Richie McCaffery

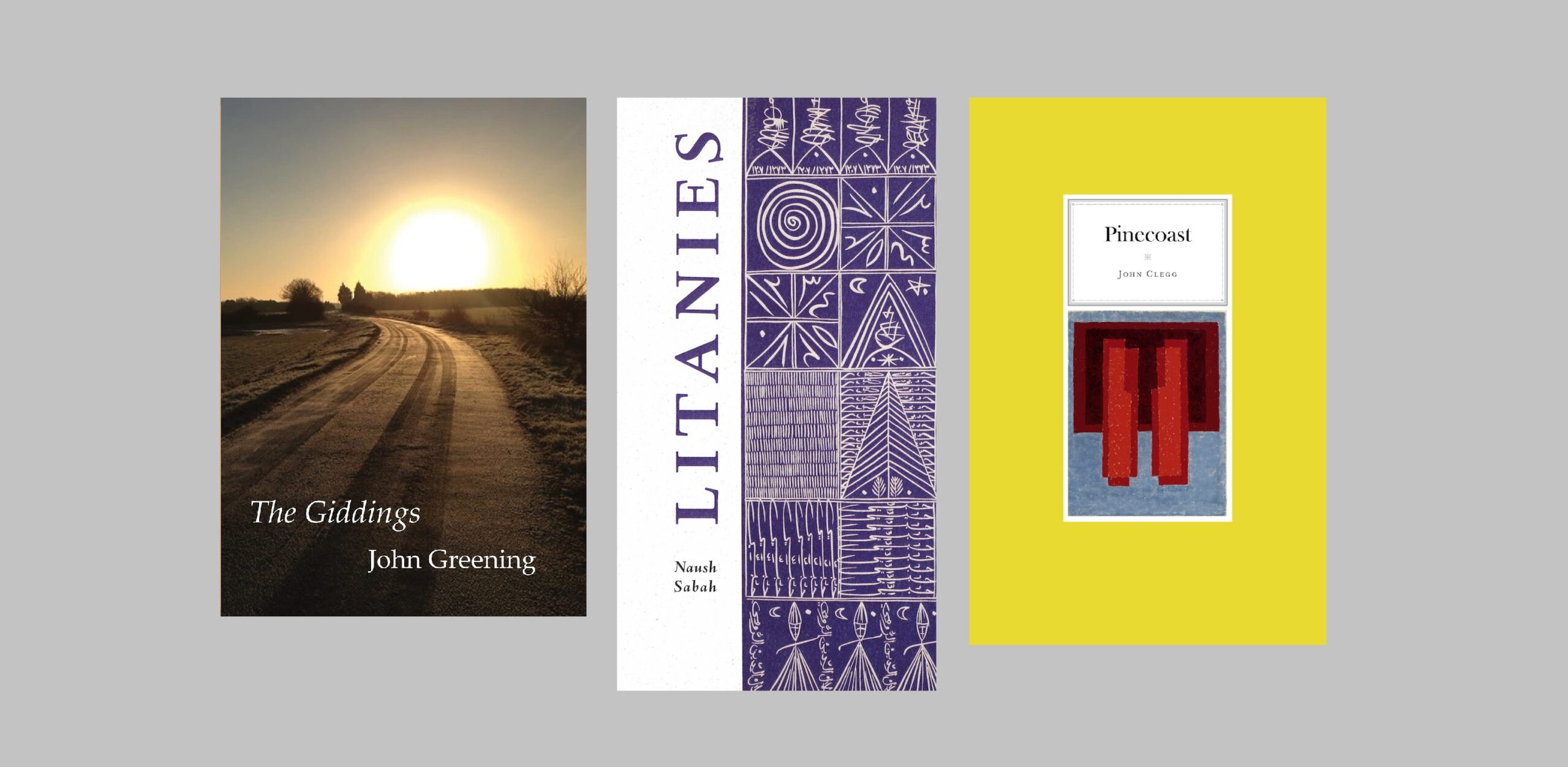

It is apt that John Greening recently edited the Carcanet selection of Iain Crichton Smith’s poems. There’s an anecdote that does the rounds in Scottish literary circles, probably apocryphal, which goes: Norman MacCaig was walking down the street in Edinburgh and he sees a friend, so he stops them and says ‘I’m desperately worried about Iain (Crichton Smith), he hasn’t published anything for days!’ I mention this because Greening himself is almost as prolific as Crichton Smith, with new pamphlets and collections appearing with dizzying alacrity. However, there’s no question of Greening spreading himself too thinly, as this new pamphlet, The Giddings (Mica Press, 2021), is further evidence of his range. It’s not merely a grouping of poems, but rather a picaresque and poetic account (part lyrical, part prose) of someone (a businessman) in the modern age getting lost in history as they follow a mysterious sign to ‘the Giddings’. The story becomes not a question of reaching a destination, but the sights and sounds and events along the way, with magical realist touches, such as the trees themselves breaking into verse. This is the voice of the English elm:

We could not make coffins enough for all of them, the religious zealots and atheists, the dancers and pontificators, all vanish from the landscape. As you will, with your over-eager business card made out of American pulp.

‘Everything is hosted, everything is vanishing’, as Alexander Hutchison once said so powerfully, and here the trees have witnessed generations of people and ways of life come and go, and have absorbed something of their spirit in their roots. Greening’s poem, too, condenses so many histories, that of Bishop Farrar, of the Civil War, the Plague and there’s an effective synergy formed between the trees and books themselves, being from the same source. Here is the weald of trees anthropomorphised as writers:

The field maple’s book of short stories is out though it’s only the big maples get the attention. […] The apple is co-writing (due from his small press) the pear’s rhyming slang cyclopedia. The book of the willow, the book of the cypress, are tear-jerkers. The larch does light verse.

