Kevin Gardner

According to the randomness of the laws of the universe, or at least of the postal service, I will occasionally receive by mail, in quick succession, review copies of poetry books that have very little in common with each other in terms of form and subject. My instinct is to treat them separately, but recently I have been drawn to a different reviewing experience. Although simultaneously reading vastly different poetry volumes can be disruptive and even alienating, the contrasts I expect to find can lead to unexpected connections. That has certainly proven to be the case with the books gathered here.

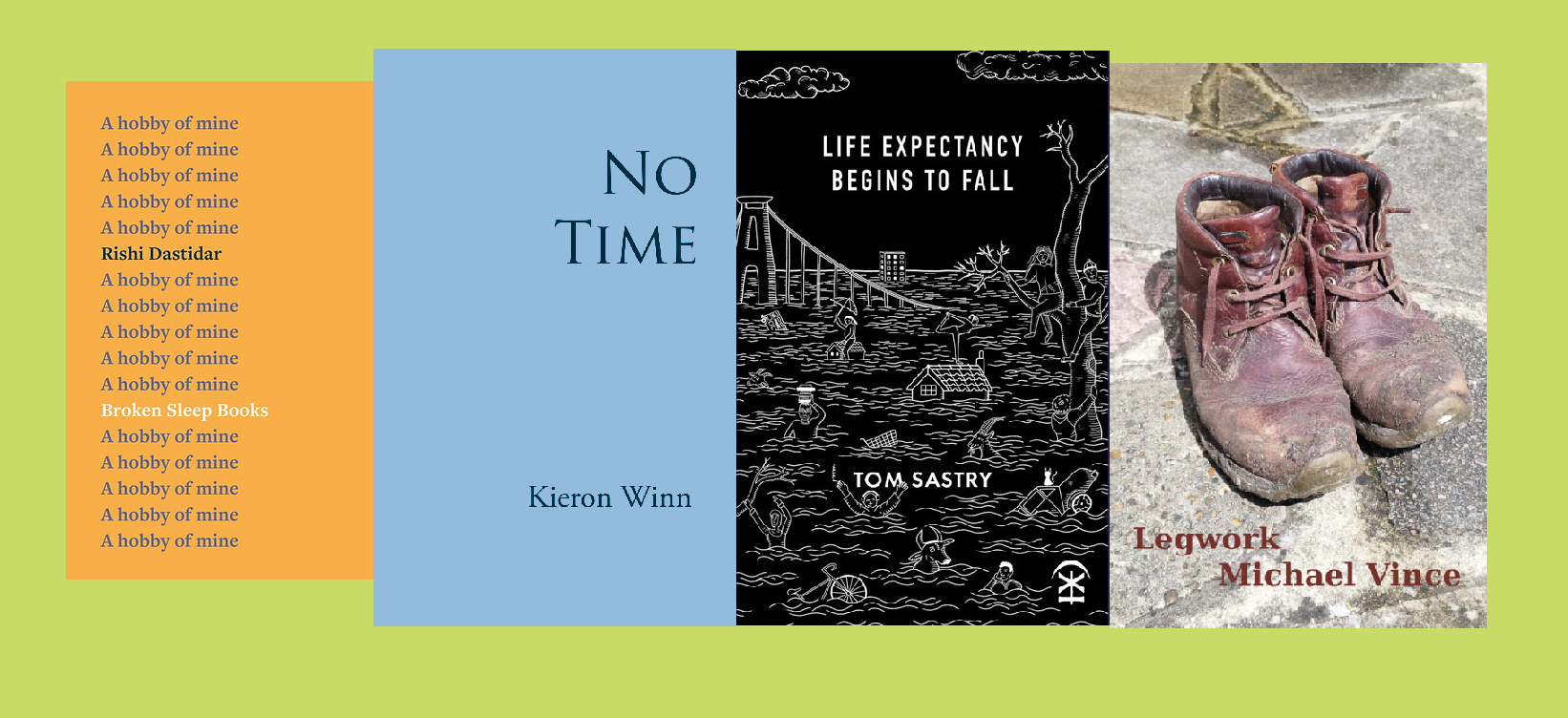

There’s an outlier, of course; there always is, otherwise the universe would not be random. While three of the books reviewed here are traditional, full-length poetry collections, Rishi Dastidar’s slim new volume, A hobby of mine (Broken Sleep Books, 2025) comprises more than forty-odd pages of witty observations, each beginning with the titular phrase. Individually, they are epigrammatic without being epigrams; taken together, they form what might well be the world’s longest anaphora. Never fear, there is none of the weightiness of biblical anaphora, nor need you expect to answer him with a litany for deliverance. Dastidar’s observations are the soul of wit; they are randomly organized, but categories emerge. You will find aphoristic observations:

A hobby of mine is performing life rather than living it.

