Nell Prince

I partially recall A Shropshire Lad’s thirty-first poem, ‘On Wenlock Edge the wood’s in trouble’, because it’s in a cinematic adaptation of Alan Bennet’s The History Boys (2006). A middle-aged, wheezing English teacher, who is both relic and rebel, quotes in part reverie, part depressed mood:

The tree of man was never quiet: Then ’twas the Roman, now ’tis I.[1]

The words stayed with me. I caught myself repeating: ‘’twas the Roman, now ’tis I’ without knowing what it meant. Cinema does poetry a great favour in this respect: a fragment quoted lodges in the brain.

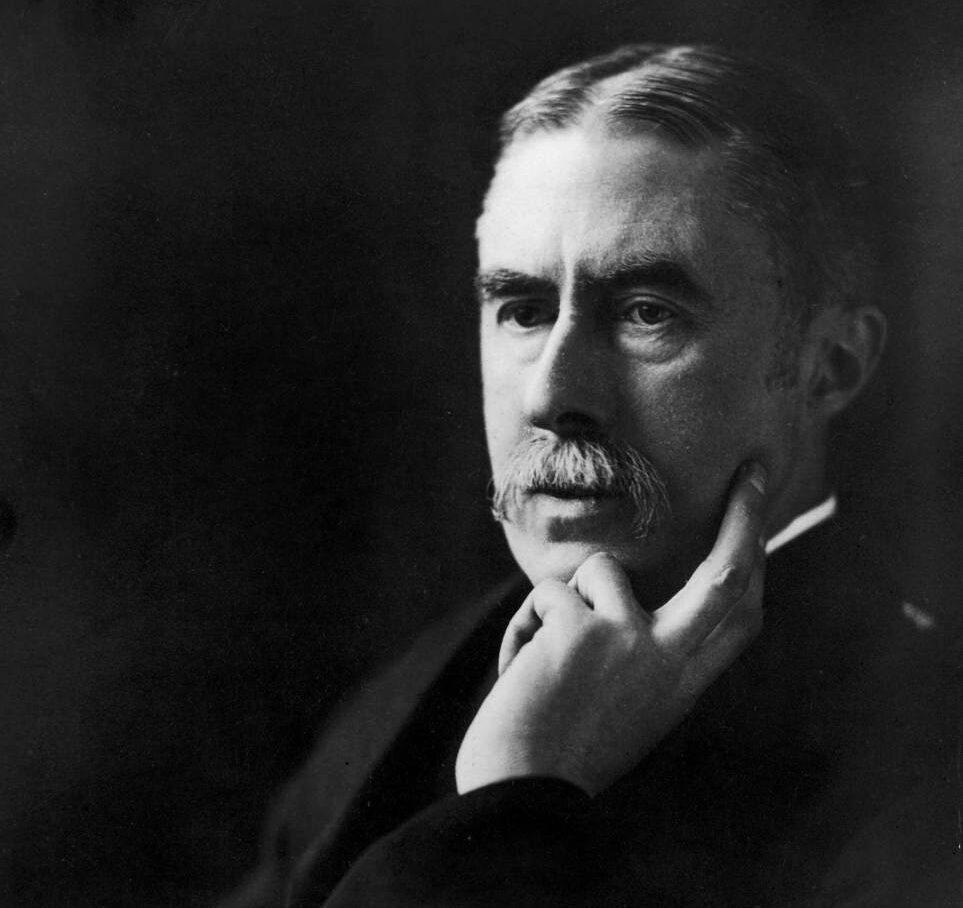

Published in 1896, A.E. Housman’s A Shropshire Lad has come to represent quintessential ideas of Englishness. There are both rural scenes – ‘oh see how thick the goldcup flowers / are lying in the field and lane’ – and urban imagery: ‘When smoke stood up from Ludlow, / And mist blew off from Teme’. Many of the poems have an obvious metrical clunkiness (see ‘XXI Bredon Hill’) and are often seasoned with sentimental feeling (see the first poem ‘1887’ for celebrations of Queen & Country).[2] Actually, though, the more I read A Shropshire Lad, the darker it gets.