The register of the poem-journey we go on is also winningly varied, from humour to profundity, such as the observation that ‘All things began with the squirrel and the jay’, that our countryside is made from the forgetfulness and industry of small animals and birds and we are only transitory players in it all:

Begin your walk back down the avenue, where civil war is hardly more than an unfurled leaf, a reign of peace this twig, where poet, thinker, cunning woman, sage are one extra inch around the waist, and the life of the oldest arboriculturist is just some rings, a little height and deeper roots. We never move. We make sure progress.

By getting lost, the unnamed protagonist actually begins to find himself in an ontological sense, and the journey becomes a one of enlightenment, almost zen-like, and his teachers are the voices of the trees, the poem ending with an antiphony between the yew and the birch. Here is what the wise old yew has to say:

Forwards and backwards are the same. He’s yet to realise that’s the case. Although he’s guessed it’s all a game of patience, not a human race.

Litanies (Guillemot Press, 2021), Naush Sabah’s first pamphlet, was perhaps one of the most acclaimed debuts of 2021. Sabah is well known as one half of the editorial crack team behind Poetry Birmingham Literary Journal. Easily the most visually prepossessing pamphlet of the three under discussion here, I found reading this a salutary experience, as a poet myself who strives for economy of expression, it is good to see poets using language for more sumptuous and lavish effects. The first poem’s title, ‘Litany of Dissolution’, gives you some idea of the heightened register being deployed here. The subject matter of these poems – apostasy, religious oppression, religious fear, the clash of the sacral and profane – are undeniably some of the biggest themes a poet can tackle and the language needs to be up to that task:

I abandoned the night prayers For sleep without ritual Ablutions in freshly clean sheets Masturbating without God watching for the first time

