Kevin Gardner

Three new and seemingly distinct collections by Rishi Dastidar, Jane Draycott, and Ruth Padel join their voices in opposing the kind of exceptionalism that deludes nations and their leaders to the climate crisis and their own impending ruin, that continues to convince some that Britain was chosen to rule the waves. British exceptionalism was of course formed in an awareness of its coastal uniqueness. Though John of Gaunt’s lines, “This precious stone set in the silver sea, / … Against the envy of less happier lands”, still echo, today the words ring out more with nostalgia or hollow irony. Such visions lead to certain destruction, by underscoring national crises from climate-change denial to post-Brexit economic chaos. Even Gaunt got this much right, seeing a kingdom “bound in with the triumphant sea … bound in with shame.”

*

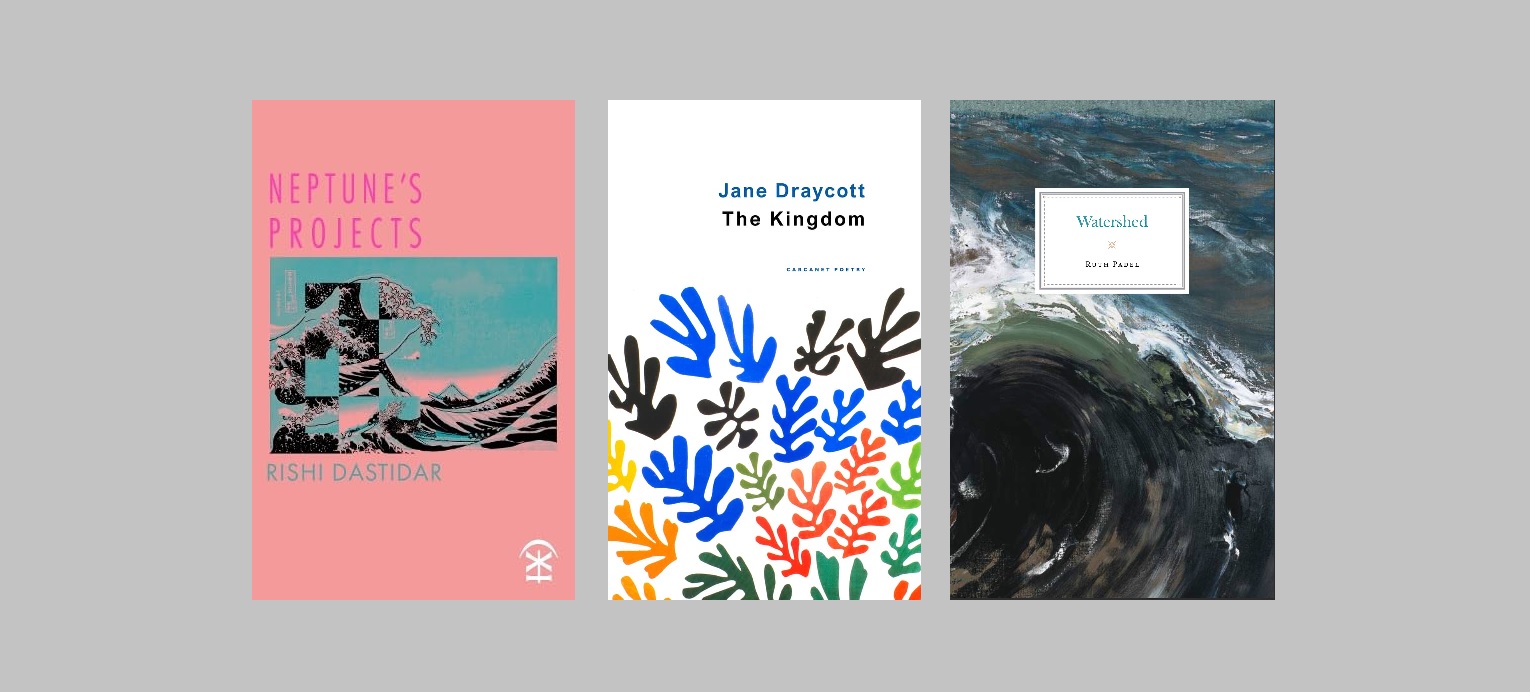

Rishi Dastidar is a master of a sort of persona poetry uniquely his own, and that skill is showcased in Neptune’s Projects (Nine Arches, 2023), a collection of poems about the sea, many in the voice of Neptune himself. This is a natural successor to his previous book, Saffron Jack (Nine Arches, 2020). Where Jack had meditated on borders and the idea of a retreat from the turmoil and brutality of the political and social climate into an imagined micro-kingdom of his own, Neptune explores the shifting border between land and sea as icecaps melt, coastlines shrink, and the ocean reclaims coastal boundaries. Neptune’s moods shift as often as the character of the sea itself, and serious subjects are rendered in the playful and sardonic voice we expect from a Rishi Dastidar collection.