The highs and lows of this classic collection of sixty-three poems are arguably best read through a twenty-first century queer lens. When Housman studied Classics at Oxford, he fell in love with Moses Jackson, and botched his final exams. Jackson was heterosexual and did not return Housman’s feelings; after Oxford they lived together in London from the late 1870s until 1885.[3] Thereafter they had little contact, and Housman, it seems, was uninterested in other men. Charles McGrath writes:

More than half of A Shropshire Lad was written during a charged five-month period in 1895, when Housman seems to have been missing Jackson acutely. Readers with advanced gaydar, like Oscar Wilde and E. M. Forster, early on detected a note of suppressed homosexual desire.[4]

There was a crisis; Housman never moved on from Jackson, and this is perhaps reflected in his focus on unrequited or lost love. ‘XIII’ in A Shropshire Lad is similar to Yeats’ ‘never give all the heart’; ‘XIV’ muses on ‘drowned’ heart and soul; ‘XVI’ talks of ‘the lover / that hanged himself for love’; and ‘XVIII’ is a brief poem which begins ‘Oh, when I was in love with you’. This is in the context for the poet’s real tenderness for men in his work. His obsessive use of the word ‘lad’ in the collection occurs over 40 times, indicating youth, vulnerability, and perhaps local Shropshire dialect. The word ‘boy’ is more familiar, less countrified. He is always in sympathy with the lads who go to war (poem ‘I’), lads as victims of their social context, lads out of luck or love.

McGrath reads a later poem, ‘XLIV’, as a reference to the case of Henry Maclean, ‘a young soldier who shot himself in a London hotel, apparently out of homosexual shame’.[5] With homosexuality illegal in England, there was good reason for Housman to disguise his work with the idyllic English imagery he is associated with today. This association is a little difficult to understand given the number of dark turns in almost every poem. ‘XLIV’ is political and angry and reminds me of Blake’s ‘London’ because of how it notes the cyclical nature of social injustice:

Souls undone, undoing others, – Long time since the tale began. You would not live to wrong your brothers: Oh lad, you died as fits a man.

Housman’s doesn’t have quite the elegance of a Blakean stanza, but there is a real cry of anguish here which helps generate the poem’s momentum. ‘On Wenlock Edge’ stands out as a poem equal to the best of Blake. There is a greater objectivity at work; Housman’s usual sentimentality is absent and this gives the poem its weird heft.

The first line begins: ’On Wenlock Edge the wood’s in trouble’. This has a sharp ring about it for the contemporary reader, in the ecological sense. It is both localised – ‘Wenlock Edge’ – and universal: ‘the wood’s in trouble’. ‘Trouble’ is the most important word – dramatic tension established to pique our curiosity. Here is the stanza in full:

On Wenlock Edge the wood’s in trouble; His forest fleece the Wrekin heaves; The gale, it plies the saplings double, And thick on Severn snows the leaves.

The notion of a forest being a ‘fleece’ for a personified hill – in this case the Wrekin in Shropshire – is an unusual one, but ‘the gale’, beginning the third line, helps the metaphor along, and we are left with a lovely image of ‘And thick on Severn snow the leaves’. The autumnal setting creates a quiet context of melancholy, but this is only backdrop. Housman picks up that leaf-strewing ‘gale’ again in the third stanza, blending the melancholy with an albeit muted ‘anger’:

’Twould blow like this through holt and hanger when Uricon the city stood: ’Tis the old wind in the old anger, But then it threshed another wood.

‘Uricon’ refers to Viroconium or Uriconium – a Roman town, now called Wroxeter, in Shropshire. It sounds and looks like ‘unicorn’, which might explain the word’s mythological power compared with Uriconium – too heavy and Latiny for the poem’s sonics. ‘Uricon’ is also an interesting break from the rural; an almost-vanished Roman city, its presence indicates how past informs present. It sets up the semi-parallel in the last line: ‘But then it threshed another wood’, which brings us right back to the start of the poem: ‘On Wenlock Edge the wood’s in trouble’. Landscape is forever in flux; cites rise and fall.

