Rick de Villiers

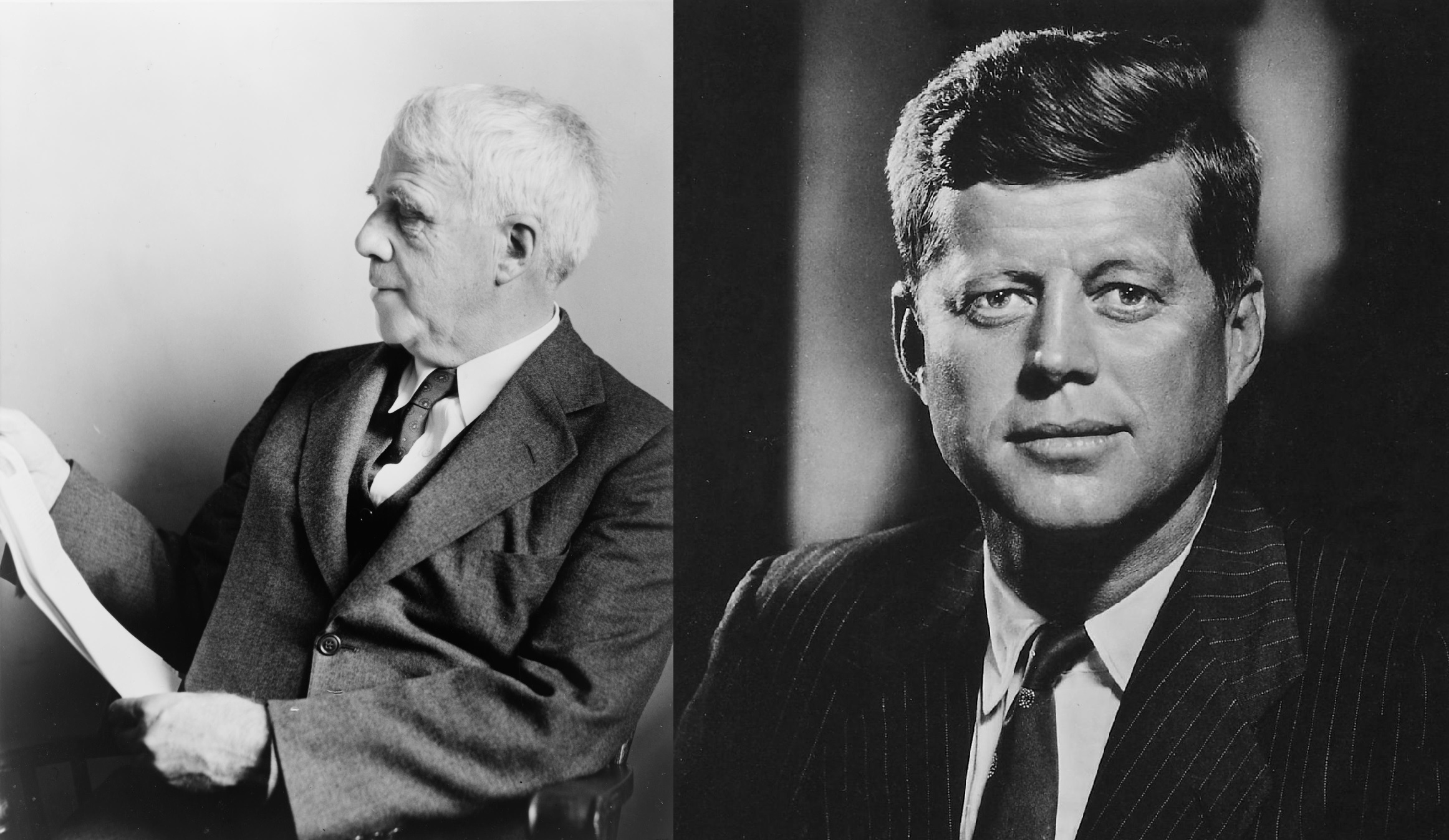

The sun shines on nothing new, saith the Preacher (and Samuel Beckett after him). But what if, on 21 January 1961, it hadn’t? What if neither snowy glare nor a whipping “Nor’easter” prevented Robert Frost from reading ‘Dedication’, the poem he’d written specially for the inauguration of John F. Kennedy? If that poem had seen the light of day – without casting so much of it back into the eyes of the 86-year-old poet – would the American tradition of inaugural poetry look any different?

