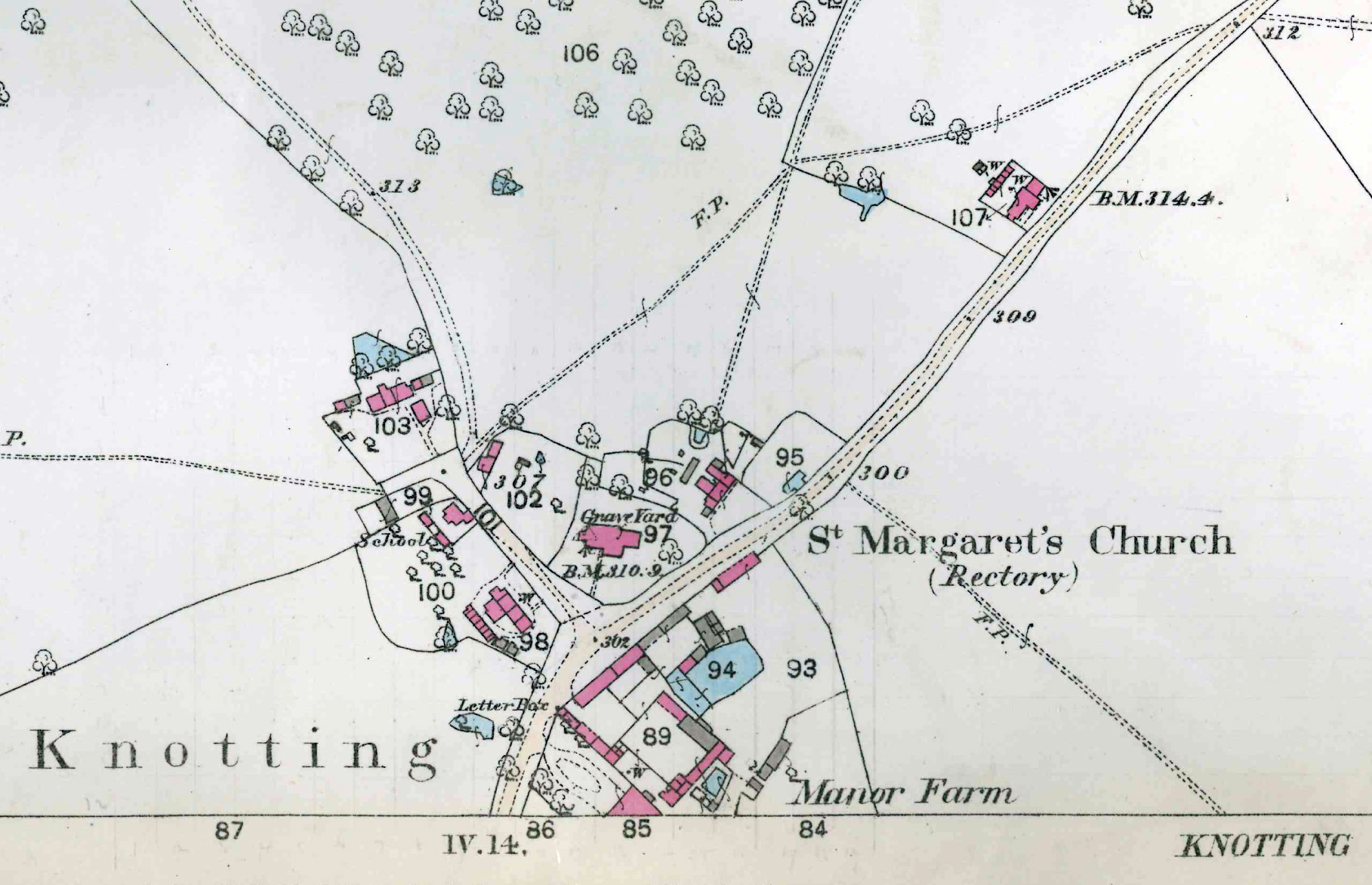

The main part of Knotting in 1884. Courtesy of the Bedfordshire County Archives.

John Greening

It’s unlikely that many readers will remember the original elegant editions of these two collections by Martin Booth (1944-2004). The Knotting Sequence (1977) and The Cnot Dialogues (1981) appeared from The Elizabeth Press in the USA and, as Tony Frazer explains in a very interesting Publisher’s Note, “received minimal distribution” before the press itself closed. I am lucky enough to possess one of those five hundred original copies of the first book, printed “on Magnani rag paper”, complete with a publicity insert quoting a review by Roger Garfitt describing the poetry as “rooted in history and in the galactic dimension”. The same flyer tells us that “Mr Booth has served as Schoolmaster Fellow of St Peter’s College, Oxford, and is currently the Poetry Critic of the Tribune” but also, intriguingly, that he is “County Area Archaeological Correspondent”. Shearsman’s new edition adds “screenwriter” (for BBC wildlife programmes), but more importantly it reminds us he was a significant novelist.