This Neptune is not the mighty Poseidon of classical myth; rather, his power is circumscribed, and he suffers from old age and world-weariness. His strength is purely rhetorical; Gaunt-like in his eloquence and wit, he voices humanity’s incapacity to respond effectively to crisis. He knows that his divinity no longer impresses anyone: “once I had power. People worshipped me”, but today he is reduced to a professional sports mascot, as we see in ‘Solaris, a sequel’:

Trouble is – I despair too. I am not mighty, I am overwhelmed; turns out that I needed something – land, any land, more land than this – to define myself against. My force needed limits to extend its range, to shape it into something useful. And there is not enough of it to mean something to me. Instead, I sit here, drifting, waiting for the next match to begin.

A playful side trip to an art gallery gives us several fascinating ekphrastic poems encouraging us to think not only about how artists have represented the sea but also about how our mythmaking may have blinded us to our own power over the environment. The human arrogance driving that power comes of course with colossal risks, and Neptune seems to delight in the sinking of human dreams:

Console yourself as you drift down past

the seahorse paddocks into secret seas.

The shipwreck champagne is sweeter here

and won’t give you the bends.

Humanity’s titanic ego is cause for a “Pretanic” interlude (Dastidar’s first collection, Ticker-tape, also contained a “Pretanic” sequence). Here the focus is more narrowly on what used to be called the British Isles, for which Neptune has an unsurprising skepticism, given the associations between Britain’s coastal geography and nationalism:

its inlets and nooks, bays and shores, holding

and holding its lungs shut until whoosh!

national pride expands, flags blare, trumpets

billow and nostalgia goes on the march again.

This island nation somehow thinks itself secure not only from Neptune’s wrath but also from a climate crisis that the rest of Europe seems willing to address, a nation (“sorry, a decisive / majority of us”) that has determined “that nostalgia is the best form / of statecraft to respond to a / future of heatproof algorithms”. Ripostes to British exceptionalism course through the Pretanic sequence: “You can’t be / weaned off glory, you know”; “too much past leaves us in a stupor”. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Neptune returns at the end with more urgency and anger – “not wine dark but angry whisky living boiling”.

If the British are drawn instinctively to the past, let it be the remotest part of the past, reversing evolution with a return to the saltwater from which all life emerged; if drowning results, so be it. As Dastidar’s Neptune impassively observes in the prose-poem ‘Wetware’: “We were together once, we were the same once, and a fix is simple immersion. Give yourself up to the past you emerged from.” Ultimately, Neptune cares deeply for humanity: “Waves forgive,” he chants. Nevertheless, he is incapable of halting our pell-mell race to self-destruction. Neptune’s Projects is a brilliant rejoinder to this doomed course.

*

The title of Jane Draycott’s latest collection, The Kingdom (Carcanet, 2023), would seem to suggest a world of certainty and stability, perhaps Gaunt’s “sceptered isle” or “teeming womb of royal kings”. Instead, though, we find mutability and impermanence, and time and space have become unfixed. In the title poem, the linguistic fabric is interwoven with silk threads of medievalism – “I was thirsty / languissyng in the doorway / behind the post office” – and its setting weaves other-worldliness into the unnamed kingdom:

I was a stranger

turned half to stone

seeking releyf in severe weather

coming hyther in search of something

oute of thys madnesse

something to inherit.

The result is a dream vision – perhaps not entirely unexpected from the translator of Pearl.

Although most of her poems eschew such direct medievalism, they are eerily dreamlike, with an alluring quality that invites return visits to this kingdom. One should expect shadows and faint light, a nighttime restlessness in ruined cities, ominous though without menace, a place with “strange furious birds like feathered machines / raining stones on our chambered turbulent dreams”. Despite uncertainties and even fears, her poems are rife with vital securities – tenderness, love, and hope. ‘In the Bones of the Disused Gasometer,’ for instance, begins aphoristically and without irony: “A ruin’s a fine thing to swim in.” Here in this urban ruin, with its “black wet dog at your heels” and “the gas-dragon / caged out the back”, hope blossoms with emblems of rebirth and beauty:

the pipework’s

been salvaged, reborn as a deep-toning chime

at the opera house …

continuing life as a nightly-struck bell,

the derelict stars pouring down

through the holes in the sail of the sky.

