Mark Valentine

In 1958 a group of tutors and students at the University of North Staffordshire, Keele, published a booklet anthology entitled Universities’ Poetry One. It was a selection from submissions sent from undergraduates across the country. There were already several Oxford- and Cambridge-based poetry journals, some long-standing, but this was one of the first from any of the new universities: the Keele campus had been founded only nine years earlier.

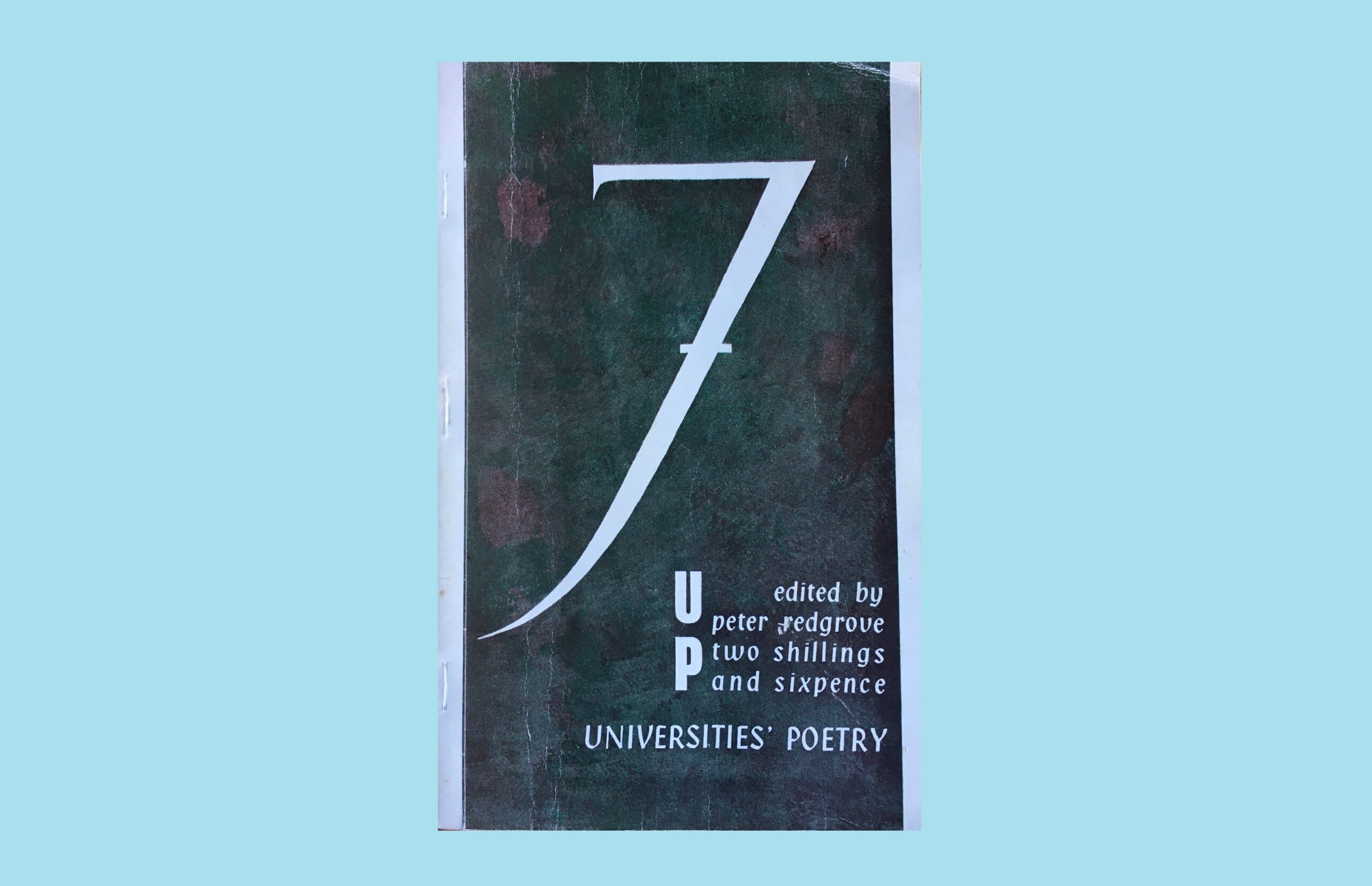

This became a series, organised by a joint universities’ committee, and there were seven issues of the anthology from 1958-65, and a ninth in 1970. Somewhere in between there was an issue 8; but most library holdings don’t have copies of 8 or 9. The copy of no 2 at King’s College London has the ownership signature of the avant-garde novelist B.S. Johnson, who was in it.

