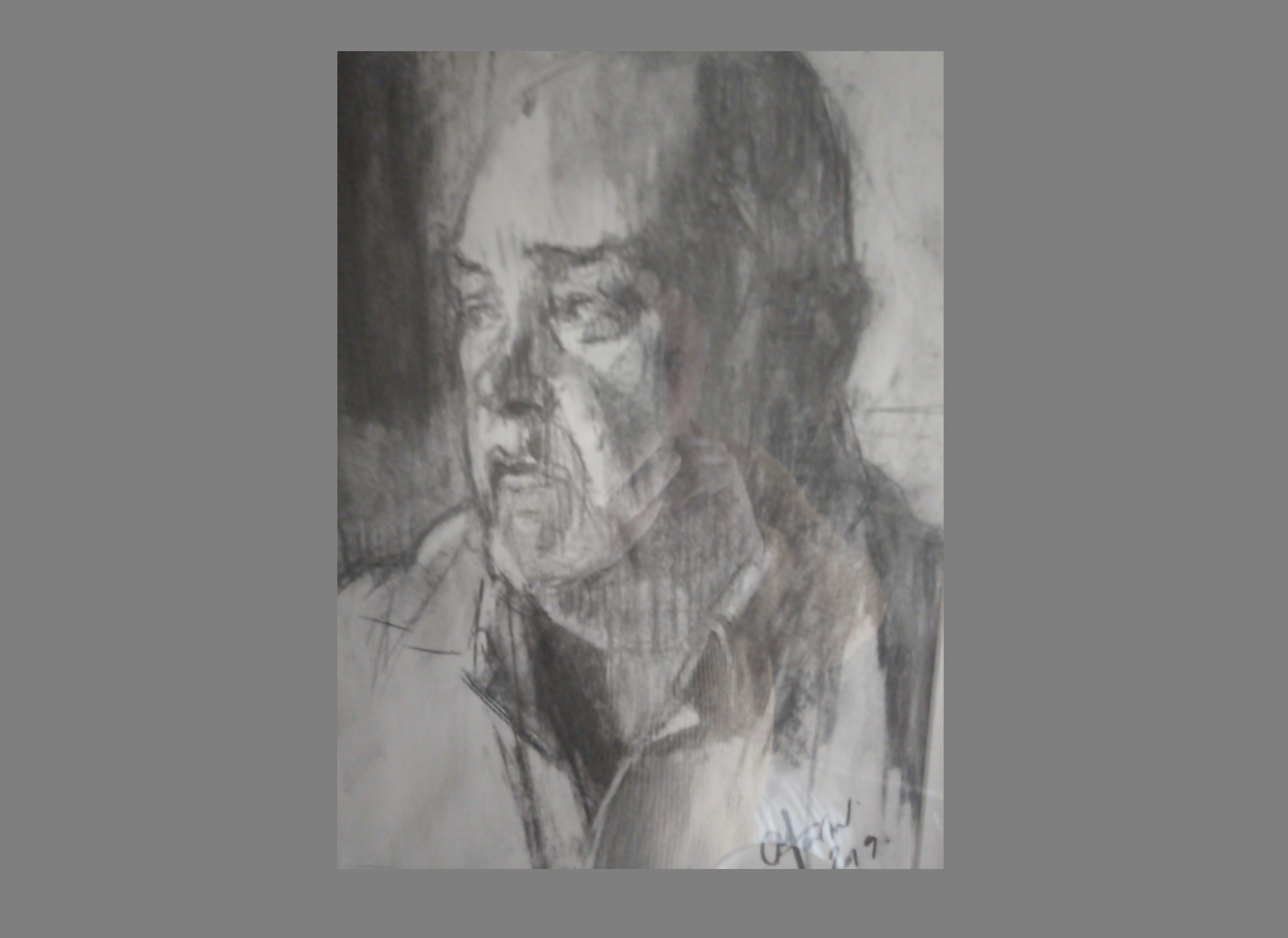

Portrait of Ian Parks by Andrew Farmer

Ian Parks was born in 1959 and is the author of eight collections of poems, including Shell Island, The Exile’s House, Love Poems 1979-2009 and Citizens. He is editor of Versions of the North: Contemporary Yorkshire Poetry and the Selected Poems of Harold Massingham, and his translations of the modern Greek poet Constantine Cavafy, published by Calder Valley Poetry, were shortlisted for the Michael Marks Award.

