Ruth Padel:

It was a great pleasure, this May, to go to the 4th Miłosz Festival, in honour of one of the twentieth century’s greatest and most iconic poets, in Kraków, the city to which Czesław Miłosz returned at the end of his life, and an enormous honour to give this lecture there, the very first Miłosz Lecture. I was also lucky enough last year to visit the Borderlands Foundation in the Manor House at Krasnogruda by the Lithuanian border [http://borderlandatlantis.net/borderland-atlantis/krasnogruda/]: an intensely beautiful, intensely green post-glacial landscape of hills, lakes and forests, where his mother’s family came from. A place of racing clouds and bright lakes, ruffled by waves,

A place of racing clouds and bright lakes

A place of racing clouds and bright lakes

outside the town of Sejny where the bishop and poet Antanas Baranauskas wrote the poem Anyköčiu öilelis [The Anyköčiai Grove] and where there was a famous school and printing house. Miłosz grew up in rural Lithuania, but all aspects of Krasnogruda were formative influence too.

He knew it first as a pupil at Zugmunt August secondary school, then as law student at Vilnius University. He stayed at the manor house in holidays with his beloved aunts, Ela and Nina Kunat.

He visited his parents and brother in nearby Suwałki, swam in Lake Wigry, had his first love affairs here. Then at 29, in 1940, he escaped through it – getting out of Vilnius, just occupied by the Soviets, to East Prussia and then Nazi-occupied Warsaw.

When he was able to go back, in 1989, he called it then, reticently, a place “of many contradictory experiences,” And said he “did not expect such a gift from God as these days here.” The park had grown wild. “I forced my way through a thicket where a park was once,” says his poem Return. “But I did not find traces of the lanes.” He was almost eighty. “On Wigry Lake, at last I had a feeling of return.”

I’d like to hold in mind that green landscape, his words contradictory and traces, and also a photo I saw of him in that house: nearly eighty, sitting down doing that act we all share, and for which we honour and thank him today – writing.

I shall follow five of his poems, starting from 1933 when he was 22, then on to 1943 when he was 32, and on to 2003 when he was 92.

I

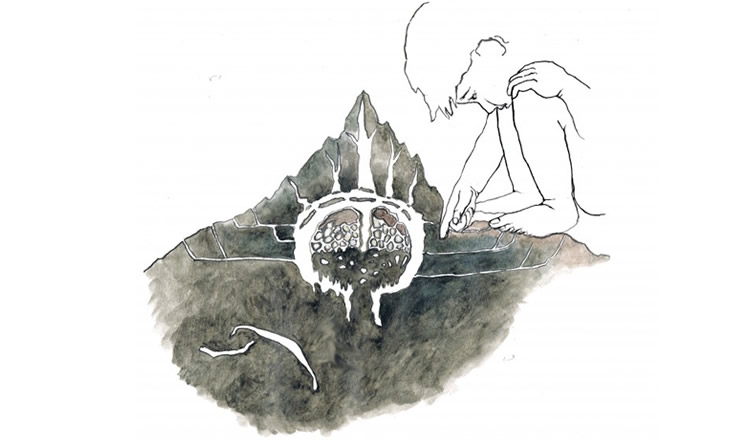

I shall begin, as Krakow began, with a cave. The cave and rock geology of Wawel Hill were formed, I believe, about 25 million years ago. My cave is at Pech Merle in the mid Pyrenees, in France. It was discovered in 1922: Miłosz was eleven. It is one of the caves where European art began, perhaps twenty-five thousand years ago in the era geologists call “Upper Palaeolithic”, around the time when Stone Age dwellers were leaving the first traces of human habitation in the cave in Wawel Hill. Art as we know it, began at Pech Merle, and other caves of the same era in galleries deep underground, when people painted spotted horses and woolly mammoths on a rock wall. Art begins, in fact, with representing nature. People call the Pech Merle cave, “an art gallery in a palace of nature”.

Miłosz’s imagination, too, was fired first and always by nature. Growing up in his rural landscapes he wanted to become an ornithologist. “I knew all the names for birds,” he told Paris Review in 1994. And the books which first entranced him, he said, were books on nature.