A hobby of mine is mediating the world rather than experiencing it.

A hobby of mine is treading softly on your dreams.

A hobby of mine is instructing other people to take purity tests that I keep failing.

as well as the absurd:

A hobby of mine is bending light into a figure of eight.

A hobby of mine is match-fixing games of tiddlywinks I come across.

A hobby of mine is examining the past through a funhouse mirror.

A hobby of mine is training King Charles spaniels to be able to bark Martin Luther’s 95 theses.

Some are, naturally, autobiographical:

A hobby of mine is being crazy and south Asian but not rich.

A hobby of mine is waiting for the Philadelphia Phillies to swoon in September.

A hobby of mine is not going to parties, then wishing I’d gone.

A hobby of mine is wishing for temporary incapacitation that doesn’t actually change my life meaningfully.

A hobby of mine is railing against the inevitable and necessary oblivion of my writing, and by extension me, and my sense of self.

but most, concerned with the contemporary world, are pointed criticisms of daily life and our culture fragmented by insatiable consumerism and rampant political hypocrisy:

A hobby of mine is luxurious poverty.

A hobby of mine is waking up at 4.30 am with existential dread.

A hobby of mine is exaggerating slights into melodramas.

A hobby of mine is predicting when Miami sinks.

A hobby of mine is lowering the Atlantic.

A hobby of mine is thinking up sports entertainment formats for a post-apocalyptic planet.

Dastidar’s observations are a brilliant and mesmerizing catalogue of the absurdities and anxieties of contemporary existence. Think of the book as La Rochefoucauld’s maxims rendered with Martial’s wit. For the full effect, the sequence should be read all in one go, and the ironic effects will compound gradually. However, the book’s form will appeal to those who prefer to skip around randomly for choice gems, and if that is a hobby of yours, you will be rewarded as well.

A hobby of mine is trying to force unnatural transitions in order to link paragraphs of unlike subjects. Following the pattern established in his debut collection (The Mortal Man, 2015), most of the poems in Kieron Winn’s new collection, No Time (Howtown Press, 2025), look into the past – to the poet’s childhood and the lives and voices of ancestors, and to a Britain lost in the shadowy margins of time. ‘In a Boars Hill Graveyard’ (its epigraph: ‘After reading A Boars Hill Anthology’) expresses – in tidy Victorian-flavoured iambics, appropriately – that paradoxical sense that the past is simultaneously lost to us and still alive through language:

And though a mossy stone or lichened urn

Gives little sense that someone was alive,

A book has made the dead less taciturn.The book’s distinctive glimpse of life lived then,

That vigour, craft, extravagance and bliss,

Is nowhere in a cramped necropolis.

Much of Winn’s collection explores, in carefully crafted stanzas, this phenomenon of a Schrödinger’s past, both vividly alive and grievously gone, all at once. The book’s final poem comes then as a surprise. The Scuphamesque lines of ‘Voyager 1’ look into an endless future and an obliterated past. Launched in 1977, when it must have seemed to Winn ‘a homemade toy’ constructed of ‘Matchsticks, Meccano strips, and … kitchen foil’, the NASA spacecraft has since escaped the heliosphere and is now exploring interstellar space. Winn imagines Voyager 1 as our last voice, ‘the final artefact’ once there is nothing left of Earth, and no one left to speak, not even the dead in a Boars Hill cemetery: in that post-apocalyptic future ‘when Earth, ill-starred, / Cannot host life’. (“A hobby of mine is calling a year when our species disappears,” confesses Dastidar.) For a collection that tends toward the pastoral and elegiac, ‘Voyager 1’ comes as an unexpected but satisfying full-stop. It also forges unlikely connections with very different voices.