Ian has been Writing Fellow at De Montfort, Leicester and writer in residence at Gladstone’s Library. He currently runs the Read to Write Project in Doncaster. Below he talks with Tuesday Shannon about this project, plus the communities and poetries of Yorkshire and the north, Chartist poetry, his own poetry career and his forthcoming Selected Poems. Two accompanying poems by Ian are up on Wild Court here.

(Tuesday Shannon) You’re quite well known for your love poems, yet your last two collections, The Exile’s House and Citizens, centre more on themes of identity and geography. Is this a conscious shift in focus?

(Ian Parks) I have always written love poems, but they were interspersed among several collections until 2010 when Love Poems 1979-2009 was published and gathered together all the love poems I wanted to preserve up to that point. I say ‘up to that point’ because I continued to write love poems after that and still do. Although there are love poems in the two collections you mention you’re right to notice a shift from the particular to the universal and from the private to the public. It’s a tension Auden explores in his love poems from the 1930s. I think, with hindsight, the shift you talk about was a deliberate one. I felt that I’d pretty much done all I wanted to in the genre and was in danger of sounding like myself! In theory I could have gone on writing Ian Parks love poems until the day I died – but there were more pressing issues I wanted to address.

What pressing issues? Was there anything specific that led to this shift from the private to the public?

There was. In 2010 the inconclusive general election led to the formation of a coalition government in which power was supposedly shared between the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats. It seemed to me that it spelled the demise of the intellectual left. The Labour Party had effectively divorced itself from its radical roots by then. I’m thinking of statesmen like David Owen, Paul Foot, and Peter Shaw who were socialists and intellectuals also. For them the two were connected: any person of intelligence and compassion would draw towards socialism. I don’t want to get into the details of the political situation a decade ago – except that it played a part in my shift from private to public poetry. It made me think of the great radical tradition which, being the son of a miner, I was born into. And so, it was that I wrote poems about what Andy Croft described as my ‘places of painful historical memory’ – and particularly the Miners’ Strike of the mid 1980s in which I took an active part. But there were also poems about the Levellers, the Chartists, the Great Trespass, and the Jarrow March. I was testing poetry to see if it could carry that kind of political weight and I still am.

Looking at the 2010 GE result now, with the benefit of hindsight, that inconclusive result could be seen as an exacerbating factor in many current social divisions. One of those that seems particularly relevant here is the English North-South divide. The British ‘poetry scene’ is often considered quite London-centric. How does your location (and indeed your heritage) in the North feed into your work?

I think the North-South divide exists in the arts and in society in general. It has to do with cultural perceptions, yes, but those perceptions have developed for a reason. When I edited the Yorkshire poetry anthology Versions of the North in 2013, I wanted to demonstrate just how distinctive contemporary Yorkshire poetry is – and how vibrant. What I discovered as the poems came rolling in was that the main themes were landscape and belonging and, overwhelmingly so, conflict. Not just conflict in the North itself but, primarily, with the South too. I certainly think of myself as a Yorkshire poet writing out of and for a specific community but feeling my job has been done properly when it has been ‘overheard’ and acknowledged by others. I suppose my poem ‘The Great Divide’ attempts to address those tensions and to explore how they might surface in poetry. Mexborough has helped with that. It has been, poised as it is on the north bank of the Don, a border town, a frontier town, and a place of strategic importance. Ted Hughes and Harold Massingham walked its streets and the countryside around it, and they knew that too.

To what extent do you feel you belong to that Mexborough community? There is a lot of tension around that matter in some of your poetry.