Is Draycott’s kingdom a metaphorical England? Her capacity to re-strange the ordinary makes such easy equations tricky, but there’s no doubt that a layer of Englishness has been embedded. In ‘The Claim’, her kingdom is El Dorado, the fabled city of gold – or “all that remained” of it. However, it no doubt alludes as much to London as any other once-magnificent imperial capital, its spirit “split into a dozen pieces / like a priceless vase exploded / on a marble floor, slipped / from the aristocrat’s hands”, an image that calls to mind the post-imperial ruins of Britain, its faded grandeur, power, and glory.

In this kingdom, though, broken things can be “repaired / with shining seams of precious metal, / … / and even made more lovely / by the gleaming scars”. However, since such repairs require “sufficient gold”, we are invited to contemplate whether they are worth undertaking. An alternative is, as Draycott imagines, to permit nature to reclaim the ruins, “like honeysuckle over a broken wall”. From post-imperial ruins rise other, metaphorical kingdoms:

the kingdoms of the red and blue

and of the yellow with its scattered envoys

everywhere – the trampled primrose,

brimstone in the early butterfly, the orpiment

in ancient glass.

The poems of The Kingdom are beautifully and intricately wrought, like an Elizabethan knot-garden, from which metaphor any lingering sense of a political kingdom is translated into a natural one. Thus in ‘My Ticket’, she first imagines her heart, like that of Richard the Lionheart or Elinor of Castile, “floating like a baby in the finest brandy inside its crystal casket”; subsequently, the empty cavity of her chest “is filled with flowers and salts and spices”. Despite the image of death and embalming here, overall the collection brims with life and rebirth.

The Kingdom closes with an extraordinarily beautiful and hopeful benediction, “The Experiment.” In this kingdom, cynicism may prevail: “In a small country like ours you must be prepared / for no-one to think this possible,” and “this” seems to refer to any experiment in hope and wonder, which she illustrates with an allusion to the Wright brothers’ “dazzling feats and equilibrium”. The poem ends with a striking image of the mind’s capacity to recollect beauty and an unexpected didacticism that few poets can get away with – a commandment to forge human bonds, a key perhaps to the kingdom: “Only the light remains / and the roses wild and idle just as you will remember them. / Stay together whenever the times allow”.

*

As if in response to both Jane Draycott and Rishi Dastidar, Ruth Padel writes of the mysteries “sluicing from the underworld / to the concrete Thames Barrier”. The kingdoms of earth and sea we have just encountered collide in Padel’s chapbook, Watershed (Hazel Press, 2023). Water in almost every conceivable capacity – rains, rivers, lakes, oceans, rising waters, poisoned waters, flash floods, water deities, monsters of the deep, Swan Lake, water on the brain – is here. The flow of water, sacred and life-giving, is “like a love you never noticed”.

Many of the poems are responses to climate change, and these carry an understandable urgency:

all the women of Shrewsbury

standing in their living-rooms

wearing boots and quilted anoraks

watching kettles

float into the street.

Despite the rhetorical force and the cogency of her implied arguments, the emotional impact stems as much from the beauty of Padel’s language and her commitment to art in the face of crisis:

we can stand above the loch

catch the flicker of a burn

reflecting emerald sky-foam

from Aurora Borealis.

In Watershed, there is even room for humour. One poem recollects a rollicking performance of a children’s church play about Noah’s Flood; another thinks of a water-closet as “the one truly fortified space / where a poet can prepare a reading undisturbed”. A third, pushing the limits of water’s metaphorical flow, thinks of the “world walloping about like a flooded carburettor”.

Such humour is an antidote – if not to the poison in our waters, then to our sense of helplessness as we face these crises. Like Dastidar’s Neptune, there is little we can do but look on in horror at –

… the last

struggles of the water butterfly in toxic red mud

all that is left of our river

when they have extracted the aluminium

connecting the world to your SIM card.

Yet Padel resists despair by embracing the creative expression of beauty. Her own voice is like that of Marian Anderson, whom she imagines singing ‘Deep River’, her voice “the sparkle of rain watering the earth / and the journey this drop from my tap has taken to get here”.

Underneath the beauty remains an urgent reminder that beauty is illusory. ‘Lady of the Lake’ reimagines one of Britain’s most powerful myths in a setting of environmental horror; its affective power rests in its transformation of an atoll of microplastics, like an oil-slick rainbow:

smothered the whole surface in froth

islands and pinnacles

shredding away from their own crests

glimmering like net-trim on a ball-gown

gossamer breaking to quicksilver.

Can a poet do more than construct beauty out of the nightmares of pollution, climate change, and political loggerheads?