Holly Loveday

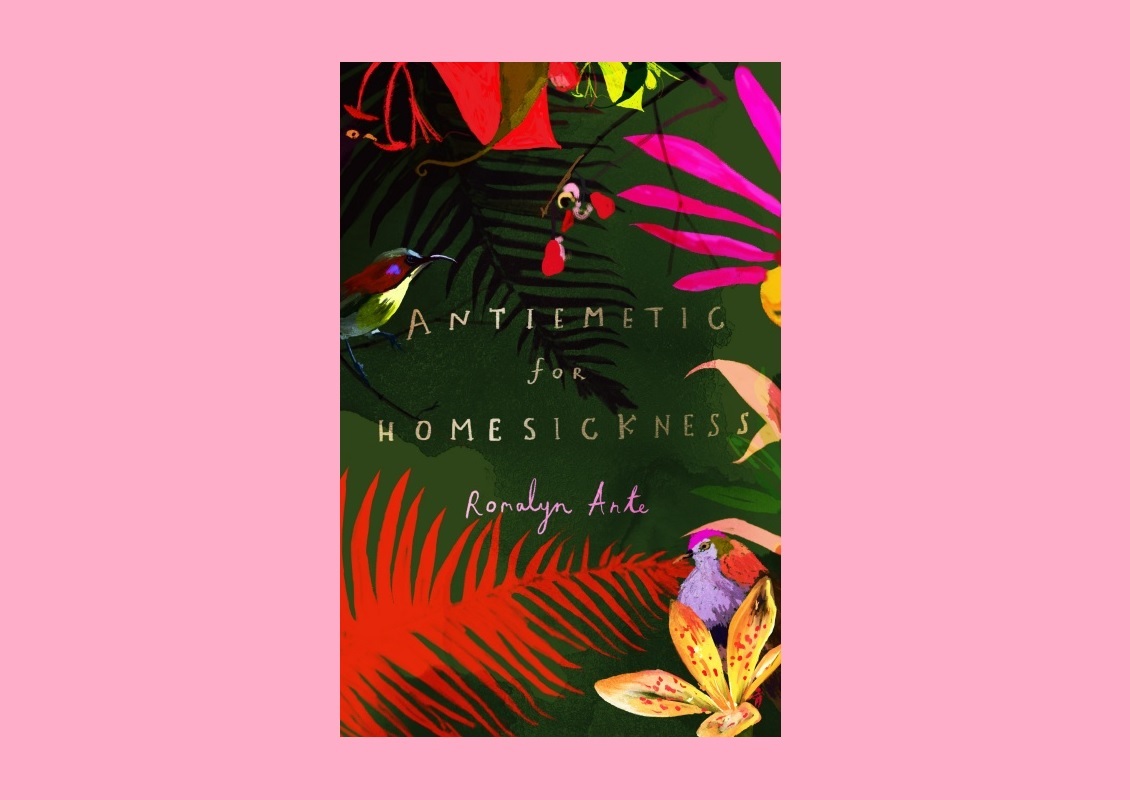

Romalyn Ante’s debut collection Antiemetic for Homesickness (Chatto & Windus, 2020) – flitting between clinical-white, squeaky hospital wards and the tropical abundance of the Philippines – allows us to experience what is it to be pulled in two directions. I write against a backdrop of Covid-19 forcing an entire world of separated loved ones, so Ante’s treatment of homesickness as a physical, emotional, and chronic diagnosis feels overwhelmingly apposite.

Ante writes with a voice that I can only imagine develops when the act of care is central to one’s life. She minces no words, nor does she adjust for, or exclude, the reader as she moves through English, Tagalog and Baybayin script in snapshots of time, place and voice. Yet alongside this is a dry playfulness apparent from the collection’s first page, where Ante matches the Duke of Edinburgh’s coarse treatment of the subject (“the Philippines must be half-empty; you’re all here running the NHS”) in ‘Half-Empty’: the Philippine diaspora that constitutes a large number of the underpaid, overworked NHS and private healthcare workers in the UK. Ante reminds us that Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) make up a third of NHS staff, and Ante herself remains a registered nurse and psychotherapist alongside her work as a poet.

Antiemetic for Homesickness strikes a balance between the devastating and the subtly comic throughout. The same romantic, vivid touch is applied to ‘the smoke of a Brummie accent on your face’ and the flavourful colours of the Philippine landscape, the ‘chandelier of jade vines’ and ‘haematoma of flowers’ (‘Tagay! [Drinking Lambanog with my Filipino Colleagues]’). Ante dives in further as she explores the ambivalence that accompanies homesickness: a longing for one’s former home while starting to develop feelings for the current one. The result is a lack of bloat to the poetic voice; accessibility, but also an unmistakable churning between love and grief.

