John Greening marks the centenary of the birth of George Mackay Brown (1921-1996), which falls this Sunday, 17th October.

The June bee

Bumps in the pane with a heavy bag of plunder

‘I first got to know George Mackay Brown’s work in 1982 when we were living in North East Scotland, teaching refugees from Vietnam. Arbroath didn’t feel so very far from Stromness, and these poems of beach and cliff-edge, of fishing communities and rural customs enchanted me. They also chimed with some of the Chinese lyrics I was reading: Li Po, Tu Fu – intensely human voices often from remote outposts…’

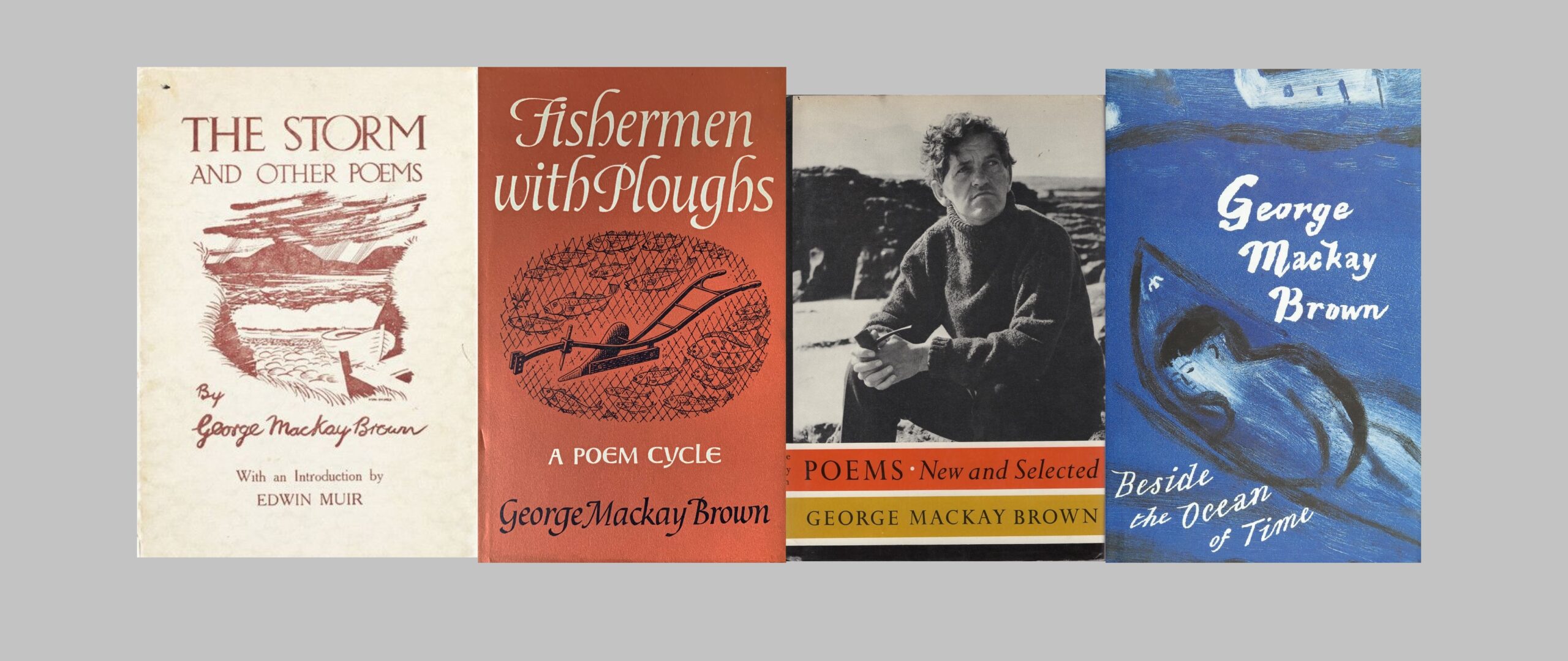

At least, that’s how I had been going to begin this piece when I settled to write it just as lockdown was ending last June. But apart from the fact that the Orkney poet would hardly have considered his home remote from anywhere, I began to suspect that I was mythologising my own past, making off with ‘a heavy bag of [literary] plunder’. No, I must already have discovered George Mackay Brown by the early eighties. All those hours listening to (and working at) BBC Radio 3 would surely have alerted me to the tripartite unhyphenated name because of its regular association with another: Peter Maxwell Davies. Even now, I can’t think of any more perfect collaboration between poet and composer since Franz Schubert set Wilhelm Müller. But whereas much of Max’s music is forbidding and requires an effort to enjoy, Brown’s is as instantly appealing as a Schubert song. Fishermen with Ploughs (published in 1971, shortly after the two men met) is the book that I fell in love with. I still have the 1979 reprint, which suggests it was around that time I read it.

Certainly George Mackay Brown’s poetry would have been a refreshing change from some of the bleaker Modernists I had been exploring after university. He doesn’t obviously emerge from the tradition of English Literature as do his fellow Orcadian Edwin Muir and Lewisman Iain Crichton Smith – Gaelic writer though ICS was; nor is he one of those wha hae stood proudly with Hugh MacDiarmid. He seems to owe more to the sagas and the Edda (in which I was steeped at the time), and to the ritual texts of the Catholic church (in which I wasn’t). Yet if I was reading him the year we set out for our two years in Upper Egypt, I must have seen what he had in common with the Imagists who were a great influence on me; and it strikes me now that Brown’s poetry probably fed into my own early Egyptian poems much more than I have admitted. The exquisite observations of, say, ‘Beachcomber’ or ‘A Child’s Calendar’ are like fragments from a tomb painting. This is a poet who looks hard at everyday life but is open to the possibilities of the world beyond.

What else attracted me to that collection? Apart from being impressed by his skill with the short poem, with his use of a self-contained runic stanza (often seasons, months of the year, days of the week), there was the sheer ambition of such a book-length sequence, ‘a poem cycle’. I remember being excited by its ingenious allegory, allusions to nuclear holocaust behind something timeless, almost heraldic. I was drawn, surely, to the unusual combination of spiritual reach and humour, as well as recognising the poet’s extraordinary gift for characterisation in miniature.

George Mackay Brown is a local poet par excellence, who knows how to make what Tomas Tranströmer called ‘a song about what is near’ without sounding parochial. Undoubtedly he helped me see the virtues in paying close attention to my home patch, and I think I carried some of that with me when we left Scotland in 1983 and settled in Huntingdonshire, which is about as different from Orkney as you can imagine. By coincidence, friends we met here actually came from the islands and had known George personally, so I heard quite a few stories about him and the many visits he had from an increasingly pushy band of international fans. Later I would chat about him with other poets: the Americans John Haines and Dana Gioia, my Kimbolton friend Stuart Henson, and particularly with Dennis O’Driscoll (whose exchange of letters with him should be published). I never met him myself, nor have Jane and I yet made it to the Orkneys, though when I was at Hawthornden Writers Retreat in 2010 I took the bus to Newbattle Abbey and walked in the grounds imagining those conversations between the tyro poet and the warden, Edwin Muir.

There are some poets whose discovery marks a turning point, whose biography when it arrives (there have been two at least of GMB) feels like an event. They are writers whose work you want to read in its entirety, and I have read many of the plays, short stories, novels, pieces of local journalism as well as all the available poems. Perhaps you could point to a lack of variety, accuse George Mackay Brown of saying the same thing in the same way over and over again. But as a reader, that hardly matters, indeed it’s precisely what you’re so devoted to. If you have found a voice like no one else’s, you just want to listen to it.