Just as his poems are mixed up with many things, so the beginnings of art are mixed up with the beginning of other things. First the beginning of science – that word which comes from scientia, knowledge. Both art and science begin with close observation – a wish to translate (or conjure or re-see and reflect upon) the nature we see. “Both scientist and artist,” Miłosz said, “have a desire to grasp the world,” and as a child, his hero was Linnaeus. “I loved the idea that he had invented a system for naming creatures, that he had captured nature that way. My wonder at nature was in large part a fascination with names and naming.” A later hero was Einstein: he wrote a poem to him. Poets often feel a common bond with scientists who look creatively, both passionately and dispassionately, into the “secrets of nature”.

The second thing which Pech Merle suggests is mixed up in the beginnings of art, is something with which all artists, all poets, struggle all the time: the question of “form” and its relation to reality. While we try to represent the reality we see, we also shape our experience of it – of a wild horse, for instance – but we distort while we represent. We can never do “accurate” entirely: we put ourselves in too. “Objective” always has that “trace” of the subjective.

Miłosz valued “realism”: poems which focus on “real things”. “What I seek in poetry,” he says in his essay ‘Against Incomprehensible Poetry’, “is a revelation of reality:” description, which “demands intense observation, so intense that the veil of everyday falls away and something we paid no attention to, is revealed as miraculous.” He called the poems in his anthology, The Book of Luminous Things, “loyal towards reality”.

How “loyal” are the horses of Pech Merle to the reality, the mammals, of Upper Palaeolithic France? Did such spotty horses really exist, or did the cave artists think they “looked better” with spots? Are they, in fact, dream horses, spirit horses, horses of the imagination?

Did such spotty horses really exist?

Did such spotty horses really exist?

Cave-art experts and Palaeolithic zoologists have argued both cases. The horses, like the mammoths, are very life-like, in shape. But what about the surface – the spots? My mother is 95 and a zoologist; and Darwin’s great grand-daughter. She told me last weekend, to my surprise, that she had seen Pech Merle cave. “And I didn’t believe the spots,” she said. “Not at all!”

My mother – and the palaeolithic zoologists I have consulted – have not been recently to Market square in Krakow. My first evening here, I saw four spotty horses marked exactly like the ones at Pech Merle but I suspect this is a case of nature imitating art: that human selective breeding, rather than Palaeolithic evolution, shaped this particular reality.

Selective breeding rather than Palaeolithic evolution…

Selective breeding rather than Palaeolithic evolution…

Whether these spots are imaginary or not, the artist has closely observed the wild horses, and they remind us that when we represent reality, we also choose the form in which we represent. However loyal we are to reality, there are things inside us, as well as outside in the world, which influence the forms we choose. We are influenced by the physical and historical context, the outside environment: the real horses we see; and also the available medium, the pigment, brush and “canvas”. Experts say these cave-artists carefully used the shape of the rock wall to find the shape of the horse. But we are also influenced by what is inside us: inspiration, imagination, an aesthetic sense. Something inside makes us decide – spots, or no spots? Outline or space? How thick shall I do the outline?

A poet makes such decisions all the time. They are formal but also tonal decisions: the angle, the way you present and tilt that “real thing”. Those decisions never stop. You have to make new ones in each poem, each line.

After science, and form, the third thing which Pech Merle suggests is mixed up in art, in representing nature, is human self-awareness. In his Paris Review interview, Miłosz says that poetry is “an exploration of man’s place in the cosmos”

This is true of all art, and at Pech Merle it is expressed by what you see around the horse: human handprints. Someone spread their palms and fingers on the rock and blew liquid colour around them with a blow-pipe.

Someone spread their palm and fingers on the rock

Someone spread their palm and fingers on the rock

In his book The Road-Side Dog (1998), Miłosz mentions other rock-art cave-art handprints, made five thousand years ago in a cave around Big Sur by Esselen Indians. His prose poem there, The Edge of the Continent, speaks to his sense of how unhistorical the Californian landscape around them looks to a European eye.

“A savage landscape of mountain slopes steeply descending to the Pacific: canyons, narrow creeks carved into precipitous shores. Herds of sea lions stretch on rocks. In this desolation, it is hard not to think what came before. We are prompted by a habit of imagination that looks everywhere for remnants of castles, cities, lost civilizations. Yet here there is nothing, there has never been anything except this space, this ocean. With one exception, so curious it prompted Robinson Jeffers to write a poem on it.”