Jesus supposedly said ‘a prophet is never welcome in his own hometown’ – although the inhabitants had just tried to throw him from a cliff! I feel very strongly connected to the community I was born into and am still living in Mexborough. I think poets need to have some sense of an audience even if, in the first instance, that’s only an audience of two or three people. My imagined audience has been the people I live amongst and see every day – although the evidence would suggest that very few of them have read my poems. Education changes you and so does poetry. Tony Harrison understands that and it informs every page of The School of Eloquence. And yet poetry arises out of tension and is driven by paradox. I would like to think, in some sense, that I am articulating in poetry views that are pretty generally held by the community I live in but which they choose to express in another way. I don’t always succeed in that but in poems like ‘The Wheel’ and ‘Standards’ I think I do.

Are those poems especially important to you – the ones in which you feel as though your sentiments and those of the people you write about are closely aligned? And how do the people of Mexborough express, say, a desire to roll the disused pit-wheel at the cities of the south, as you put it in ‘The Wheel’? I tend to regard that poem as a reminder to those who might not remember the desecrations of the period that led to the removal of the wheel.

‘The Wheel’ is a seminal poem and you’re right to identify it as such. You’re also right to suggest that the poems that have arisen out of my response to the working-class community I was born into are important to me. I suppose they are, in some sense, a record of my struggle to find a language which can carry the weight of that experience. I think of those poems as being not so much ‘for’ or ‘about’ the people of that community but ‘by’ them in the sense that they arose from a common, shared source. The poems are a way of voicing that. The tensions that exist there exist with the overlap between public and private poetry. No poetry is entirely private, and no poetry is or can be entirely public although the themes it deals with might be considered as public. My public poems are really to do more with social justice than politics. The Wheel serves as a reminder – to myself as well as to my audience – that the question of social justice (and injustice) is something that is more important now than ever. We all have a responsibility to ensure that the new reality we emerge into after the current crisis is a fairer one than we left behind. Poetry can be central to that struggle.

Speaking of your community, you run a project called Read to Write. Could you say something about that?

Gladly. I started Read to Write in 2016 as a grass roots poetry movement based in the Doncaster region. People kept telling me that there was no appetite for poetry in such a depressed area where engagement with the arts was low. Within a year we were putting on rehearsed readings of Shakespeare’s sonnets to packed audiences in local venues. Under the normal conditions the group meets twice a week and I present a taught session followed by a workshop in order to keep the reading and writing balance stable. I have been ambitious, teaching Beowulf, Paradise Lost, and The Waste Land to large groups. We have been on the road too, performing at pubs, at railway stations, in art galleries, libraries, and parks. All of which shows that poetry is not the preserve of a privileged elite and is alive and well in the hearts of everyone who is allowed to be exposed to it. The government are currently encouraging young people not to become artists at the very time when we need them most.

How has your education changed you? The three poets you’ve mentioned – Tony Harrison, Ted Hughes, and Harold Massingham – all received grammar school educations. Do you think it’s harder for working-class kids in state schools to get ‘into’ poetry?

I don’t think there’s anything in particular to stop anyone from getting into poetry. If you want to be a poet badly enough and if there’s a real sense of calling then it will happen. I can’t remember a time when I didn’t want to be a poet. A degree in English Literature will introduce you to some great poetry and will provide you with some useful ways of thinking about it but it won’t in itself make you a poet. That is a matter of sensibility rather than education. I was very lucky. I started out as the son of a miner and ended up researching Chartist poetry in Oxford under Raphael Samuel. I’m not entirely sure that it could happen now – and certainly not in the same way. The great tide of equal opportunity has come in and washed over us and all the evidence shows that it is going out again.

What was it that drew you to Chartist poetry specifically?