Reading Winn’s collection in conjunction with Tom Sastry’s Life expectancy begins to fall (Nine Arches Press, 2025) results in a surprisingly coherent polytonality. The poems in Life expectancy examine the personal and social effects of climate disaster, with the same disarming wit Sastry demonstrated in his debut, A Man’s House Catches Fire (2019); like Winn, Sastry presupposes the planet’s inexorable demise, but Sastry is less matter-of-fact in his dealing with doom. Recognizing that we have been facing the possible extinction of life since the atomic age, ‘A pre-loved film from the vintage shop at History’s End’ renders traditional notions of apocalypse as a nuclear disaster film on VHS, the images so clichéd as to be almost comical: ‘in a top-secret bunker / an old-school civil servant / reveals a tin of Continuity Rations’. But after the film ends, and despite its hokiness, new fears return: ‘The possibility of other disasters / survives with me,’ Sastry confesses; ‘Ice retreats, soil thins.’ The poem concludes with a placid acceptance of disaster’s inevitability and an escapist retreat into the transitory entertainments of re-used VHS tapes:

In the chapel of a perfect night

I can hear the world singthe song of its own ending

from the soundtrack to the movie of my life.I give each danger a year or two

then tape over the warnings.

It’s a magnificent ending: there’s the irony of the pastoral note, of course, but also the insistently personal focus which highlights that human self-centeredness is an essential ingredient in the ongoing climate disaster. That in turn reminds us how much easier it is to look away, to pretend it isn’t real or at least not urgent. (“A hobby of mine is carrying on as if there isn’t an ongoing apocalypse,” Dastidar records.) This is a recurring motif, returning with increasingly comic and satiric effects, for Sastry understands that satire often works best by way of a narrator oblivious to the horrors he describes:

In the country of what-you-don’t-know-can’t-hurt-you

our rivers are clear, our history true.If it’s too late to start cathedrals

or trust in a forty-year pension plan

too soon

to snatch the thing to hand

in the name of survivalI am glueing myself to the present

where water is drinkable and no bombs fall

blocking the artery of time.A distant inferno would enchant your night

if you saw it from the next coast.

So much torment is shut away, you might even be comforted

by a Hell with space for your friends.

This last extract is from ‘Everyone loves the end of the world’, an excoriation of disaster voyeurism. ‘We build great telescopes to watch stars die / send divers to explore drowned cities, give prizes / for pictures of flaming sinkholes / or bones bleaching by a dry lake,’ Sastry unsentimentally observes in lines that not only resonate with Kieron Winn’s ‘Voyager 1’ but also with a fascinating poem in Michael Vince’s latest collection, Legwork (Mica Press, 2024). Vince’s ‘Underland’ is meant to evoke Doggerland, a vast tract of Northern Europe that was inundated by glacial retreat several thousand years ago. Although the poem is primarily about prehistoric geologic forces at work eons before an arrogant humanity would develop the tools to intervene in planetary demise, the poem nonetheless alludes to our involvement today in melting icecaps and rising sea-levels, and our self-imposed obliviousness:

The drowned place, Underland,

it seeps slowly back to us

wherever we are, as the past

of plain, river, green hillock

long gone down, part of what

will cover us, whenever it is.

…

Bones, tools, dredge by trawl nets

from the land of sandbank and shoal,

future and past, mirror the silt

of the human world, dissolving

over and over, thinking, staring,

its features washed into outlines

drowned in an underland of sleep.

What is the present’s analogue to archaeological recovery? Rishi Dastidar wittily consigns our consumerism to the causes of climate change: “A hobby of mine is collecting relics of the soon to be over age of oil. Or shopping, as it’s otherwise known.” Vince’s Legwork comprises collected relics of various sorts. The poems gathered here play with two definitions of the title word. Many of the poems, often constructed around the idea of a literal walk, journey into the past; many others, however, are about planning for the future – doing the necessary legwork to survive in a rapidly changing world. ‘Overpreparation’ points to both definitions:

the selection

of innumerable items to cover

all eventualities – except one, of course,

for these days the knees are a bit more

painful, the left hand perhaps is losing

grip, it’s hard going up hills, or vertiginous

flights of stairs.

The failure of preparation is a central idea in ‘Babel’, a well-crafted and often amusing poem that revivifies the biblical story of the failed attempt to build a tower to heaven. The dramatic monologue is a challenging form to pull off successfully because of the difficulty in capturing someone else’s voice in ways that are both credible and distinctly individualized. Vince is a master at this, as previous collections have shown. Here, in ‘Babel’, the point is clear: to humanize and valorize an act that the Old Testament renders as a faceless, arrogant ‘we’. In contrast, Vince supplies the voice of an individual builder revealing his own motive for participating in the project to build the Tower of Babel: ‘Our lives had voices,’ the speaker says. ‘We had one another to build on.’ Babel was an earlier age’s Voyager 1, a vain attempt to preserve a people’s voice in the face of annihilation.