He quotes Robinson Jeffers’ poem:

Inside a cave in a narrow canyon near Tassajara The vault of rock is painted with hands, A multitude of hands in the twilight, a cloud of men’s palms, no more, No other picture.

In the Californian cave, those hands are the only traces of humanity. In Pech Merle, the hands were printed around the first art. (What would Miłosz have made of them? I wish we had a poem on that) They suggest that art begins not only by representing nature, but with marking human engagement with it: by mixing the trace of human presence into that representation. Art, nature, and “us-in-the-cosmos” belong together. The hand we use to explore the cosmos, represent nature, grasp, touch and communicate – to wave – is itself “part of the picture.” But along with that visible hand is something more: the invisible trace of human breath, because the colour round those hands was put there by a blowpipe.

Poetry depends on breath in two ways. For inflow, in-spiration, the air we take in from the world: everything we invoke by the Latin word spiritus, spirit. But also for ex-pression, when a poem brings out what we have inside us. Words, and music, whose presence in the world is voice.

A hand which reaches, grasps and writes, is the visible token of our powers of communication and its invisible counterpart is voice. What we make with hand and breath, hand and voice is a picture of nature which includes both our experience of it and our expression of that experience. The “real” spotted horse is not just the horse but also our inward grasp of it, and our communication to others, of what that horse, and our understanding of it, might mean.

I’d like to read our first poem, Artificer in this light. Its historical context, the shape, as it were, of the cave wall, is Poland in 1933 when Miłosz was a member of the Catastrophists, avant garde writers who looked at the future – rightly – with an apprehension of doom. In later years Miłosz would have been content to forget his poems from that time but he was persuaded to include a translation of this one in his 1998 Collected Poems. It is not in his 2006 Selected and Last Poems and a 2001 footnote suggests why. “Angry reaction to the inhumanity of our times,” he says, “has seldom found expression in texts of lasting artistic merit, even if some of my poems stand as testimony.” So I guess – though there are people here who will know much better than I – he may not have been completely happy with the tone of this. It has a flavour of rhetoric, which Yeats says comes out of our quarrel with other people whereas true poetry comes out of the quarrel with ourselves.

It is an angry poem. Art-ificer means “maker of art” but this is ironic: it is a portrait of a destroyer. Hitler and Stalin are within him. He cuts the glowing walls in two,/ breaks the walls into motley halves,/ looks at the honey seeping from those huge honeycombs. This destruction is the only landscape able to make him feel – and he plants a big load of dynamite.

I’d like to look at the way it speaks through concrete images to present a consciousness “exploring the cosmos.” The artificer looks at honey seeping from the houses. He wonders. He observes: the clouds and what is hanging in them. It is a portrait of looking: looking at real things getting broken.

In 1912, the year after Miłosz was born, Ezra Pound’s modernist Manifesto told poets to be precise, to focus on the concrete thing. “Consider the way of the scientist,” he said. “Go in fear of abstractions. The natural object is always the adequate symbol.” Here, in 1933, is Miłosz putting that into practice. What hangs in the clouds? Globes, penal codes, dead cats floating on their backs, locomotives./They turn in the skeins of white clouds like trash in a puddle. As he says in his Luminous Things Introduction, “poetry deals with the singular, not the general.” He conveys the horror and scale of destruction through individual concrete images, accurately described. But we see the hand of self-awareness too, in the personal address: “Sharp knuckles shine that way, my friends.” As soon as we hear that, we know we are invited to look with the poet in a particular way, at this human consciousness looking at the cosmos.

II

Jump ten years to the next poem, and another consciousness observing destruction. But now it is the poet looking, and catastrophe has come true. The Nazis are in Warsaw. What can the horses and hands of Pech Merle say about this awe-inspiring poem, one of the first poems about the holocaust: A Poor Christian Looks at the Ghetto?