But what is really special is ‘the old wind in the old anger’ – special because it is memorable and, in some deep sense, true. In comparison, the poem’s third stanza feels clunky. ‘Yonder heaving hill’ strikes me as slavishly old-fashioned even for a late nineteenth century poet. It has a clumsy Miltonic grandeur which isn’t helped by the third line: ‘The blood that warms the English yeoman’. Perhaps because I have not been made to care about the ‘English yeoman’, I am not struck by the ‘thoughts that hurt him’. But I can see how useful this less exciting stanza is to the next; the Roman and the English yeoman tee us up for the idea of inheritance:

There, like the wind through the woods in riot, through him the gale of life blew high; the tree of man was never quiet: then ’twas the Roman, now ’tis I.

There is a slight note of sentimentality in ‘through him the gale of life blew high’ – the metaphor feels a little stretched. But pause too much on the imperfection and we miss the really good stuff. Without that line, we wouldn’t get ‘the tree of man was never quiet’, which is absolutely, profoundly true and brilliant. A contemporary reader may hesitate at the poet’s determination to see the world entirely in terms of ‘man’ but, if nothing else, ‘man’ is syllabically far more convenient in terms of metre than ‘woman’. We can take ‘man’ in the universal sense, but as A Shropshire Lad is so lad-centric, and explorative of repressed homosexual desire, it is doubtful that was only what Housman meant. And although ‘On Wenlock Edge’ feels like a one off – attaining a higher level of brilliance than the other poems – it can also be read, I think, in the gay men context. The wood that’s in ‘trouble’ might allude to an inner struggle.

‘On Wenlock Edge’ suggests continuity but also perhaps no human progress, and that is the crux of the tragedy, an ossifying of free choice and agency. Here is the last stanza:

The gale, it plies the saplings double, it blows so hard, ‘twill soon be gone: To-day the Roman and his trouble are ashes under Uricon.

‘Saplings’ is a recycled line from the first stanza, quietly inserted to regain the original rhyme of ‘double/trouble’ – and one is tempted to see this as an allusion to Macbeth, particularly as ‘Wreckin’ refers to The Wreckin hill in east Shropshire, recalling the ‘heath’ where the three witches meet in Shakespeare’s drama.[6]

Housman in fact wrote A Shropshire Lad whilst living in Byron Cottage, Highgate. It is most likely, then, that Macbeth was on the poet’s mind considering Hampstead Heath would have been a frequent place of visit. Parts of the heath are exposed land where the wind certainly ‘plies the saplings double’. The poem, though, is far away from a nineteenth-century London context in feeling and tone. It does have a playwright’s dramatic tension within the words; Wenlock is personified, so too the angry wind.

An anomaly, then, ‘On Wenlock Edge’ – a poem which is particularly guarded, more furtive than most of the tragic, queer pieces in this homoerotic collection. This poem escapes a readily-identifiable political context. This is in contrast with A Shropshire Lad as a whole. Far from being a sappy sermonising on Englishness, Housman skewers happy-go-lucky notions of idealised rural or urban living, and whenever I find a poem approaching the nationalistic, there is too much subtle irony and sarcasm to have it pinned as such (see ‘XXXIV The New Mistress’ where the ‘dropping dead lie thick’ feels like a critique of the potentially jingoistic ‘enemies of England’). A Shropshire Lad is the work of master craftsman writing in the late nineteenth century but – as we search for what Englishness means in the twenty-first – as relevant as ever.

[1] All Housman quotations taken from Housman, A. E, A Shropshire Lad. Cambridge, England: Silent Books (1995).

[2] This is somewhat contentious. ‘1887’ can be read as a thoroughly sarcastic attack on nationalistic warmongering with real empathy for the lads who have no choice but to fight.

[3] Housman’s relationship with Jackson was dramatised by Tom Stoppard in The Invention of Love (1997).

[4] Charles McGrath, “How A. E. Housman Invented Englishness,” https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/06/26/how-ae-housman-invented-englishness (The New Yorker, June 19, 2017), https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/06/26/how-ae-housman-invented-englishness.

[5] Ibid.

[6] For more on this see: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/27/books/review/a-e-housman-country-biography-peter-parker.html