Kevin Gardner

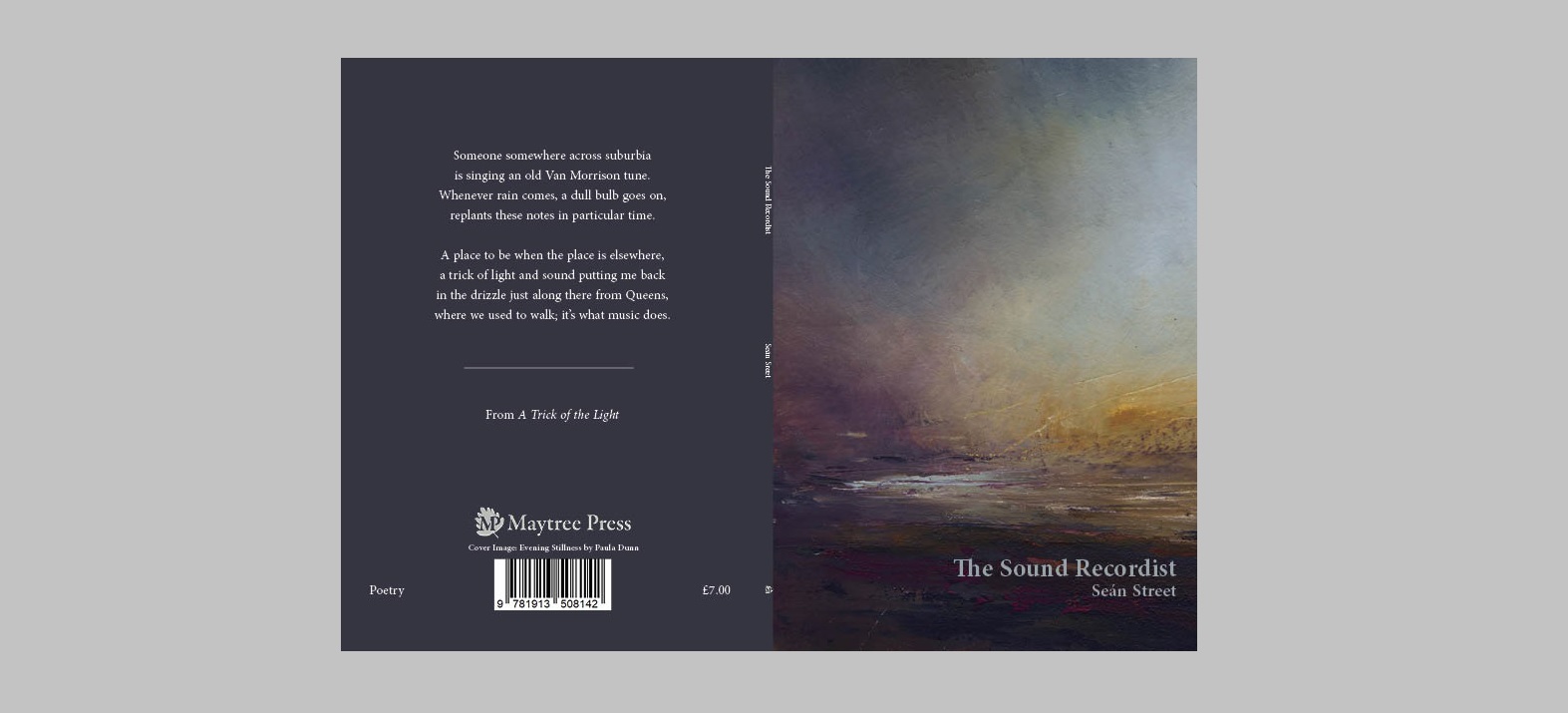

As Britain’s first professor of radio, Seán Street (emeritus professor at Bournemouth University) brings to the writing of poetry a unique perspective on sound. The author of six books on sound poetics, including Sound at the Edge of Perception and The Sound Inside the Silence, Street is a poet especially attuned to aural experience, and his latest collection, The Sound Recordist (his thirteenth), is perhaps more than ever a celebration of sound above all other sensory perceptions. As his title indicates, though, this collection is not merely about the experience of hearing; what intrigues the poet/broadcaster is the preservation of sound through both actual and approximate means – by way of recording technology or by way of language. The twenty-five poems in this pamphlet comprise a wide-ranging exploration of the human experience of sound: its endless variety, the triggering of memory, and the instinct to preserve.

