Charlie Baylis

Environmental poetry has made a comeback, with terror-infused natural disaster coverage and polarising climate protests riding high in the news agenda, coupled with young, idealistic spokespeople to celebrate or vilify, the environment is once again a buzz word. The resurgence in newsworthiness has fed back into poetry and revitalized a subject that has always been important, but has now shifted into something essential, as critic Jay Parini explains: “Nature is no longer the rustic retreat of the Wordsworthian poet… [it] is now a pressing political question, a question of survival”. Renewed interest in the environment has brought with it the emergence of fresh and exciting poets for whom the natural world sits at the core of their practise, poets like Isabel Galleymore, Eliza Schiff, Rasheena Fountain and Matt Howard all focus heavily on the environment, while established poets like Simon Armitage and Pascale Petit have reasserted the importance of the environment in recent collections.

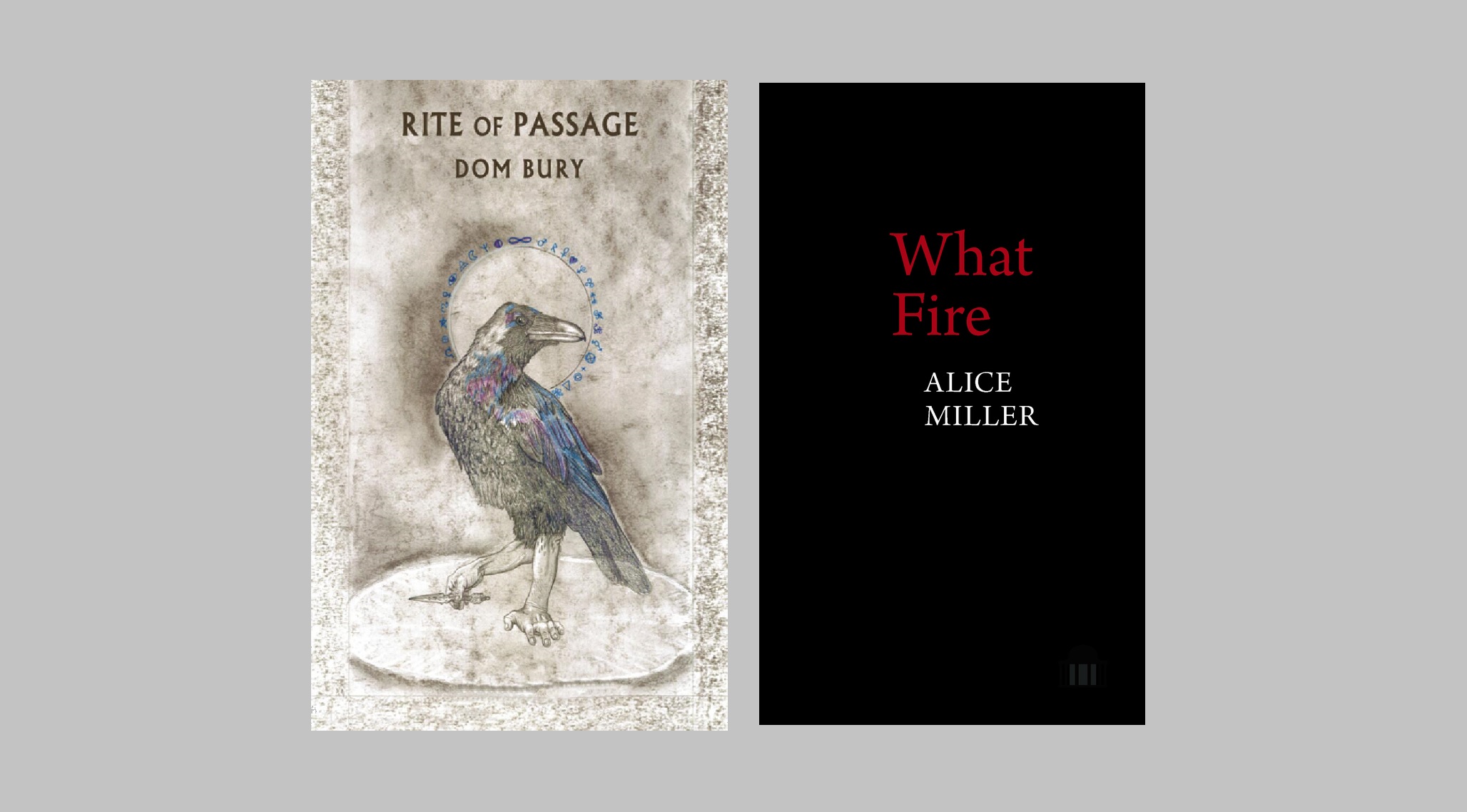

Dom Bury is a self-described ‘devotee to this green and miraculous earth’. Rite of Passage (Bloodaxe, 2021) is his first collection and contains the National Poetry Competition winning poem ‘The Opened Field’. The principal attraction of Dom Bury’s poetry may well be the violence. Bury’s vision of nature is not just white rabbits and gentle rolling hills, in ‘Hiraeth’ there is the image of the sea with ‘one white eye half-closed’ like a sinister beast lying in wait, in ‘Brother’ there is the ‘sudden hiss of magma’ and in ‘Foie Gras’ the woods are ‘shuddering as though lashed through with wind’. The short poem ‘Our Species’ opens innocently:

Two rooks in a white field -

one sings, sings the morning in,

before jolting without mercy into the harsh hues of reality:

the other

three days without food

kills

the first bird’s children

That is the whole poem – an acceleration from prettiness to infanticide in a split second. The influence of Ted Hughes is prominent. Hughes’ animals were destructive and savage beasts intent on maiming each other, full of chaos and darkness. Bury’s stark characterisation of the animal kingdom had clearly been influenced by Hughes but there is a difference in the way the two poets see the world. Bury holds out at least a little hope for the future and this manifests itself in the closing poem ‘Morning’:

To wake, now all seems possible, to step so silently to my front door then step outside into the subtle accidents of a summer morning to the new sun and the cool air lifting out from the valley

There is a sense of post-apocalyptical peace to ‘Morning’, perhaps stemming from it being a ‘new sun’, although the new is more likely a new dawn than a new central star. ‘Morning’ comes at the end of the collection, its positioning represents hope, the light after the darkness, it is a sweet and tender poem with pleasant imagery, a good way to leave the reader with something to hold out for. Hope is important to Bury, it is the silent force behind his poems – despite all the darkness, the impending mass-extinctions, wars and natural disasters, Bury remains optimistic. Hope is also important to the reader, as without a sense of uplift, his writing might be uncompromisingly bleak, trapped in a meaningless cycle of violence. So, if violence is the principal attraction of Rite of Passage, it benefits from being underwritten by hope.

Rite of Passage is a strong first collection. Bury’s self-confidence shines like the sun rising over a mountain, or moonlight over the snow, there are no weak poems but perhaps its one flaw is its verbosity. Rite of Passage is not a collection to turn to for a light read, and though there are some gentler poems, the brutality is at times overwhelming. Bury is no doubt entitled to be as bleak a poet as he wants to be, but I would have appreciated a few more leavening moments.

What Fire (Pavilion, 2021) is Alice Miller’s third collection. It features a mix of the personal, political and apocalyptical, with the environment sometimes standing in as a metaphor for individual upheaval, as in the opening poem ‘Seams’: ‘You know the earth, like your body, can’t take this.’ However, unlike Rite of Passage, the environment is not the main focus of What Fire, but a prominent one. Miller’s poems often skirt around some form of catastrophe or great ‘fire’, the end is always near, or it is already the aftermath – either way, there is plenty of turmoil both in the background and foreground. ‘Vanishing Point’ perhaps best displays the dichotomy of themes:

Ludicrous to be in love as the world ends, but that’s humans for you, I guess. The joke’s on earth, that we can still adore while dooming, I wake up with you and the world seems new.

The first line reminds me of the Lana del Rey song ‘When the world was at war we kept dancing’, though on closer inspection they are getting at different things: Del Rey’s song is about activism, Miller’s is a love poem. The romance of ‘Vanishing Point’ is plainly written; though it veers close to cliché, it is the ease of expression that makes the poem accessible. The backdrop of the apocalypse adds to the romance: who wouldn’t want to be kissing as the world explodes? Elsewhere the use of the noun ‘doom’ as a verb is interesting, the touch of a poet who is both technically astute and assured with her use of language.

What Fire bears an epigram from the Shakespeare play Coriolanus, a lesser-known play in which a mother, Volumnia, is forced to choose between saving Rome from all-consuming fire, or saving her son, the title character. Though the choices presented by climate change are not as black and white as in the play, Miller presents, through Shakespeare, one of the central dilemmas of What Fire: to what extent are we complicit in our downfall? Given the option, would we choose to save ourselves and our families, or save the wider world? There is a short poem, appropriately titled ‘Volumnia’, which delves into this dilemma:

We had no use for history but Volumnia’s. That woman against fire. That mother of a tragic son. What violence might we unleash through her line? Oh mother, what have you done? All the old songs we had nearly forgotten we now sing in the garden as we wave our torches and drink to the vastest blazes not lit to each town not yet in flame.

‘We had no use for history’ brings to mind the aphorism ‘those who do not learn from history are condemned to repeat it’; if we follow Volumnia’s line, we let Rome burn. The first point of interest in the poem is the fantastically mesmerising visual it suggests – the eternal city in flames, the Colosseum and the Fountains of Trevi licked by hellish red and amber. Meanwhile in the foreground Miller implicates the reader by using the pronoun ‘we’, it is the violence we unleash, the torches we are waving. Everyone has a hand in the fire, everyone is responsible for the flames that will come to ‘each’ town. Miller’s poetry subtly calls to individual agency and what we stand to lose by making selfish choices. Yet still, Volumnia is caught in a bind: how could she not spare the life of her son? Sometimes there are no right answers, Miller’s poetry reveals the complexity behind this unfortunate truth.

What Fire is concerned with our capacity to change while examining the world on the point of a precipice. It is successful in its aims and very readable. I enjoy Miller’s specifics, her eye for minutiae. Like Rite of Passage, it is a collection underwritten with hope; although more human and relatable, it also confronts difficult questions. What Fire and Rite of Passage are fantastic places to start if you’re looking to get some new environmental poetry. These are two bright stars of the impending apocalypse whose words will be remembered. The end is not the end, but a chance to start again.