During the decades after these poems appeared he wrote his highly acclaimed works of fiction, including Hiroshima Joe (Booth was brought up in Hong Kong and shared with Tony Frazer an interest in the Far East). This novel enabled him to give up teaching, but would have drawn an even wider readership had it not been eclipsed by J.G.Ballard’s Empire of the Sun, which was Booker-shortlisted and then made into a film (Booth’s Industry of Souls was in fact also shortlisted in 1998). There would be more novels and some distinguished non-fiction too, though the topics were very much of their time – a history of opium, Aleister Crowley, the “alternative” Arthur Conan Doyle and Jim Corbett, tiger hunter-cum-conservationist. But when these early poems were composed, Martin Booth was (like so many in the era before Creative Writing departments) a schoolmaster-poet. He had received an Eric Gregory Award, appeared on George Macbeth’s BBC poetry programmes, and been encouraged by another Eastern enthusiast, Edmund Blunden, but he could not persuade a major poetry publisher to take him on.

At the end of the ’sixties, Booth set up the Sceptre Press in the tiny Bedfordshire hamlet of Knotting, not far from where I lived during my own years as a teacher. It is a place I still delight in cycling to since it has a very special atmosphere, much as it obviously did in the 1970s. The yellowing flyer in my American book explains that Knotting had a population of 27 before the poet’s son was born (historically it has been somewhat over-endowed with poets – the manor belonged to both Edmund Waller and the Laureate Henry Pye) and it is no busier in 2020. According to Booth’s British Poetry 1964-84: Driving Through the Barricades, the Sceptre Press of Knotting published ‘over 400 booklets, broadsheets and books in thirteen years’ (although its archive suggests longer, from 1969-1974). It was highly regarded and the back catalogue is impressive, including names such as Ted Hughes, Sylvia Plath, Seamus Heaney. Frazer implies in his Note, however, that by the time the Press closed and the Knotting poems were written Booth knew that as a poet himself “he was not going to achieve a breakthrough with a major British poetry press”.

These two sequences are inseparable from the place in which they were written (another good reason to visit it) and they constitute a good deal more than local history in verse. They are nevertheless particularly evocative of this rather overlooked part of England – or how it was when there were still elms and peewits:

a row of dying elms the crack of frost the cry of lapwings

It is as if the very sparseness of the verse – learnt, perhaps, from the kind of American poets The Elizabeth Press tended to favour – lets our notorious wind from the Urals into the language. It’s certainly fitting for a landscape soon to be shorn of those elms and hedgerows. Some will no doubt dismiss the poems as the unacknowledged offspring of Offa and Crow (“in the forest/Cnot tried/screams’), but Booth’s long thin verses have their own personality, and are very evocative of a certain kind of vulnerable landscape (barking muntjacs, peregrine and Little Owl) featuring a haiku-like delicacy which is not in Hughes or Hill, though may be found in Penelope Shuttle or Frances Horovitz (both of whom had Sceptre pamphlets):

November, Here mist at dawn: damp hair and cobwebs love of the sun now the Fiat won’t start who cares that sings?

Sometimes the line-breaks seem to be all that is keeping the poems from prose – and Booth’s critics will see in this a foreshadowing of his later decision to turn to the novel – but they are not prose. There is a powerful music embedded here, one that Eastern poets might recognise, as when he writes of Knotting church:

under the centre beam, Bunyan sang

The sound of “under” is echoed by “centre”, and “beam” bumps satisfyingly against “Bunyan”, setting up that solitary monosyllable, “sang”. As Booth’s lines teeter on the edge, they sing indeed: a harsh song that has not dated any more than Bob Dylan’s.

There is little to distinguish the 1977 and 1981 sequences and they make a natural pairing, though an especial relish pervades the earlier book, a varied series of tussles between ancient and modern, the poet complaining about Anglo-Saxon roads (“it is/all your/fault that/the lane/twists”), Cnot biting back about “bad shooting”. There is affection, however; a gushing letter from New York prompts a blokish quip, “now tell/me you’ve/met/god”. But it’s Cnot the farmer who always seems to be winning, the genius loci who doesn’t care if the Electricity Board have erected “a grey/relay transmitter/box” in the poet’s eyeline – he has seen entire naves come and go, after all, saying each time “we don’t/really need/this holy/building”. By the end of the first sequence, Cnot is hardly mentioned: yet he’s in that “we” as the poet sits on a plane above Salzburg dreaming “of the ash/we planted/seven days/ago”. When he reappears in The Cnot Dialogues, the exchanges resume with much the same vigour and wit, although this time there is Booth’s son, Alexander, to address too: “listen, you/small, shagged-/out piece of/flesh called a new-/born son//do all/I say and/you’ll not go/wrong.”

Martin Booth’s sequences deserve to be reissued on this side of the Atlantic and to be read more widely (and a little more locally) at last. The Shearsman Library edition (Volume 12 in Tony Frazer’s invaluable series) is itself beautifully designed with plenty of space for the poems, decent paper, and a 1646 colour map of the area on the cover.

Martin Booth’s The Knotting Poems is available from Shearsman here.