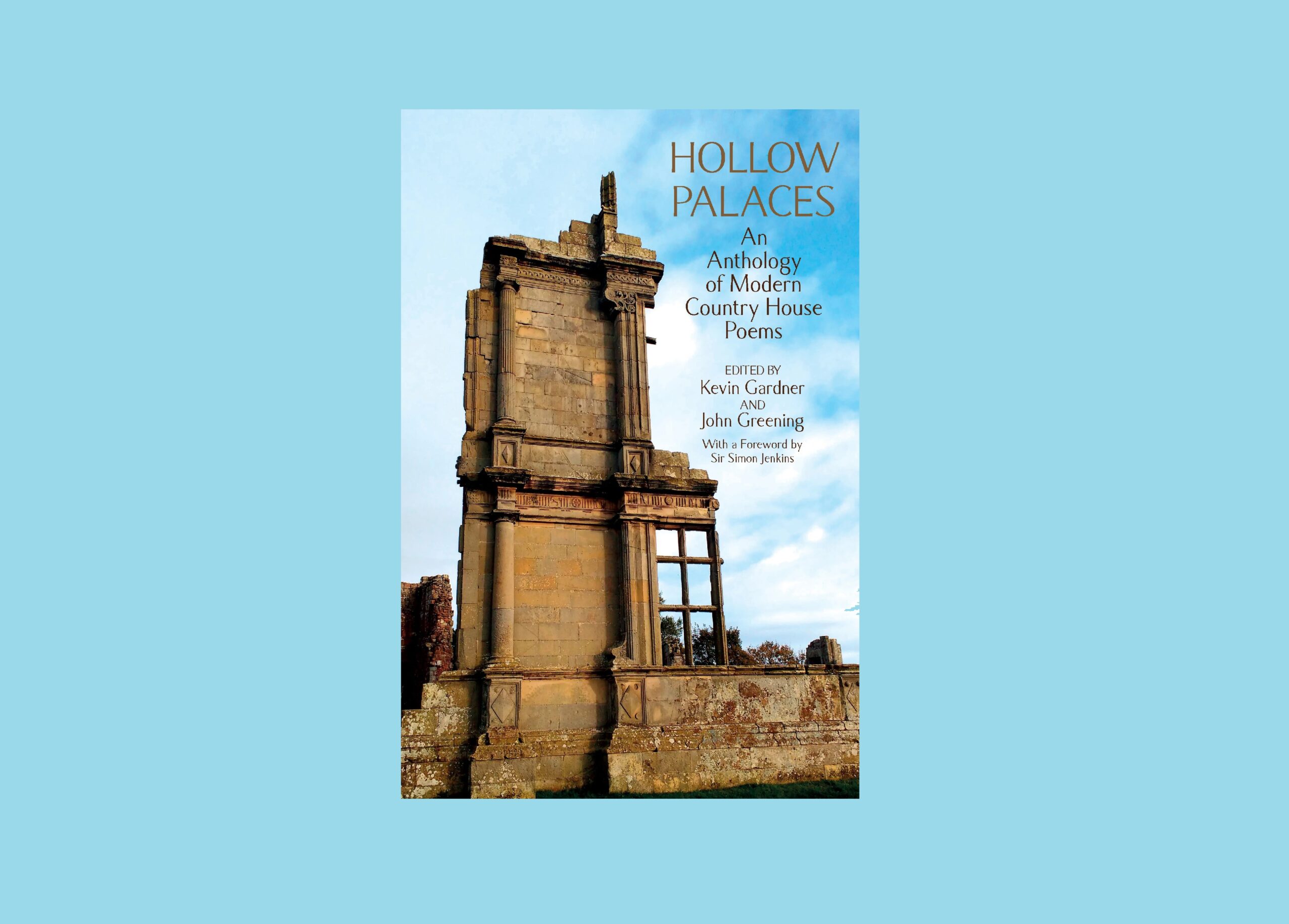

Unsurprisingly, these houses are fertile territory for poets to roam across, as documented in Hollow Palaces (Liverpool University Press, 2021). Edited by Kevin Gardener and John Greening and with a foreword by Simon Jenkins, it’s subtitled An Anthology of Modern Country House Poems, and while you might quibble with both the modern (I’ll just about allow Yeats, but de la Mare and Hardy modern?) and what counts as a country house (I zoned out at any poem about, featuring or titled ‘Rectory’ as [snobbish critic ahoy] that to me says small home not stately palace), it’s a fabulous assemblage of work that does make you think about these buildings in new ways.