The first issue I chanced upon was no 7 and I got it at the enormous book barn at Temple Cloud, near Bristol (the name always suggests a type of Nepalese incense). Here all the books in the middle aisles were £1 each and the ‘vintage’, ostensibly more collectable, books around the edges were £4 each: customers are trusted to point out which is which at the till. The place has a café and, mysteriously, also sells Persian rugs.

‘Always check the pamphlets’ is one of my book collecting maxims, because you can sometimes find rare and strange things among them, and they are usually fairly cheap. It’s as if their ephemeral look and flimsy paper covers suggest that you can’t ask too much for them. There are some book collectors who don’t really like them because, since they have no spine, you can’t see them on the shelves and are always losing them. I keep mine in cardboard boxes from a tea company, which are just the right size. It also means that when I have another look at them they are delicately flavoured with Darjeeling, Earl Grey or smoky Lapsang.

Except with specialists, poetry pamphlets in particular are also often priced reasonably because ‘nobody reads poetry do they’ and even if they do they want the well-known names or recent idols, not some obscurity. Whereas what I want is precisely the obscurity. So it is a cheering business burrowing among the poetry pamphlets because even if I buy a handful or a dozen there will still be some funds left over for a coffee and a cardamom cake (for choice), if not for a magic carpet.

You have to work hard and fast when browsing at the book barn because there are so many books that if you stop to think you are lost. So I put the copy of Universities’ Poetry 7 on my pile and didn’t look at it until later. This issue, from 1965, and priced two shillings and sixpence, proved to be edited by Peter Redgrove, who was then thirty-three years old and the author of three books of poetry.

In a characteristic flight in his introduction, he notes that he was struck by how many poems he received were of a type not much seen in recent times: “the terrific-strange (apocalyptic fantasy and Dance of Death); humorous-terrific (useful surrealism); inanimate pastoral (in which the calm being of objects comments on the turmoil of humanity), with the closely-related beast-allegories and insect-dramas . . .” There was also much ribaldry and bawdy, and a welcome disregard for respectability. He had received 1030 poems from 256 authors, and selected 41 from 29. I make that a roughly 4% chance of getting in, which is about what you can still expect from the better poetry journals today.

I was particularly pleased to get the booklet because it included a poem by Sally Purcell, here as ‘Sally N. J. Purcell’, and ‘Totentanz’ must have been one of her first appearances outside Oxford. She was the first pupil from her state comprehensive school at Bromsgrove to get into Oxford, and had been encouraged by her English teacher, David Rudkin, now best known as the author of the strange and brooding television play Penda’s Fen (1974). She continued living in Oxford after graduating, working as a barmaid, typist, cataloguer and proof-reader, while she wrote or, as she put it, ‘uttered’ poems. These are brief mystical vignettes often about Arthurian knights, alchemists, pagan demi-gods; like distillations of David Jones, Charles Williams or Kathleen Raine, not fashionable then or now. But they are beautiful, concentrated, haunting, and induce reverie, or so I find. The poem here is about a windy night, where the storm is described as ‘growling like Grendel’ and a traveller is seen in ‘scarecrow rags’ under a ‘cracked moon’. Perhaps a tinge of de la Mare in there too, I should think.

But Sally Purcell was not by any means Peter Redgrove’s only good catch. The first two poems, both about a pregnant white pet cat, are by Angela Carter of Bristol University. There is never any shortage of poems about cats, as any editor will attest, so these must have stood out to snag the attention. And, being Carter, they certainly do. ‘My Cat in Her First Spring’ and ‘Life-Affirming Poem About Small Pregnant White Cat’ achieve the difficult feat of being both snug and strange, and, in a series of offbeat images, convey boldly the wonder of gestation. The expectant feline is a ‘melting snow-cat haphazardly thrown together/by careless children . . .’

A few pages on from Angela Carter we encounter ‘Cockling’ by Iain Sinclair of Trinity College, Dublin, the now noted author and psycho-geographer. He and a girlfriend gather the ‘knuckles of shell’, while ‘She held up her orange skirt/and drove her strong fingers/into the mudsand.’ It doesn’t end in coition—‘we lay half the town apart’—or a feast: ‘Inside all was green and/quite inedible’. The resigned and melancholy tone rather reminded me of Philip Larkin. Ten years later Sinclair was to publish Lud Heat, the book of apocalyptic London poems that became a cult object.