Ante explores the many manifestations of care throughout the collection, addressing the implicit contradiction immigrant workers are faced with. Acts of care, such as nursing a patient, are non-reciprocal and invaluable. Yet a value is indeed placed on the care itself – a monetary wage – which is necessary for the vocation to continue. Ante speaks of those who ‘ceaselessly convert pounds to peso’ and send money back home – to care in turn for those left behind. She toys with the tension between sending money home as a form of sending care and its inherent isolation in ‘Mateo’, a poem in the obtuse shape of a Great British Pound. The theme of value, especially undervalue, comes to the forefront in ‘Invisible Women’ and the poem ‘[ ]’, where healthcare workers are a ‘snowball’ that ‘splatters/on someone’s chest’, ‘erased by sun rays’ in their passports and obscured by hospital sounds: ‘swish-snap’, ‘slap’, or the ‘bleepbleep’ of machines. Our nation’s embarrassing treatment of healthcare workers could not be more topical. These really are – to use the glib phrase – ‘essential workers’ who require a living wage, not empty gestures such as coordinated doorstep applause.

Antiemetic for Homesickness manages to stand so coherently as a collection on account of how the poems’ polyphony of voices interact with one another. The lyrical fracturing through a symbol in ‘Mateo’ is explored anew in ‘#family’. Again, Ante’s on-the-nose approach, using the medical shorthand (the # symbol) for a bone fracture to evoke its emotional counterpart, gains a subtlety through its directness. In contrast to the stop/start structure of ‘Mateo’, ‘#family’ flows between softer sounds. Its scattered sibilance ensures an easy movement through the second stanza with mothering hands that ‘soothe’, ‘swept’, and serve to ‘ease’ a ‘fissure’ in the speaker’s chest; an early diagnosis of homesickness following an exodus, one that infects multiple generations. The full rhyme of ‘leaves’ and ‘cleaves’ serves to maintain a stitched structure, the stability of family, over a revelation that momentarily cuts through the sense of security Ante constructs: ‘But I woke to the clatter of her luggage to find her gone’. Such a departure leaves the fissure permanently open. Here is the act of care compounded: Ante speaks of orthopaedics, of a mother caring for her child by staying but also by leaving, the child learning to care for themselves in their mother’s absence. The final image of the poem shows the speaker rubbing Vicks onto her own breastbone: an action that speaks to the cyclical nature of immigration, daughters forced to repeat their mother’s actions by leaving for the same reasons.

‘Repairing English’ and ‘Mastering English’ are further examples of dialogue in Antiemetic for Homesickness. This pair of poems, perhaps my favourite of the whole collection, employ enjambement with satisfying defiance and dexterity. In ‘Repairing English’ Ante takes the filler sound ‘like’ – formally termed a speech disfluency, a word to trip up and shutter the flow of sentences – and makes it the centrepiece of the poem. She drops likes at the beginning and end of lines, or a few beats before with a ‘likelihood’ or undercuts the expected fall of the line by closing with ‘lilies’ or feisty Nanay Lola, or ‘dialysis’. We are at the mercy of her retort to those who underestimate immigrant workers. As such, the unnamed ‘you’ which opens the poem sits ominously as both an individual and broader address. Ante’s comfortable use of couplets, a more traditional structure, is another point made and we are further teased in the poem following, ‘Mastering English’. Here Ante reworks the couplet form as a tick-box citizenship questionnaire, maintaining the enjambement created earlier. ‘A drop in the ocean’ can be just an idiom or ‘the migrants who mysteriously vanished at sea’. Ante creates options in a poem addressing a move across continents that many make with little choice.

This multiple-choice structure develops Ante’s investigation of visibility and the foreign tongue. She addresses the assumption that a non-Native English speaker understands less. As I touched on earlier, Ante’s skill with sound is a highlight in this terrain, where unfamiliar medical terminology and untranslated Tagalog are wound up together. In using interspersed Tagalog, often integrated into English sentences, Ante conveys her urge not to lose the worlds that are attached to these words. In ‘Patis’, Ante writes on generational shifts back home so that although ‘no one cooks patis anymore’, its richness is recreated in English. The onomatopoeic shape the mouth takes in reading lines like ‘certain sour-salt taste’ and ‘rich fish flesh’ are substitutes for the real thing.

This is a different kind of grief in separation: when things change in one’s absence. ‘Anagolay’, a prayer to the goddess of lost things, is a poignant confession to this feeling. It is a complicated and brave, emotional realisation, one that asks not for missed moments to return but to ‘let the misplaced objects recede’ – the act of letting go. It is to ask for the retrieval of lost will in those present, a hopeless patient perhaps, while ‘another world ebbs’. In essence, Anagolay is a poem about the pain of sacrifice, as an everyday experience, while still committing to it – as Ante reminds us: ‘the fifth vital sign has always been pain’.

The titular poem, ‘Antiemetic for Homesickness’, brings the collection to a close with an advisory and tender tone. We have moved from time as ‘a tattered blanket draped down your shoulders’ (‘To Die a Little’) that can only signify separation between loved ones, to a place where the snow of that foreign country can be ‘shawling you like a mother’s warmth’. The ambivalent core remains, however. Regressions into heartache are treated by imperatives to ‘keep’ memories, to ‘listen’ and ‘enjoy’ the music and food from home. The poem’s poignancy lies in its ambiguous recipient: does Ante remind herself of a remedy for self-soothing, or another OFW with the same story? Or are we privy to the transfer of advice from one generation to the next? In any case, the poem and the collection speak with care to homesickness the world over. Like all loss, it cannot disappear entirely, but it can become more tolerable with each passing day.