What appeal does this anthology have to those of us in boxes of concrete and glass, starter Barratt homes or suburban mock Tudor villas? As it turns out, a lot. Mostly this is driven by the way the book is organised, grouped into what at first glance are surprising themes: Insiders, Ghosts & Echoes, Rites & Conversions, Fixtures & Fittings, Loyalties & Divisions, Arrivals & Departures, Dreams & Secrets, and Outsiders. What this allows for is pleasing commonalities to pop up (Wendy Cope in conversation with Yeats in Lissadell is a particular treat), as we go below stairs, explore the gothic, peel back layers of artifice and patterning, on the walls and in the gardens.

A sense of visual storytelling – visual splendour – is present in many of the poems. Is this because in part we are so used, conditioned to seeing stories set in these places, that they form an inescapable frame for a certain idea of who we are? It feels pointed that John Betjeman’s hymn to Castle Howard, Britain’s most familiar country home – thanks to the 1980s ITV dramatisation of Brideshead Revisited – opens the book: “Hail, Castle Howard! Hail, Vanbrugh’s noble dome / Where Yorkshire in her splendour rivals Rome!”

This focus on the tableaux is also in Stuart Henson’s ‘Twilight’, which mines how we think about the country house in wider culture now. It’s all here: the American ownership of these places, the behaviour you hope still happens: “The guests at the party / are guzzling, gossiping, fornicating / with reckless abandon: a dance through / the twilight of the aristocracy.” But the party always ends:

His mind fuddles. When did they start to be this huge parody, this backdrop for a costume binge shot lovingly in endless episodes and financed by the fashion industry?

Plenty of the poems showcase the beauty and the glamour, the soft power to seduce that these places have. And there are a number of poems that touch on that crime novel staple, the country house murder, full of “the green shape of a man on the dew-soaked grass” (Henson again), and the book ends with a poem from Agatha Christie too.

Inevitably there’s a stately pace to all these stately seductions – the selections are calm and measured, mostly, and then you suddenly realise, ah this is how they get you. All this beauty hiding the sources of the wealth that meant they could be built. You long for more bite. It’s there: for example in Simon Armitage’s delightfully chippy ‘The Two of Us’ and ‘The Manor’, selections from Bernardine Evaristo’s verse novel Lara, and especially Patience Agbabi’s ‘The Doll’s House’, her modern classic giving voice to the blood sugar that paid for Harewood House outside Leeds.

And we can’t avoid class. A number of the poems show us the view from outside the gates, or pressed up against the mullioned windows. I especially liked the astringency of Alison Brackenbury in ‘Wilton Park’:

Why have I never read Arcadia? Because I sensed doors in the dark. For William Herbert swept a village far out of his green and perfect park until the starving shepherds spilled back to his lawn, were clubbed and killed.

We also have to address the fact that this is – inevitably? inescapably? – a very English book. In the fifteen pages of the gazetteer of houses written about, I only counted one in Scotland, a scattering in Wales and Ireland. So when a moment arrives, such as in ‘Plas Difancoll’ where RS Thomas observes the Welsh family “speaking their language without pride, / but with no backward look over the shoulder”, it lingers.

What of the England that remains? Can it escape twitches on Robert Graves’ “thread of time-sunk memory”? You fear not. “With only cobwebs to support its bulk // a bagged and massive chandelier – / the wasps’ nest of a glass-swarm – hangs prepared / to drop at once if you should call”, writes Peter Bennet in ‘The Ballroom at Blaxter Hall’, and you can’t help but see a perfect metaphor for the nation as it is now, a geopolitical Miss Havisham, once proud and in control of its destiny, now at the vicissitudes of others. Or as JC Hall puts it in ‘Alfoxton’, “mansion of poets”: “We knock. Mortality echoes back upon / Our hearts. An impossible dream consumes.”

Close your eyes and you just about can still live the life of an aristocrat, on a slightly smaller, more intimate scale. Which is why the country house poem is still with us, will always be with us, as long as we have an unbalanced economy that allows riches to be piled up, and a culture that portrays urban living in modernist dwellings as something foreign, meaning that people with newly-minted wealth will retreat from city centres as fast as possible, and build their own palaces, WiFi’d and turreted. Who will write of the Range Rovers in the drives, and follies at the bottom of the front gardens of Chislehurst? The satirists, probably, or maybe the pop stars. Said Damon Albarn of Blur of his erstwhile record label boss David Balfe:

He lives in a house, a very big house in the country Watching afternoon repeats and the food he eats in the country He takes all manner of pills and piles up analyst bills in the country Oh it's like an animal farm, lots of rural charm in the country

Albarn should write a song cycle about the Cecil family’s role in English history next.