It’s been just over two months since Amanda Gorman’s performance of ‘The Hill We Climb’. The Internet is still in recovery. Since then, Gorman has gone on to grace the Superbowl, sign a modelling contract, and top the Amazon sales chart. Her inauguration poem already has dedicated pages on Litcharts and Gradesaver. Its viral success is undoubtedly due to Gorman’s delivery: poised, daring, dazzling. But another reason for this success is the poem’s consolidation of all that makes for good occasional verse about new beginnings.

The tradition of American inaugural poetry is neither old, nor long, nor bipartisan: six poems in total, spread unevenly across seven decades, all allied with Democratic victories. So it’s not surprising that these poems have much in common. There’s the capaciousness of address, pronouns to absorb us all. ‘We encounter each other in words,’ as Elizabeth Alexander has it. Then there are the appeals to our nobler instincts, our best selves: ‘only a little lower than / The angels’ (Maya Angelou); ‘All of us vital as the one light’ (Richard Blanco); ‘If we merge mercy with might…then love becomes our legacy’ (Gorman). And though history tugs at it like a dark crime, the triumphant inaugural poem is always subtended by the curve of optimism. Gorman glimpses the dawn even amid ‘never-ending shade’; Miller Williams’s ‘Of History and Hope’ bends, despite deep misgivings, towards a promised land.

These features – the inclusive address, the moral uplift, the expectant tone – all subserve the signal attribute of the apt inaugural poem: absence of ambiguity. Emotive hooks should be obvious, the spur of hope direct. The people shouldn’t have to look hard to find their likeness, to find themselves enlarged by the miniature. In poetry of this kind, oratorical and oracular, cliché has its place. The well-worn metaphor, the expected rhyme, the smooth-trodden phrase – these aren’t a cop-out; they’re common currency. And it’s this currency that extends the curtesy of ready comprehension. Fitting irony, then, that Robert Frost struggled to puzzle out the inaugural poem that was itself never to be inaugurated.

To crown the narrowest of electoral victories, Kennedy invited Frost to participate in the inauguration. Frost was honoured but anxious. There wasn’t enough time to write something specially for the occasion, nor was he sold on the president-elect’s suggestion to tweak the ‘The Gift Outright’. Partial to the lesser travelled road, Frost eventually launched into a new work just weeks before the ‘august occasion’. The couplets didn’t come easy, and Frost was still tinkering away hours before the event. Last-minute drafting meant he couldn’t commit the poem to memory, so he had it printed out in large type to ease reading. Stood on the East Portico of the Capitol, the old laureate made a stuttering start. The light was too sharp, his eyes too weak. After botching the first three lines, he lapses into feeble paraphrase: ‘It’s about…the order of the ages…’. JFK cringes in smiling encouragement, Jackie Kennedy casts around her, bemused. But then Frost finds his voice and recites from memory ‘The Gift Outright’. In the space of a minute, he goes from tattered coat on a stick to monument of magnificence.

How different things might have been had ‘Dedication’ been read. What makes the poem remarkable is its awkwardness. Not the clumsy delivery, though there’s a proper impropriety about that. Awkwardness, rather, about poetry’s alignment with power, despite the avowed rightness of fit. Take the opening three lines, the ones Frost had managed to read:

Summoning artists to participate In the august occasions of the state Seems something artists ought to celebrate.

‘Summoning’ conjures compulsion, the stressed first syllable the voice of command. The hint of soft coercion is caught also in ‘ought’. By all accounts (says this word), going on appearances, the concurrence of art and politics is something to be welcomed. But the triplet rhyme is a little insistent, a little keen. This coming-together only ‘seems’ something to cheer.