As in Artificer, we have concrete things. The tragedy and horror, the tone of moral responsibility, the burrowing for the roots of destruction and cruelty, come in obliquely at first, through a mix of the surreal with the earthily real. Its control is almost despairingly perfect. Form, in fact, calms you down. “After great pain, a formal feeling comes” says Emily Dickinson and Miłosz talks in an essay about “the positioning of the voice, when one wants to howl but screeching is inappropriate.” Part of the form and technique of this poem is the “positioning” of its voice.

It begins with nature (Bees build around red liver, ants build around black bone) and evokes destruction through incantatory repeated images which mix social insects with a litany of concrete human objects broken and torn. But it includes the subjective “hand” of self-awareness. I am afraid, I am terribly afraid of the guardian mole. What will I tell him? At the end, I becomes me, subject becomes object: He will count me among the helpers of death.

As in Artificer, Miłosz uses the image of raided honey for a community split apart: bees build around the honeycomb of lungs – the source of breath, of life. The horror is represented through concrete images and the focus – what to represent – is achieved through control of how to say it.

One aspect of this control is the “self-discipline” which Miłosz discussed in an essay called Who Was I? Self-discipline is a double edged sword. “Those who lack it, yearn for it. Those who have it to spare, know how much is lost through it, and long to be released from it, to proceed through the hand’s own free momentum.” That free momentum is what all poets long for and rarely feel they have. (Perhaps it is an important dream to feel you don’t have it.) “To gain that freedom,” he says “is to commune with a reader, hoping for some flicker of understanding in the eyes, that we are joined by the same belief or at least by the same hope.”

Here is where the “contradictions” come in. In an essay on T S Eliot, he says the tension which a poem needs “derives from contradictions”. He sees contradictions in himself; he values them in poetry. Form brings up the most vital contradiction if all. You want the control, but you also want to break free of it. You want the freedom; but you also, simultaneously, want the boundaries of formal convention. Form can give you freedom, but freedom also lies in escaping form. “To obey the freely moving hand,” he says. “Is that possible?”

He reminds us that questions of formal freedom are bound up with art’s role as communication. How you say something is, yes, inseparable from what you say, but also from whom you are saying it to. The angle you take to the universe, the beam of light you throw on “the real thing”, affects the other as well as yourself. “I write for an ideal person who is a kind of alter ego,” he said. “I don’t care about being more accessible. I assess whether my poems have what is necessary. I follow my need for rhythm and order, and my struggle against chaos and nothingness, to translate as many aspects of reality as possible, into a form.”

The spots on the spotty horse loom up at us here, but we should remember there are also political correlatives. Formal freedom is interdependent with social freedom. The classic book he wrote in Paris in 1953, “under great inner conflict,” as he said, after he received political asylum and broke ”free”, of Soviet ideology, was The Captive Mind. But before that, in the Forties, the Nazi years, he found formal freedom in two ways. “I was uneasy as a poet,” he said about this period. “I had come to understand that poetry could not depict the world as it was—the formal conventions were wrong. So I searched for something different.”

One solution was the long work, “The World (A Naive Poem),” consisting of short poems which he compared to William Blake’s “Songs of Innocence.” “I considered the world so horrible that these childish poems were answers—the world as it should be, not as it was. In view of what was happening, “The World” was a profoundly ironic poem, a search for the grace of innocence.”

The other solution was his cycle “Voices of Poor People,” trying to find “a way to deal directly with the Nazi occupation.” He was reading Chinese poetry, looking for “clear images and strong colours that I could inject into a dark, black and red world of the Nazi occupation.”

Afterwards, he described his poetic development as shedding skins, “abandoning old forms and assumptions.” “My poetry is always a search for a more spacious form.” But that search had to be undertaken under contradictory demands. The freedom to say something newly, which comes from observing formal constraint (like the ironically childish poems), versus the yearning to fling out and do things more openly. “Literature is born out of a desire to be truthful,” he said. “Not to hide, not to present oneself as somebody else. Yet when you write there are certain obligations, what I call laws of form. You cannot tell everything. Poetry imposes certain restraints. Nevertheless, there is always the feeling that you didn’t unveil yourself enough. A book is finished and appears and I feel, Well, next time I will unveil myself. And when the next book appears, I have the same feeling.”

III

Looking at a third poem, Meaning, I want to keep thinking about his word real while putting formal freedoms beside some other freedoms. One is the freedom of nature, movement in space and landscape – like that sylvan landscape he enjoyed as a boy, through which he escaped in 1940, and to which he returned in 1989.