However, at times I feel some of the similes Sabah uses are bathetic to the purposes she intends, such as ‘hell dissolved like a nightmare’ (compare this to ‘hell dissolved like a mint’ on the next page which is quite original), while ‘desiccated death’ is surely something of a tautology. These are trivial snags, but they can undermine the force with which the speaker projects themselves off the page and into our heads. That said, I like how these poems take place in a post-theocratic realm, where ‘the deities have died but these columns endure’ (‘Of Monuments’), and the main thrust of argument to these poems is the possibility of replacing Sufi prayer with another type of incantation, that of poetry itself, ‘Ours is an oral tradition / and witness carries weight / like silence carries a howl’ (‘Litany of Desolation’). Sabah proves that poetry is more than capable of tackling issues of life and death in ways that prayer cannot, that it can somehow comment on religion from a higher vantage point, as if the poet has an omniscience all their own. Take, for instance, the remarkable chiasmus in the opening and closing lines to this stanza of ‘Of Mercy’ (perhaps the strongest poem in the collection):

if she lives they’ll praise God’s mercy the tubes protruding from her chest, yet our prayers tremble and dissipate over closed eyes and pallid skin still soft but cold in the open plastic box a coffin-like crib that houses a congregation of teddies holding constantly vigil my womb poor incubator still contracts now I wonder whether to blame myself but they’ll praise God for his mercy if she dies

Pinecoast (Hazel Press, 2021) by John Clegg is my introduction to Hazel Press, and while I feel £10 is rather steep for a pamphlet, they appear to make a very elegant job of it (I particularly like the little Thomas Bewick vignette on the back page). From the outset, I fell under the spell of these poems. If there was ever a prize for most striking opening line to a book of poems, I’m confident Clegg would win: ‘I helped a boneless ghost to cross a stile’ (‘Boneless’). The poem instantly puts us in a somehow whimsically surreal but eerie territory, the poem sparking more questions than it attempts to answer:

I thought he’d like it better on the other side. I thought to stumble on him early meant it was a favour that he wanted, helping over. Now I’d wish I’d left him thrashing at the bar, being worse luck where he is, met in tall pines. I wish instead I’d slackened my way home.

Perhaps this is the sort of poem Robert Frost might have written if he was on hallucinogens. The second poem ‘Arturumque atiam sub terries bella moventem’ is about writing a book about stumbling across a long lost draft by Milton and it reminds me of that cult documentary ‘The Cardinal and the Corpse’ (on YouTube, absolutely worth a watch) based on Iain Sinclair’s book of the same name, how non-existent books can still give birth to actual books. Clegg has a keen eye for the absurd, such as ‘Marduk’s giant idol’ being wheeled up a ziggurat in ‘Babylon’:

[…] they don’t know if they’re lulling him to sleep or if they’re terrified in case he goes to sleep. Those idiots, they’ve put their gods in pushchairs!

And again, in ‘RMS Empress of Ireland’:

In the shipwreck museum I look at the toilet seat which needed nineteen painstaking dives to bring to the surface

This poem goes further, rather like a dive itself, into the vanished old-world luxury of these enormous ocean liners with ‘fourteen / tanks of freshwater’ for poached eggs, bathing, highballs ‘at 3pm’ and ‘none / of those tanks breached / the night the ship went under’. Clegg has a knack for finding poetry and poems in unlikely places, such as lightning hitting the Celtic sea and the speaker remembering straightaway ‘what we married for’ (an epiphanic moment almost worthy of Hugh MacDiarmid’s ‘The Watergaw’, the speaker seeing a broken shaft of a rainbow and thinking of the ‘last wild look’ his father gave before his death). The deceptive simplicity of some of these poems is borne of great skill and confidence on the part of the poet. In ‘Quebec City’ the speaker stands (‘stone still’) in the ‘first stone house / on the American continent’ while his host shares around a tray of vol-au-vents:

And that was all which passed from wall to wall that day – although the grey American wind hauled its whole unrolled half hammered tarp across the roof, and gave a show of knowing full well how things went in stone.

It’s almost something of a magical feat to play out a poem in such a deadpan and lucid way and still reach a moment of elevated awareness and impact. There’s no need for that tired old back-handed compliment ‘shows promise’ about these poems, they’re the work of a seasoned professional and they make for highly enjoyable reading.