The isolated voice typifies many of the poems in Legwork. I gather from this very full collection that Vince is an inveterate walker and traveller. Walking is often presented as a solitary activity, and many of the poems in the book are quiet and almost internalized portrayals of the Greek landscape that Vince has spent many years traversing. His three-part poem ‘John “Walking” Stewart’ is a panegyric to one of Britain’s most intrepid walkers, while his ‘Promenade Postcard’ wryly comments on the British habit of walking everywhere – and of filching a bit of the art or culture to bring back home. ‘Nevada Street’ is a particularly effective poem in its evocation of an unusual experience walking a familiar Greenwich street. At first, the poem feels strangely dreamlike: one day, all manner of things have appeared which weren’t there the day before – a grocer’s, a secondhand bookshop, an Underground station – and these new things look inexplicably old. Vince provides the prosaic explanation – that this familiar street has been transformed into a Blitz-era film set – and concludes the poem in a witty, extended simile: the unsettling experience ‘trailed behind / like a played-out dog with its chewed stick, / … / a cast-off scene from an old film, left to curl on the cutting-room floor.’

Once experience has been assigned to memory, what becomes of it? Is it more ‘real’ or ‘reel’? As any imaginative writer knows, other’s memories and experiences may prove more ‘real’ than one’s own. This is the sense I am left with after reading Vince’s stunning poem ‘Burning’. It begins with an error in judgement. Driving at night, the speaker is horrified to see a blaze on the horizon – but then it turns out to be merely the rising moon. That unreal experience causes the poet to recollect a story his father told (“real” to his father) of watching the Crystal Palace burn to the ground. ‘Thousands turned up,’ we are told, ‘for a closer look’, perhaps not so different (as he concludes the poem) from the ‘firemen [who] looked on but did nothing / as the synagogues flamed: Kristallnacht’. Intellectually, we are not so far from the doomsday voyeurs who populate Sastry’s collection: ‘a distant inferno would enchant your night’.

The overlays of past, present, and future, the melding of memory, reality, and dream are fine features of all these collections. Such layered visions are nothing more than what we can scramble to cling to in the face of inevitable collapse. Kieron Winn’s ‘The Last Walker’ (which creates a static charge with Vince’s walking poems) takes us on a night hike on Grasmere Common in the footsteps of Wordsworth; when the speaker switches off his headlamp and is plunged into a night free of light pollution, the scene is nothing short of miraculous as ‘a thousand stars came out at once’:

A staggered, glamorous, unrequiring throng.

They burn and blaze till bursting they disburse

Carbon and oxygen, the quick of life.

Winn describes this scene as not merely an unexpected beauty but as a vision of ‘the pure cool forces of the universe’. There is a clear sense of some ‘synaptic wit’ at work, much larger than human intelligence. Whatever it was, it remains undefined, but it leaves him with a momentary sense of assurance about the universe: ‘I gazed and felt no trace of deficit.’ Michael Vince’s ‘Misty Morning’ recounts a similar moment of philosophical profundity, as he encounters a strange and unsettling beauty in a fog that drapes his Aegean island, reducing all beauty to memory:

our accustomed view, has gone

under a pall of mist, a wide

deep immaterial mask above

what must now be the cleansed

island, sounds dampened down,

nothing to either see or hear

a few feet in front of us

while we stand motionless

rooted by this beauty, this white

veil that dampens our faces

Vince’s lines evoke more than what a mist-draped village or hillside might look like, reconstituted in the poet’s memory; his question is about the reality of past and future: ‘whether / we had really seen those things / properly before, and also whether / we would ever see them again’. Perhaps less inclined to a sense of wonder, and exhausted by imagining the inevitable doom, Tom Sastry understands the temptation not to think about the fact that ‘History – the flow of events we carry – / will soon carry us off.’ How pleasing it is simply to turn thought off: ‘It’s the magic of perspective. / There’s a dot, way down there. Inside it / empires set fire to themselves.’ What can we do, when disaster seems so remote yet so inexorable? In the poem’s most effective moment, we find that physical connection survives and is the only valid human response:

You squeeze my hand.

I turn for the emotion on your face.

Responding to that touch is absolutely essential. It allows us to enact Rishi Dastidar’s most vital habit of being: ‘A hobby of mine is existing.’