Another is ideological freedom. He said he wrote The Captive Mind to “free himself” from “the demon of the 20th century”: belief in historical necessity, that it all had to happen like that: that history develops along preordained lines. But thirdly there is the political and social freedom he won through his own journey of escape, from Vilnius to Warsaw, to Paris and finally California – where in 1969 he wrote the poem “To Raja Rao,” in English: perhaps because it was written to an Indian writer.

But writing in another language itself explores new freedoms and new limits. That poem describes his geographical journey in terms of a quest for “real presence”, a concept which derives ultimately from Plato’s Theory of Forms. Plato distinguished the reality which we perceive with our senses, from a super-sensible world of Forms which are made by a god. We see a bed: a bed made by a carpenter. But it derives its meaning from the Form of bed, the “real” bed, which is made by a god who wished to be the “maker of what is real and true.”

Just as the divinely made Form of the bed lies behind the carpenter’s bed, so this Platonic idea lies behind the concept of “real presence” in Catholic theology, where it refers to the mystery of the immanent, the divine inside the thing. And in To Raja Rao, Miłosz describes how he moved on, from tyranny (Soviet Warsaw) to the republic of Paris and finally the great and moderately corrupt republic of USA. Addressing an Asian poet, he is conscious of California on the edge of a continent, facing Asia. So far, he says, he has felt on his journey that

A city, trees, human voices lacked the quality of presence. I would live by the hope of moving on. Somewhere else there was a city of real presence, of real trees and voices and friendship and love.

Thirty years later, our poem Meaning picks up that sense that the real presence must lie somewhere else. Miłosz wrote it in 1991, two years after he had seen Krasnogruda again.

The “control” in it, and also the freedom, comes from the discipline of a convention: the ancient Greek “amoebaic” convention of question and answer.

In his poem “Ars Poetica?” he says the purpose of poetry is to remind us “how difficult it is to remain just one person” and his poetry is often called polyphonic. “I have always been full of voices speaking.” But this poem has only two voices, because there are two views at stake here, two possible “meanings”, two ways of looking at meaning.

The first voice, of the first stanza, claims that when he dies, he will see the world’s “true meaning” beyond the real things. But there is a wry laugh in this voice, as if he is mocking himself for this hope. You see it in the capital letter to Up. What never added up will add Up. This is his “romantic irony” which he said was integral to his writing: “One participates and observes at the same time. Falling down the stairs, one sees it as funny.”

When you read aloud the tragic fifth poem, Orpheus and Eurydice, you see that same wry smile reflected on the audience’s faces when they hear the lines at the end of the second stanza:

Lyric poets usually have, as he knew, cold hearts. It is like a medical condition.

But in Meaning, the voice of the second stanza picks up that irony to challenge the first voice:

And if there is no lining to the world? If the thrush on the branch is not a sign, But just a thrush on a branch?

The third stanza replies, insisting on believing in meaning. Even if there is no lining, and anyway we know the lips will perish, what those lips say still exists. The word – meaning, the hand in the cave – goes on communicating:

a tireless messenger who runs and runs through interstellar fields, through the revolving galaxies

Miłosz did not warm to poets who focussed only “on their inner life.” “I didn’t want,” he said, “to write purely personal perceptions.” He saw himself as a hunter of meaning, “who grieves because reality cannot be captured.” He wants to capture the meaning, the truly “real”; even though meaning is not only within the real thing but beyond it, and therefore uncapturable.

This sheds light on his Introduction to A Book of Luminous Things, and the value he placed there on being “loyal to reality.” There is something in real things which is more than simply what we see. He quotes Cézanne: “Nature is not on the surface: it is inside. Colours, on the surface, show that inside.”

In terms of Pech Merle, the spotty horse is real but is also a spirit horse, a horse inside and beyond the real one: a “real presence”. The “meaning” of the horse is more than the horse we see. It is made by breath and spirit as well as hand. “I believe,” Miłosz tells Paris Review, “the world we know is the skin of a deeper reality – and that reality is there. It cannot be reduced to mere words.” Real, to him, is both visible and invisible. Both hand and breath.