The Sound Recordist is foremost a primer on the nature of hearing. The opening lines of ‘Early Show’ remind us that sound is at the very heart of all sensory experience, indeed that sound is a means for absorbing the visual and the tactile, ‘the edge of things / audible as the eye learns how to listen.’ Optic cues, though, are not just sound, but music – ‘Notes on dim staves’. Street does not abandon this paradox but demonstrates its truth with the example of fog. To most of us, fog limits what we can observe with our eyes; to a sound recordist, though, fog deadens another sense, ‘soundproofing the world – / turning things anechoic.’ When the sun burns fog away, the return of light brings the auditory coherence of music and poetry, of language restored. This idea resurfaces with a difference in ‘The Sound Recordist Goes to Town’:

But I hear most in foreign places when I’m drenched in the buoyancy of incomprehension, where language rivers flow best, not being understood.

Whether comprehensible or not, sound is a tactile experience. Synaesthesia is thus a useful tool in this poet’s kit: for instance, in ‘Listening with a Spider’, rain is a ‘warm straight sound’. Then there are the rugged aural effects of ‘Beyond Hilbre’: ‘a salt crusted face / carved to the cartography of weathers / like the gnarls and scabs of an old oak’s skin’. More even than tactile, though, sound is ‘electric,’ as he puts it in ‘Notes on Using the Studio’. Here silence itself becomes a vigorous form of sound: ‘Observe how your silence interrogates noise / and how your attention questions its decoration.’

Listening to silences can create meaning just as listening to sounds can. As Street puts it in ‘Listening to Miles Davis in the Cardiac Ward’, ‘silences / did not exist anywhere / until the sound framed their form’. In ‘Troglodyte’ (a poem which recalls Neil Moss, who died in a Derbyshire caving accident in 1959 and was buried in situ), the poet imagines listening to and recording the silences of the cave; however, he is not merely a passive sound recordist here. He reciprocates a ‘remembered acoustic’ by transmitting signals of his own. Sound is the means by which the poet can connect across time, with a spelunker lost more than seventy years ago, as well as with cave dwellers of ancient history. He echoes this concept in ‘Disused Airfield’, where sound seems only a memory, yet where ‘as it fades to distance it grows louder.’ This paradox is nearly inexpressible, he confesses: ‘To hear and know you’ve heard is sometimes enough. / An acknowledgement.’

The most extraordinary iteration of this idea appears in ‘Time and Light’, a brilliant meditation on the ruins of Holyrood Chapel – or of Daguerre’s painting of it. Street perceives Daguerre as a fellow traveller through a world of sound, one who ‘saw light impersonate sound’, one who shares the perception that the aural may be more real, as it were, than the visual. When the chapel fell to ruins, sound died: ‘voices that rang / flew out when unlocked acoustics turned dry.’ A greater loss (‘What died most’) were the echoes of worship. All that remains is broken light, ‘fragments of sky’. Yet in the imagination of the sound recordist-cum-poet, a litany of light remains: ‘What sings though is light, / sound has turned now to mysteries of light’, mysteries articulated across three extraordinary tercets that left me trembling in soundwaves of exceptional beauty. Elsewhere he may refer to this phenomenon as ‘a trick of light and sound’, but here is a genuine sense that light preserves lost sound.

Preserving sound, of course, is what the sound recordist does, but only Street could make poetry from the stuff of recording technology. In ‘Real to Reel’, the voice of a Suffolk yeoman is ‘eased from a tape’s turning cog, grain through a harvester’; the recorded oral history, played back, ‘ris[es] from dark silent spooling pages in new light’. Similarly, ‘Wild Track’, The Sound Recordist’s opening poem, finds in a type of audio recording a useful means of appreciating the process of creating poetry. Street reaches for understanding by testing a series of metaphors. What, after all, does poetry attempt to capture and preserve, but ‘The moment happening while / our back’s turned’? The blank paper staring back at the poet? That is transformed into the authorised freedom of ‘Perfect acoustic silence, / carte blanche.’ And the limitless possibilities of filling the ‘infinite page’ is the wild track’s ‘wide transparent space // beating wings on the air.’

The quest for meaning through sound is at the heart of this remarkable collection. Even the wildness of sound contains within it a metaphysical ambience, as in ‘Evensong’, where seemingly random elements of noise (blackbirds, a train whistle, a telephone) gather into a meditative liturgy. This is, as George Herbert put it, ‘something understood’, if not entirely known. Indeed, poetry is the most important sound of all, yet even it falls silent in the face of the unspeakable. ‘At the Grodzka Gate’ takes the reader from ‘the plain grey prose / of the everyday’ to ‘the unspeakable’ – the poem’s unspoken reference to the Holocaust. At the loss of words, the only meaningful gesture remaining is touch; yet as fingers brush together, a kind of sound is restored, ‘and you become words’. Though The Sound Recordist endows sound with metaphysical properties, here it is meaningful strictly for its simple, physical nature: ‘We walk, / the words that we are, / together a while, / handheld syllables.’ Such moments of silent sound hold the most potent meaning of all.