The Chartists were the first mass popular working-class movement thriving in the middle decades of the nineteenth century. Their main aim was social improvement through change in the electoral process at a time when only a tiny minority of privileged individuals were allowed to vote. What interested me primarily was the fact that they saw poetry as performing a function and that they chose it as a medium in which to express their political ideas. The Chartist poets – Ernest Jones and Thomas Cooper in particular – had massive audiences which, in itself, casts a question mark over the received idea of working-class illiteracy. I tried to deal with some of these tensions in a long poem called ‘Elegy for the Chartist Poets’ which closes my Citizens collection. Poetry as a force for change. There’s a thought.

You recently published a selection of Cavafy translations. What brought you to that project?

You couldn’t find two poets more different than Harold Massingham and Constantine Cavafy. I first encountered the latter through W. H. Auden who drew attention to his ‘unique tone of voice’. He also said something about his poems ‘surviving translation’ which intrigued me. There are some good translations out there but I felt they were too literal and that the ‘atmosphere’ of the poems was lost somewhere in the mix. And so I resolved to teach myself modern Greek – at least to the extent where I was able to capture some of the nuances of the originals. I have produced versions of sixty of his poems out of a canon of around three times that number. I simply stopped when I had engaged with all the poems I felt I could bring something to in terms of technique and sensibility. I was drawn to the fact that Cavafy was a very private poet who actively avoided the limelight. Most of his poems were distributed among his friends in handwritten copies. That approach seemed such an antidote to the career poets you encounter all the time where more energy goes into promoting their poems rather than writing them. Cavafy wrote about the classical past but he also wrote exquisite lyric poems about love and loss. Again, if you haven’t read him then he is well worth a look. I’d like to mention Rory Waterman at this point who encouraged me in this project by publishing the first of my versions in New Walk Magazine.

It’s a beautifully done project. How was it for you working with translation rather than working with your own lines and ideas?

Thank you. Once I had the gist of each poem I was then able to refract it through my own voice. My poetic sensibility is quite close to that of Cavafy so it wasn’t a strain to reach for his effects. And he approaches a love poem in the same way, through specific situations rather than generalisations. He recreates certain moments of emotional intensity without telling us about them. A critic pointed out that Cavafy was homosexual and I’m not. Did it, he wondered, make any difference to me when I was writing the love poems. To be honest it never crossed my mind. The love poems are about love and not about gender issues. Yes, he does talk about illicit sex but heterosexual relationships can be illicit too. His poems have a piercing quality to them. No one else – with the exception perhaps of Hardy – writes so movingly about love and loss.

You’ve published with a number of small imprints throughout your career. What draws you to independent publishers?

I know that the received wisdom recommends that you find a publisher and stick with them but if you write a lot – and I tend to – you might have to wait a very long time, years in fact, before your poems appear in print, by which time you’ve moved on. I’m drawn to independent publishers because they are, after all, professionals. The big outfits generally publish fiction and other genres too and poetry forms only a small and highly subsidised part of their list. If you’re working with, say, Bob Horne at Calder Valley Poetry or Andy Croft at Smokestack books, you are dealing with dedicated people who have a passionate love of poetry. I know that publishing in that way can be a risky business – and I’ve never been averse to risk. I’m very lucky that Simon Jennet at Waterloo Press has just reprinted The Exile’s House from 2013. Independent publishers are the lifeblood of poetry. That is where the truly exciting things are happening and where I want to identify myself as a poet.

Your Selected Poems is due out soon. Why have you decided to do this now?

It is turning out to be a long process because whenever I think it’s ready, I bring out some new poems which I feel ought to go in. The problem at the moment is deciding what to leave out. In many ways a Selected is the most important collection of a poet’s career because it represents the whole broad sweep of it. And it isn’t necessarily a simple matter of including your best poems – because your best poems aren’t necessarily the ones that show your scope and range. And then there’s the question of revision. There are some early poems where I can see now exactly what’s needed to recover them. Faced with that dilemma do I revise or remain true to my younger self? Invariably I stand by the integrity of the poem as it stood when it was first published. Presenting the poems in chronological order will hopefully allow the reader to trace the kinds of changes and shifts in emphasis that you have discovered. I shouldn’t complain. I’m lucky to be in a position where I can choose. A position where I can put a Selected together in the first place.