Meanwhile, D. M. Black of Edinburgh, then 23, was to share a Penguin Modern Poets volume with Redgrove, and with D.M. Thomas just two years later in 1967. His piece, ‘Major Iglu Explains His Beard’ is one of the more original and wayward pieces, about an eccentric sea-dog in the Indies, with a bit of a hint of Spike Milligan or Viv Stanshall about it. Another Edinburgh contributor who made it into the Penguin Modern Poets series was Alan Jackson, who was in no 12 (1968) with Jeff Nuttall and William Wantling. Redgrove chose two short sardonic anti-establishment squibs, agreeably brusque.

Yann Lovelock of Sheffield also went on to become widely-published. His first piece here is a bleak description of Clifton in Connemara, and the other, ‘Fat Man’, a picture of a downtrodden individual. They are both highly painterly, landscape and portrait, with adroit observation (‘ . . . nailmoons of villages/Slim as the catch/And poor as seaweed/The railhead abandoned, sodden and westernmost.’) I liked the image of the fat man’s daughters, ‘. . . svelte/As violins and sinuous/As saxophones’, the way the sibilance suggests the shapes.

There’s a ‘Lady With Cello’ in a portrait from Stephen Mulrine of Glasgow, who also offers one of a backstreet ‘Diogenes’: both of these are character studies that almost match the keen-eyed gaze of an Elizabeth Taylor novel. This poet was included two years later in Poems by Alan Hayton, Stephen Mulrine, Colin Kirkwood, Robert Tait, Four Glasgow University Poets, introduced by Edwin Morgan (Akros, 1967) and went on to become a translator of Strindberg, Ibsen and others.

Jenni Calder of London University was one of only three to have three poems selected, two of them about horses, one at a blacksmith’s, one owned by a sheik. They seem to show a keen eye for horse-flesh and perhaps for human. Her then husband Angus Calder of Sussex also had three in, two about food: one on berries, one on bread and cheese; well-observed still lives. The third, about how his lover becomes a stranger (partly because he’s too busy ‘scowling over a poem’ in the bedroom), is also in its way a still life. Both became noted historians and arts administrators if not pre-eminently poets.

So there are quite a few here who stuck with the craft and became known for it, and for other literary achievements. But not all stayed in the public gaze. The other poet with three pieces, apart from the Calders, was Jean Symons of London. Her pieces (‘The Long Art’, ‘Author’, ‘Three Voices’) are odd, come at things from oblique angles, jumble words about a bit, out of the obvious order, catch how the mind works. I should guess the influence of Stevie Smith, whose Selected had come out 2 or 3 years before. If I had been looking without knowing what came next, I’d have said she was one to watch (I like to think I’d have seen Carter and Purcell too).

Symons was a winner of the Eric Gregory Award in 1964, with Robert Nye, Ken Smith and Ted Walker, all of whom went on to publish widely: she didn’t, at least not in book form. There is no volume of poems under the name Jean Symons in the library catalogues, but I did trace a twenty page chapbook, Hiding in Chips (2001) from the Pennycomequick Co-operative of Plymouth, which the bookseller, who wanted a pound for it, described as ‘unread’. (The peculiar name of the press comes from an area of Plymouth, up by the railway station.) Some of these poems had appeared in Ambit and Devon Life, which might be thought a rather odd duo.

Are there any more overt influences in the other poems here? Ted Hughes, certainly, in poems about a hooked fish and a game bird: R S Thomas, maybe, in one about a bowed ploughman. There’s nothing Betjamanesque (probably thought too vieux jeu) and, at the opposite end, nothing much Beat or Beatnik or Beatles. Pop music, then being broadcast by pirate radio stations, does not appear. In fact, sex ‘n’ drugs ‘n’ rock & roll are not much in evidence at all: and Last Exit to Brooklyn, Hubert Selby Jr’s cult book of the year before, when presumably the poems were mostly written, does not make its presence felt in any poems of the really mean streets.

The nearest is perhaps W.B. Oxley of Leeds who contributes ‘Swealing’, about slum children setting fire to an embankment and fanning the flames so they catch, then waiting to watch the fire engines come. It captures an adolescent tone and way of thinking unerringly, but stylistically (unlike Carter, who is spasmodic and exclamatory) it is solemnly mainstream, and thematically it belongs with the Angry Young Men of the Fifties.

In a couple of years The Lord of the Rings in paperback would sweep through campuses, and the flower people, whose own term for themselves, now largely lost, was ‘freaks’, would be introducing a second phase of the Neo-Romantic (there was an earlier one in the Fifties). The editor of the elusive no 8 must have been inundated with elves.

I am not sure I quite saw what the fervid and generous imagination of Peter Redgrove did in the student poetry of 1965, but instead I noticed something I didn’t expect. Most of the poets were interested in other people, or other creatures, in how things might be seen or experienced by them. That can be pretty ‘terrific-strange’ too.