The title, too, withholds. On its own, the word ‘dedication’ goes nearly far enough to convey what the context demands: a tribute to triumph. But by stopping short of gifting this link outright, ‘Dedication’ declines total commitment. It throws us back onto the poem as poetry, labelling itself generically. Generic, because no narrower detail is given: not ‘Dedication for JFK’, not ‘Dedication to Power’, not ‘Dedication on 21 January, 1961’. By avoiding the prepositional transfer that would release the abstract into the particular, ‘dedication’ stands oddly aloof. The poem is generic in a second sense: it situates itself in a tradition of dedicatory verse where power and poetry meet.

This verse that in acknowledgement I bring Goes back to the beginning of the end Of what had been for centuries the trend; A turning point in modern history.

These lines would have mystified the crowd had Frost got that far. Even when read slowly and repeatedly, they resist simple paraphrase. Is this the kindling of a forgotten practice, the resuscitation of a glorious past? But then ‘trend’ is so given to quick endings, so easily buried with passing tastes. Perhaps we should hear the faintest of clicks, Pandora’s box reopened: this poem, the double tongue says, harks back to a moment when poetry lost its autonomy, a moment we might call the ‘beginning of the end’.

These halting, tonally uncertain lines then open onto a patchy story of America’s past. The origins account is another recognisable trope of inaugural poetry. But unlike the animist connections in Angelou’s ‘On the Pulse of the Morning’ or the cosmopolitan networks in Blanco’s ‘One Today’, ‘Dedication’ likes to dwell in a zone of indeterminacy. The poem shifts between the general and the specific, between quasi-philosophical questions and scraps of a known national history. It muses on the spirit of democracy and its incarnation among decolonising states. It nods to American technological advancement, its neo-imperial sprawl. None of this is straightforwardly celebratory. If it seems naïve, condescending, and downright denigrating to speak of ‘races swarm[ing]’ after the model of American liberty, these blights have a splash-back effect. The poem undoes its central theme by exposing, despite best intentions, the chaos beneath. Democracy, the poet owns, is

…a confusion [that] was ours to start So in it have to take courageous part. No one of honest feeling would approve A ruler who pretended not to love A turbulence he had the better of. Everyone knows the glory of the twain Who gave America the aeroplane To ride the whirlwind and the hurricane.

No image better captures the poem’s swerves than this aeroplane, gleefully crashing through storms of its own making. One minute the cabin pressure is stable, the drinks tray level. We hear the soothing voice of the captain telling us we’re on schedule, though we sense he’s reading from a script. The next, some deranged passenger seems to have seized the PA. Don’t you pretend, he says, that you’re not in love with danger, not a little thrilled when the mortal engines roar. But then – breaking through the bluster and bravado, rising above the clouds – there’s a moment of quiet pathos:

Some poor fool has been saying in his heart Glory is out of date in life and art.

These seem to me the quintessential Frostian lines in the poem. Across his work, his deepest sympathies are reserved for the humble of the earth. His most trenchant mode is honest confusion, the refusal of a straightforward answer. W. H. Auden once wrote that Frost’s style was unsuited for public occasions exactly because of the ruminating voice that seems to converse with itself. However briefly, that conversation is overheard here. We don’t have to squint to see the poet as the ‘poor fool’ who feels uncertain about glory. Nor is it hard to see the poem’s subsequent ‘glories’ – of ‘the next Augustan age’, of ‘poetry and power’ – hollowed out by this uncertainty.

Most people would agree that the sun’s unbearable brightness on 21 Jan, 1961, was a saving grace. It spared Frost’s blushes by preventing him from reading what is undeniably a bad poem. ‘Dedication’ lacks everything that defines his best work: a sense of drama, the unassuming yet incisive narrative voice, the poignancy of the ordinary. In a recent podcast, the poet Mark Ford called ‘Dedication’ ‘a long lame poem in couplets, which no one wanted to hear’. Least of all the new president. For if Frost’s stammerings ultimately helped him save face, a fluent reading might have embarrassed Kennedy. For good or ill, a fluent reading might also have shaped a different inaugural tradition.