IV

This belief is explicit in the 4th poem, Presence. The form here is quite different. Freer, perhaps. No stanzas, no separate voices: instead, a separation of lines, as if the atoms that hold the poem together are fluid. The lines float on their own. But in sequence (like the running child with which it begins) they create a clear movement of thought through the poem.

The first 5 lines move from the running child to the child’s sense of a Presence, which held him close. In the second 5, this Presence speaks to him through the sounds of nature. Then we get the distancing of hindsight, and of the conditional. “If” I had been brought up pagan,

I would easily have known the faces of the gods.

But I grew up in a Catholic family, so my surroundings were soon teeing with devils

These lines continue the argument of his 1969 poem To Raja Rao. In that poem, he says he escaped tyranny (of a Soviet system), but cannot escape his Catholic upbringing and its guilt:

I hear you saying that liberation is possible … No, Raja, I must start from what I am. I am those monsters which visit my dreams and reveal to me my hidden essence.

Presence goes beyond that Catholic boundedness. Its sense of immanence, of real presence, goes beyond the divide of pagan versus Christian. “In truth”, he says he felt as a boy in nature, all possibilities of divine meaning and presences:

I felt their Presence, all of them, gods and demons As if rising within one enormous unknowable Being.

Miłosz invokes what he called the “platonic dualism of soul and body,” through his “romantic irony”. Maybe the core of the value he puts on contradiction lies in the two ways of looking, both objective and subjective. He has the clarity and distance of a historian and philosopher, but also in this poem the openness of the mystic – without barrier, barefoot – and the personal breath, the yearning for that “flicker of understanding,” the communicative power of lyric.

Put in concrete terms, this is his tension between distance and closeness. “The secret of all art is distance” he says in Luminous Things. “I feel things of this world should be contemplated rather than dissected—a detached attitude towards objects, like Dutch still life. In his essay On Exile, he said, “A loss of harmony with surrounding space, the inability to feel at home in the world, so oppressive to a refugee, paradoxically integrates him in contemporary society. It makes him, if he is an artist, understood by all. To express the existential situation of modern man, one must live in exile of some sort.” Art, he says, should “stand outside the turning wheel, approach an object without passion, without desire. A good definition of art is detached contemplation.”

The way he opens A Poor Christian seems to use that “medical condition” of a cold heart: the heart which can suddenly go cold for a moment in the congealing chill of “form”: the “splinter of ice” which Graham Greene claimed existed in the heart of every writer. He seems to take a step back, start his “look” at the burning ghetto from an unexpected distance. In fact, of course, it is not ice at all, but fire: for lyric poetry needs closeness too: the hand of the personal, the truth of saying I, and relating to you I ran barefoot, I grew up, I felt. And what he feels is held close.

V

The hand of the personal is what we get, supremely, in Poem 5, Orpheus and Eurydice, which is for me one of the most perfect and profound poems in any language, any era.

Again, we start with the objective, with grainy “reality”. Outside Hades – fog, tossing leaves, car headlights. Inside, corridors, cold and electronic dogs. Plus subjective feelings: uncertainty, humanizing, the when he was with her he thought differently about himself – and the guilt. And again, there are two ways of looking, distanced and close. “He” is Orpheus the mythic poet but also the real poet who has lost his wife. Both enter the earth, the cave of Hades.

For his defence, he has the lyre, the visible sign of his voice, his “music of the earth” – that is, of intense enjoyment in the realities of this world. The passage beginning, He sang the brightness of mornings, is something I go back to again and again. It comes over as Miłosz’s own credo, culminating in what he feels he has achieved as a poet:

having composed his words always against death having made no rhyme in praise of nothingness.

Can we leave him singing in Hades a moment, and go back to that other underground, the cave of Pech Merle? In France, those hands came to be called, ‘’Les Mains Négatives’ – negative hands, absent hands. This became the title of a short 1979 film by the French writer Marguerite Duras. The film is a sequence of images: Paris boulevards early in the morning. Advertisments, shop signs, banks – and street cleaners, Africans, Moroccans, Portuguese femmes de ménage. Poor immigrants who clean the city before dawn and then withdraw, leaving the city to those of us who work and play there in the day. Duras herself speaks the voice-over text. She imagines the man who made the negative hands in a pre-historic cave, entering the cave alone, crying out in the solitude to you: ‘tu’, ‘toi. She turns the “negative hand” into an appeal for communication.

Her film is social and political. It suggests we modern city dwellers are as disconnected from the ‘negative hands’ of prehistoric cave artists as we are (by class division) from immigrant workers who also, before dawn in a modern city, leave a “negative hand.” The only trace they leave of themselves is an absence: they leave it by wiping away marks on surfaces of the city. Maybe, the film suggests, we should use these handprints from pre-historic men and women, to remember other men and women we come into contact with but do not see.

Poets, however, hearing that phrase “negative hand,” can’t help thinking of that other “negative” power which John Keats identified: negative capability, the artist’s capacity to be open to the world and its marvels, to go beyond, transcend anything predetermined.

In the Republic, Plato compares us, in our relation to “real” things of this world, to prisoners chained in a cave. They see shadows, projected on a blank wall by things passing in front of a fire, behind them. They take those shadows for reality. The only person who really sees reality is the philosopher, who comes out of the cave and sees the true Forms, of which the shadows are mere simulacra. I think Miłosz – like Keats – felt that poetry also saw true reality. He valued supremely the physical things we see. It wasn’t just a respect for modernism and Ezra Pound – it was part of his faith. “My Catholic upbringing,” he said, “instilled in me a respect for all things visible.”

But he also valued what they ‘meant’. The “lining” of the world, as he called it in the poem Meaning: the immanent Presence within them, the deeper reality to which “the world we know,” is, or may be, only “a skin”.“I am composed of contradictions,” he also said, “which is why poetry is a better form for me than philosophy.”

He also valued communication, that “flicker of understanding in the eyes.” The underworld where we left him, where Orpheus seeks his beloved, is also the earth where the guardian mole of A Poor Christian searched for the roots of human destructiveness, and yet, paradoxically, it is the cave of making, too. It is the place of imag-ination, where images are made: the darkness where the poet has to sing “against death”.

The end of this poem is a place of light beyond heartbreak. A luminous exit from underground sheds light on the things of this world, and one thing it shows us is what we have to confront – real loss:

Day was breaking. Shapes of rock loomed up Under the luminous eye of the exit from underground. It happened as he expected. He turned his head And behind him on the path was no one.

In Plato, the Sun provides the light by which the philosopher perceives true reality. Here, it is the first thing Orpheus sees. Sun. And sky. And in the sky white clouds. What is invisible and immanent in this landscape is indeed a negative hand – the absence of his beloved. It even has a voice: everything cried to him: Eurydice! Like the second voice in Meaning, which asks the apparently nihilist question, What if there is no lining?, Orpheus asks the question which no one can answer, anyway in words. How will I live without you, my consoling one?

As in Meaning, an answer does come back: “reality”. The reality which includes nature, and music, and communication. We have what we have, says the end of this poem. We have what has been communicated. We have meaning and words, the messenger that runs from you to me, poet to reader, and on through spinning galaxies. We have the real horse, on the earth; and also the dream or spirit horse of the cave. Which contains within it our experience of nature, and what our representing of nature does: it turns us, as it turned our cave-ancestors, into pattern-makers, communication-seekers, artists. We have the hand and breath of art.

What this hand and voice of art offers is “music of the earth” – the earth that contains everything. Its darkness is the cave of Hades and the grave, but also of imagination, creation and growth. It gives us the life of the senses, fragrance and sounds, herbs and bees. And its light, the sun, Plato’s Sun, which reveals true knowledge of true things, and does more than reveal now: it warms. We turn to and trust it in sorrow, and rest on it in sleep:

There was a fragrant scent of herbs, the low humming of bees, And he fell asleep with his cheek on the sun-warmed earth.

The bees, which in poems of 1933 and 1943, built their sweet but vulnerable and seeping honeycomb of community, and built around the lungs of breath and spirit, are now a source of consolation and another music, a low humming. So the poem ends with what it sang of, and with what Czesław Miłosz also sang of: the visible, sensible world. The earth in which we find meaning through the act of sharing, and through the hand of art.

Ruth Padel will read at Poetry And…Connection on 25 November